UPDATE: May 30, 2025: The Southern Education Foundation's Equity Assistance Center program grant has been temporarily reinstated by the U.S. Department of Education in accordance with a May 21 court order as the organization's lawsuit against the federal agency moves forward. The grant, one of four in the Equity Assistance Center program, covers public school districts in 11 Southern states. "In view of the history of race in America and the mission of SEF since the Civil War, the audacity of terminating its grants based on 'DEI' concerns is truly breathtaking," U.S. District Court Judge Paul Friedman wrote in the opinion for the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

______________________

The Trump administration has in recent weeks worked to undo key education civil rights efforts dating back to desegregation that were meant to provide educational equity for students of color, and especially Black students.

The White House fiscal year 2026 budget proposal released this month shows the Trump administration is pushing to completely eliminate Equity Assistance Centers. The proposal claimed the centers have "indoctrinated children" and that their closure would "restore merit-based practices at school" while ensuring "districts do not have to implement weaponized, woke policies."

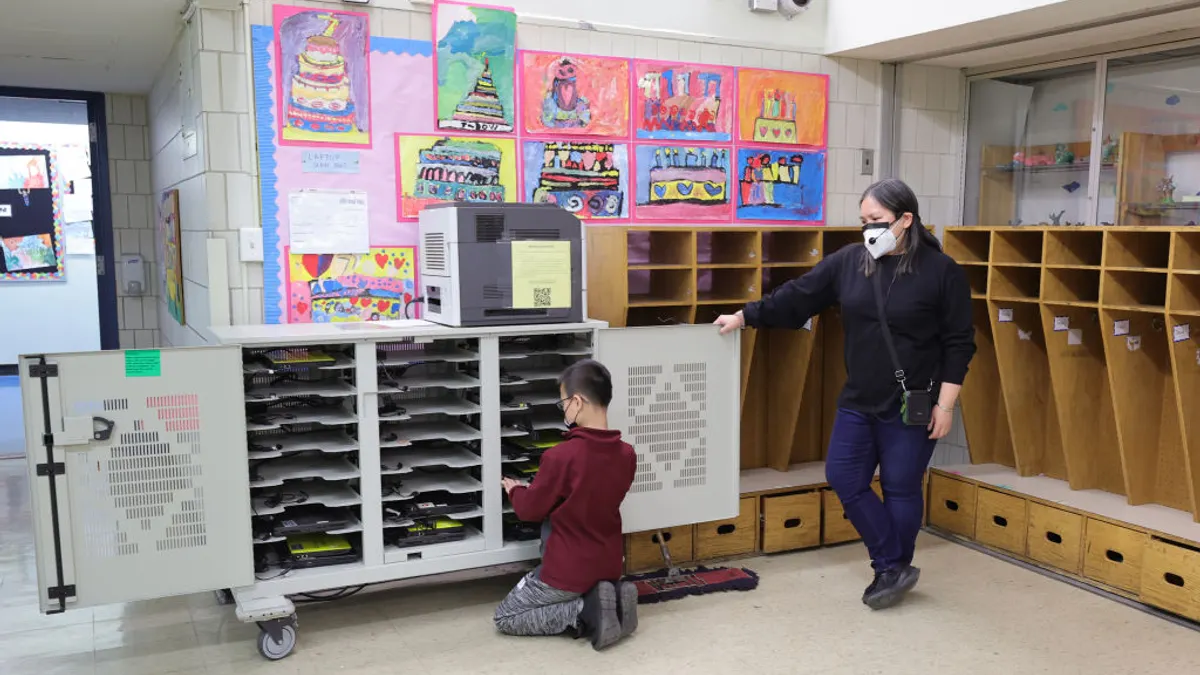

Equity Assistance Centers were established under the Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and originally called Desegregation Assistance Centers. They provide technical assistance and training to schools, districts and school boards to "address education issues occasioned by school desegregation," such as harassment, bullying and prejudice, according to the U.S. Department of Education website. The centers also help districts interpret data to identify disparities and to address those disparities through efforts like professional development for teachers.

President Donald Trump’s proposed budget would eliminate $7 million in funding for the centers, slashing the nation's oldest education technical assistance program entirely.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People filed one of at least two lawsuits challenging the administration’s decision to shutter EACs nationwide. According to the NAACP and Legal Defense Fund, which filed its lawsuit May 9, the administration already closed all four centers nationwide on Feb. 13, months prior to the budget proposal that would eliminate the program’s funding.

The move would "roll back decades of progress towards civil rights and equal opportunity in public education," Katrina Feldkamp, LDF assistance counsel, said in a statement after NAACP filed its lawsuit.

The Southern Education Foundation, which filed its own lawsuit on April 9 challenging the administration's closure of the Southern EAC office, said the offices provided online workshops to help schools tackle issues such as teacher shortages, lack of education resources and school-family engagement, among other activities.

“Eliminating the Desegregation Center is a direct attack on legal protections gained through the Civil Rights Movement,” said SEF President and CEO Raymond Pierce in a statement following the organization's lawsuit filing in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

SEF operated the EAC-South office before its closure on Feb. 13. According to the organization, 132 school districts across the nation — 130 of which are in the South — remain under federal desegregation orders that the EACs helped address.

However, late last month, the Department of Justice walked back one such desegregation order for Louisiana's Plaquemines Parish School Board, which was issued after the U.S. sued the board in 1966. Assistant Attorney General Harmeet K. Dhillon said lifting the desegregation order was "correcting wrongs from the past," as the school district had to "devote precious local resources over an integration issue that ended two generations ago."

While desegregation efforts peaked in the 1980s, segregation resurged after 1988, and national data shows schools are generally more segregated now than in the early 1990s.

Administration undoes other tools related to achieving equity

The Equity Assistance Centers closed by the administration were one of many tools used by the Education Department's Office for Civil Rights to ensure Black students, and students of color more generally, have equitable access to education.

In recent months, the administration and OCR have taken additional efforts to roll back civil rights advancements that were meant to address the longstanding impact of slavery and racism on Black students. This rollback is part of a broader attack on diversity, equity and inclusion programs that it calls "divisive" and "discriminatory."

On April 23, for instance, Trump signed an executive order "to eliminate the use of disparate-impact liability in all contexts to the maximum degree possible."

"Disparate impact" is a term used to describe the disproportionate and often unintentional impact of seemingly innocuous policies on traditionally marginalized students. Disparate impact investigations launched by OCR under past administrations were systemic racial discrimination reviews of school districts' practices and policies in areas such as student discipline. The practice was originally reversed under the first Trump administration and then revived under the Biden administration.

The executive order, however, said that disparate impact theory — used by OCR to protect Black students and other students of color from overrepresentation in school discipline and other harmful policies, such as dress codes policing Black hairstyles — "undermines our national values, but also runs contrary to equal protection under the law and, therefore, violates our Constitution."

"This is all a concerted effort to eliminate the protections and programs that make schools safer and more welcoming for Black students," said Feldkamp. "We're talking about removing basic civil rights protections and programs that were put in place to ensure that Black students can access our educational environment without racially disparate discipline, without teaching strategies that exclude them, without racial harassment affecting their day-to-day learning environment."

The undoing of similar policies also impacts other students of color.

Two months ago, the administration reversed an agreement reached in May 2024 by OCR under the Biden administration following a compliance review into the disproportionate impact that a South Dakota school district’s discipline policies had on Native American students.

The Rapid City Area School District compliance review found Native American students were disciplined at disproportionately higher rates than their White counterparts dating back to at least 2015-16.

As part of the investigation's outcome, the district agreed to examine "the root causes of racial disparities in the District’s discipline and advanced learning programs and implement corresponding corrective action plans." It also had to provide training to staff on its revised discipline and truancy policies and procedures, including law enforcement involvement in school discipline.

That agreement was terminated by the current administration in March.

Gutting of offices adds to challenges

A key trove of data, the Civil Rights Data Collection, allows public transparency on such discriminatory policies and informs educators of where they stand regarding their "obligation to provide equal educational opportunity."

That civil rights data collection was criticized under the first Trump administration, when former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos proposed eliminating part of the congressionally mandated collection.

While the Trump administration has not placed CRDC on the chopping block in its efforts to downsize the government, it has gutted the OCR — the office that administers the survey — and the National Center for Education Statistics, the department that helps analyze and understand the data collection.

The sweeping cuts to both have been challenged in multiple recent lawsuits, which claim that the gutting of those offices hinders the department's ability to deliver on its statutory responsibilities.

The department, however, has maintained that it will continue to fulfill its legal obligations.

"To better serve American students and families, changes are being made as to how OCR will conduct its operations," department spokesperson Madi Biedermann told K-12 Dive in a March 12 statement following the reduction in force that shuttered half of OCR’s offices and left NCES with only a handful of employees. "We are confident that the dedicated staff of OCR will deliver on its statutory responsibilities.”