When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously on May 17, 1954, in favor of the plaintiffs in Brown v. Board of Education, the "separate but equal" precedent — which had allowed state-mandated school assignments based on race for the six decades prior — ceased being the law of the land.

It had become clear that "separate but equal" was not in fact equal, as schools designated for Black children lacked updated textbooks and basic facilities like cafeterias — amenities and materials that were commonly available in White schools. The justices' decision solidified that state-sanctioned racial segregation of public schools violated the 14th Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional.

Student enrollment in K-12 public schools has become increasingly racially diverse

A handful of lower court decisions in various parts of the country — from Kansas to Virginia to Delaware — showed this was a widespread problem, leading to the case being elevated to the Supreme Court.

But a whole year passed after that decision before the Supreme Court determined a timeline for school desegregation, only to state that it should occur "with all deliberate speed."

Those resistant to the change would take advantage of that ambiguity.

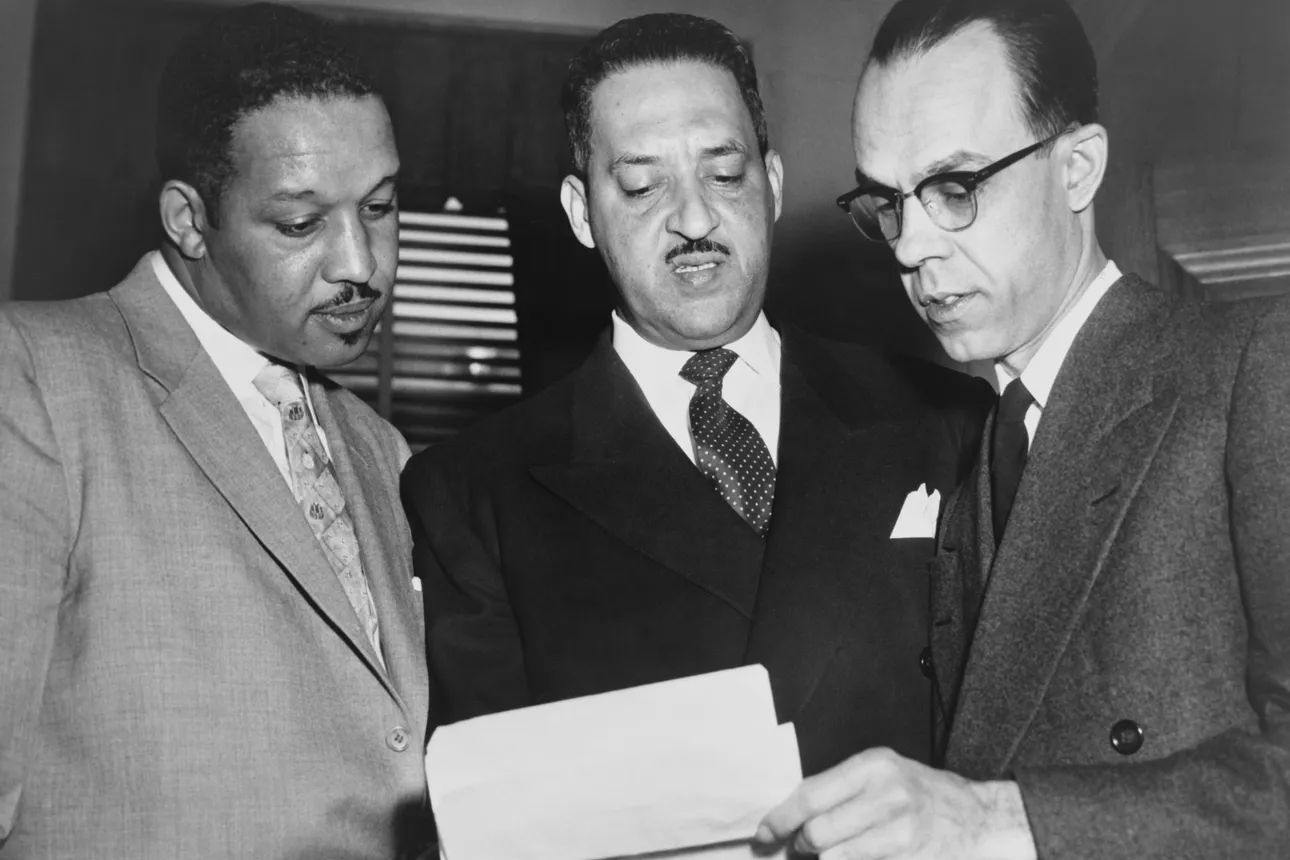

In the decade that followed, some communities quietly and peacefully began transitioning toward integration. In many communities, the NAACP, which had been instrumental in legal challenges to school segregation ahead of Brown v. Board of Education, helped facilitate local governments' compliance with the Supreme Court's ruling.

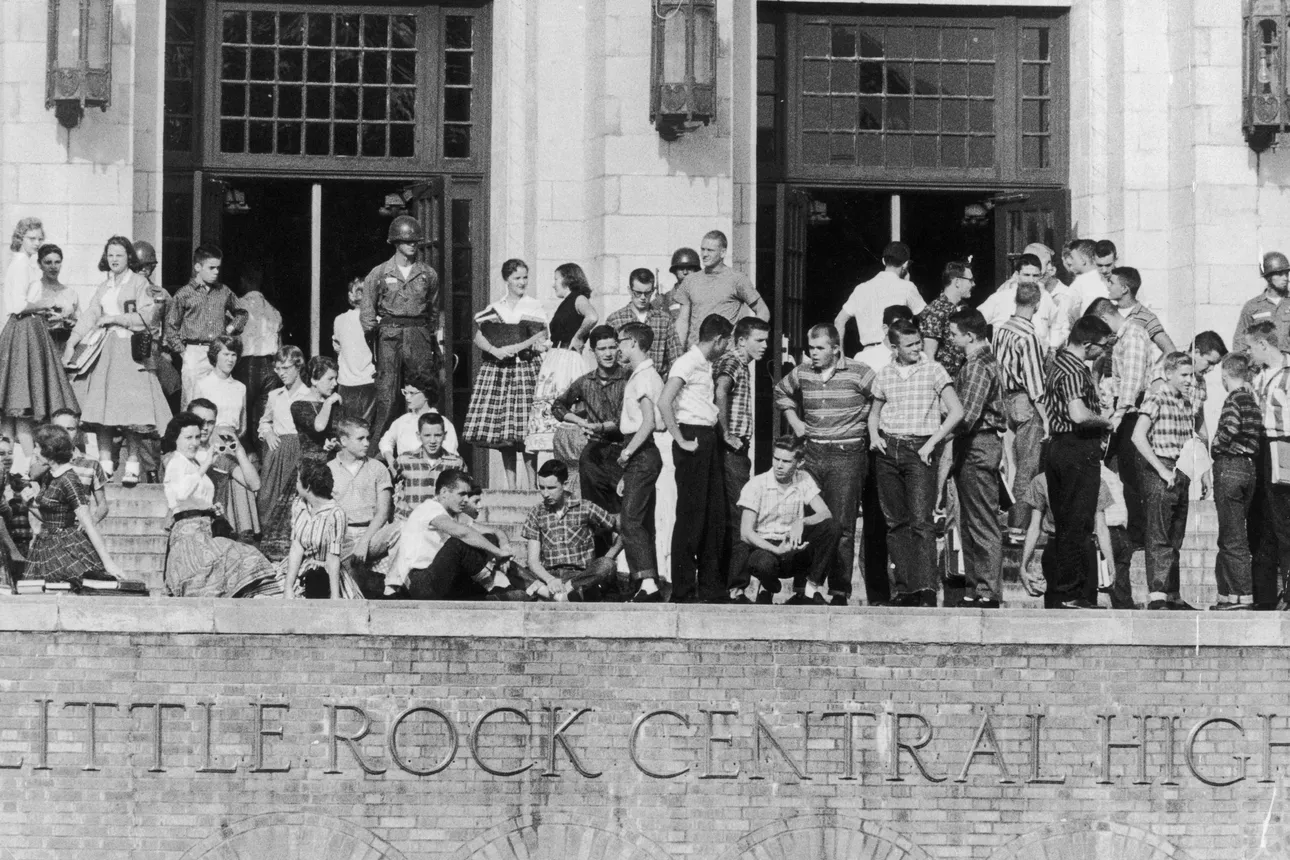

But in other localities, massive resistance from pro-segregationists erupted into violent confrontations on school campuses. In one notable conflict, nine Black students, who were enrolling in Arkansas’ all-White Little Rock Central High School for the first time on Sept. 2, 1957, were blocked from entering the school. In their way stood state National Guard troops summoned by Gov. Orval Faubus.

For weeks angry mobs prevented the nine students from regularly attending schools — until President Dwight Eisenhower superseded state leaders by federalizing the National Guard and sending U.S. Army troops to escort the students into school, according to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Soon after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, voters in Georgia, South Carolina and Mississippi approved constitutional amendments authorizing their legislatures to abolish public education systems if they were forced to integrate by the federal government, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, an advocacy organization that challenges racial and economic injustices.

While some Black and White activists were fighting for school integration, a few Black communities were hesitant about the change. One such instance came in St. Louis, where funding for Black schools had been nearly on par with White schools.

Across the nation, when desegregation efforts began White students were not often moving into the all-Black schools — initially, it was the Black students who had to leave familiar buildings and teachers who knew them well.

Teachers from all-Black schools feared integration would eventually lead to the end of their careers if the schools they taught at wound up closing.

Their fears became reality. Between 1964 and 1972, a school district transitioning from fully segregated to fully integrated — occurring at this point mostly in the South — brought a 31.8% reduction in black teacher employment, according to a 2019 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Little Rock resident Virginia Walden Ford was a 10th grader in 1966 when she transferred from her all-Black school to Little Rock Central High. She recalled last year to K-12 Dive how she wanted to stay at her former school because she was worried about encountering racism at Little Rock Central High. Sure enough, a White geometry teacher refused to call on her and other Black students in class. It caused her to fail the class because participation made up 50% of the grade, Walden Ford said.

“I think part of the reason I fight so hard now is because my experiences in high school were traumatic to me,” said Walden Ford, who has spent the last two decades advocating for the rights of students to attend private school using taxpayer-supported vouchers.

The sluggish pace of school integration following the Brown decision fueled, in part, the Civil Rights Movement. In 1964, more than 98% of Black children in the South still attended segregated schools, according to 2017 research from the Civil Rights Project and the Center for Education and Civil Rights.

Pro-integration activists fought against Jim Crow laws, mostly in the South, aimed at maintaining legal segregation by denying or impeding employment, education and voting rights for Black individuals.

On July 2, 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color and other characteristics in public accommodations and federally funded programs.

The law strengthened enforcement of voting rights, and it specifically referred to school desegregation by stating students should be assigned to public schools without regard to their race, color, religion or national origin. It also said “‘desegregation’ shall not mean the assignment of students to public schools in order to overcome racial imbalance.”

The Civil Rights Act also gave the U.S. attorney general authority to respond to complaints of school segregation by filing court orders against school systems that were resistant or slow to integrate. These mandatory desegregation orders gave the federal government oversight of certain aspects of school district governance.

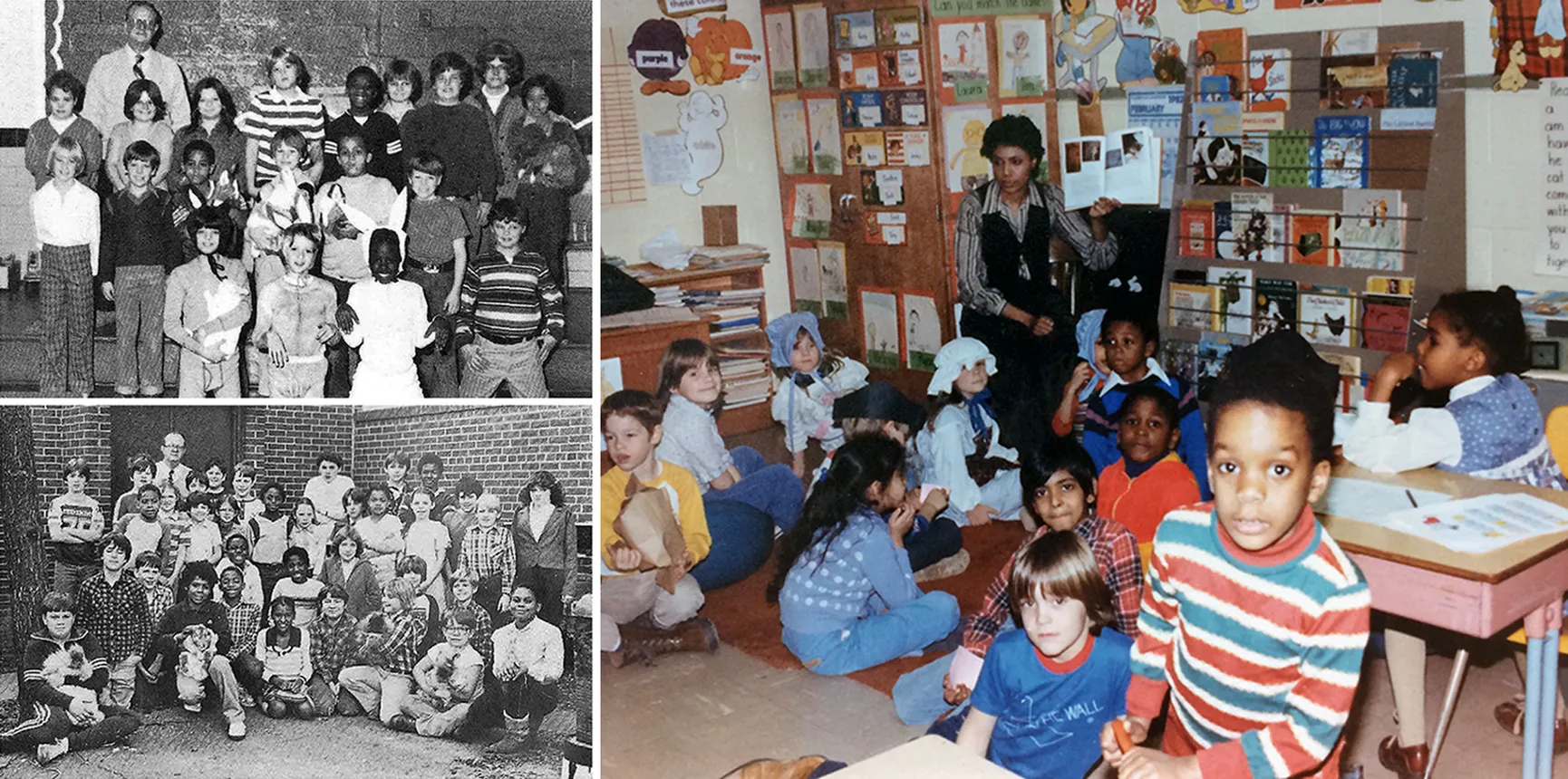

Between the 1960s and 1980s, court-ordered desegregation plans were implemented in hundreds of school districts nationwide, according to a 2022 U.S. Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies report. Although the process was meant to speed up integration, some school districts wound up spending decades under desegregation orders.

By 1969, the Supreme Court reversed its decision for schools to integrate "with all deliberate speed" and instead told school districts they were obligated to immediately terminate segregated school systems.

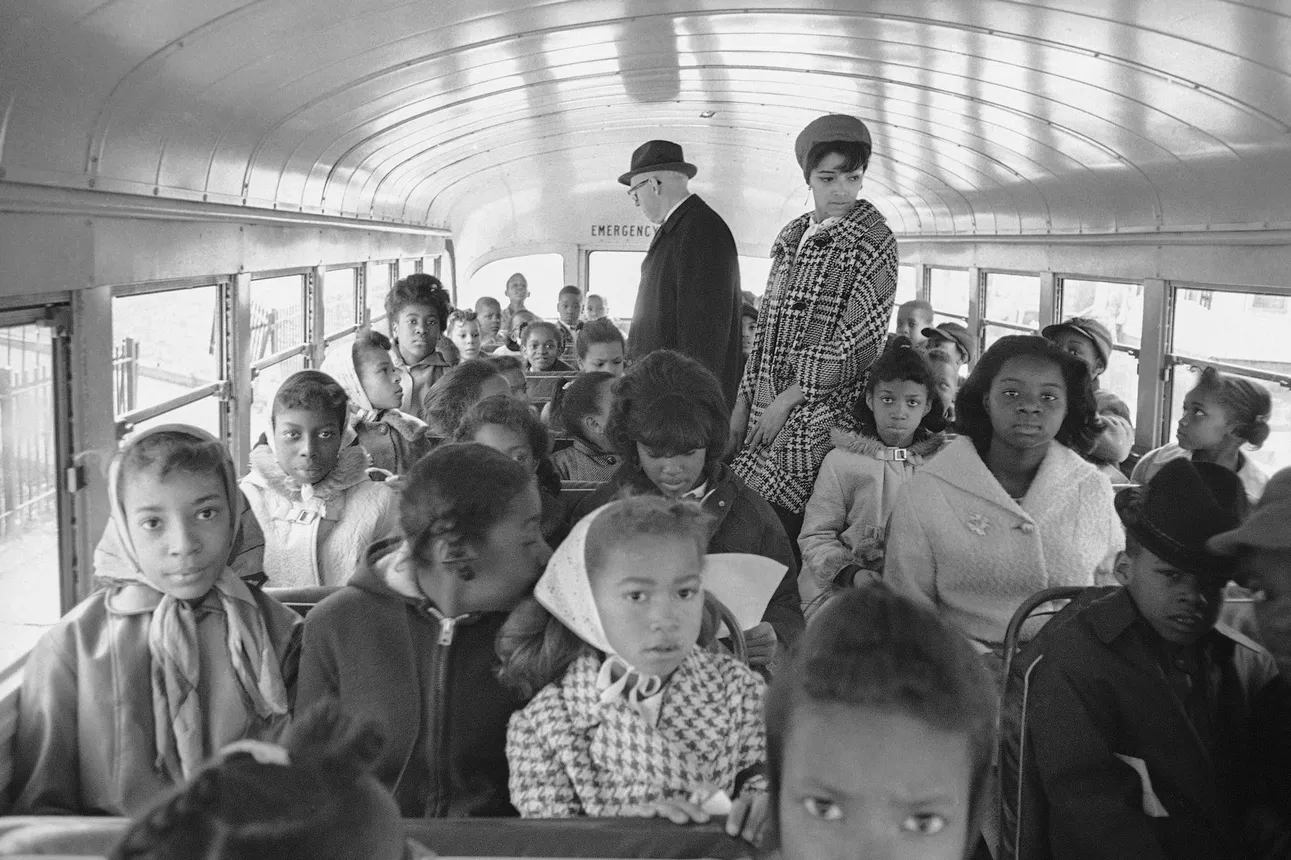

One common strategy for desegregating schools involved voluntary or mandated busing of White students to Black schools and Black students to White schools. In the Supreme Court's unanimous 1971 ruling in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, the justices approved such busing to achieve racial balances in schools. Time would show that the court decision would help to speed up integration efforts in areas refusing to change, but it was largely unpopular among both Black and White families.

Researchers over the decades have found mixed results from busing on the academic, social and emotional impacts for children. Some critics called the practice in cities like Boston and Los Angeles "disastrous" — with Black children enduring long bus rides to reach mostly White schools, while a large number of White middle-class families fled urban centers to avoid their children's assignment to predominantly Black schools.

But others felt differently. Some Black adults, reflecting on their childhood experiences being bused to predominantly White schools, have said they valued the exposure to diverse classmates and to the variety of academic and after-school programs.

For the most part, the court-ordered busing approach worked to create more racially balanced schools. School integration peaked by the late 1980s, with most Black students attending desegregated schools and 44% attending majority White schools, according to the Learning Policy Institute. Additionally, according to the U.S. Department of Education, at the height of school desegregation efforts in the 1980s, the achievement gap for 13-year-old Black students had decreased by more than half in reading and nearly half in math.

Some of the local busing agreements, meanwhile, carried into the late 1990s and even the 21st century. North Carolina's Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, for instance, ended its busing program in 2001.

As busing fell out of favor — but some districts still had to comply with court-ordered desegregation agreements — another strategy emerged: the creation of magnet schools and school choice options.

However, in developing these options, segregated school systems needed to ensure their plans would make progress toward racial balance, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in 1968 in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County.

Public and private school choice increased in the 1990s, with Education Department data showing the percentage of students enrolled in their assigned public school decreased from 80% to 74% between 1993 and 2003.

At the same time, enrollment in public school choice programs grew from 11% to 15%. Enrollment in religious private schools stayed stable at 8%, and enrollment in nonreligious private schools rose from 1.6% to 2.4%.

However, some blame the expansion of school choice for the resegregation of schools in certain localities. This is a debate that continues today.

Between 1991 and 2009, more than 200 mid- and large-sized school districts were released from desegregation court orders. Increased activity to end federal oversight of desegregation plans came after a Supreme Court decision in 1991's Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell. That 5-3 ruling found that court-ordered desegregation plans were "intended as a temporary measure to remedy past discrimination."

In a 2020 paper, The Century Foundation, which advocates for racial and economic equity in education, identified 185 districts and charter schools that consider race and/or socioeconomic status in their student assignment or admissions policies. A quarter of those schools were under some type of legal desegregation order or agreement, according to the foundation's analysis of National Center for Education Statistics data from the 2018-2019 school year.

Segregation climbed back up in most regions after 1988

Some research has found positive outcomes for school districts that had been under desegregation plans but reached "unitary status" — or when a district has eliminated school segregation as much as possible. For example, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 2007 found districts that had obtained unitary status since 2000 exhibited higher levels of integration than those that were fully desegregated years prior.

Moreover, U.S. Census Bureau research from 2022 found that Black adults who were younger than 25 when a school desegregation order was implemented in their county of birth — and therefore had more exposure to integrated schools — attained better secondary, postsecondary and job outcomes compared with Black adults who were older upon implementation of a court order.

There were no comparable changes in outcomes among White adults in counties under such an order, or among Black adults who were beyond school age when a local order was implemented, the research said.

Today, 70 years after the Brown decision, much has changed: Black and White schools no longer officially exist, violent mobs are not blocking students' entrance into schools, and governors are not calling out the National Guard to keep schools segregated. Nonetheless, the quest for racially balanced schools continues for some school systems.

In fact, national data actually shows schools generally to be more segregated now than they were in the early 1990s.

In an April paper titled "The Unfinished Battle for Integration in a Multicultural America — from Brown to Now," the Civil Rights Project says that over the last 30 years, the portion of schools "intensely segregated" — with 0-10% enrollment of White students — jumped from 7% to 20%.

The nation's largest cities have some of the highest levels of segregation. In those communities, on average, Black and Latino students attend schools with non-White peers at 84% and 83%, respectively.

The resegregation of schools can be blamed largely on two factors, the Civil Rights Project said:

- The 1991 Dowell Supreme Court decision that said court-ordered desegregation plans should only be temporary, spurring action for more local control over school enrollment practices.

- School choice policies, with charter and magnet schools now being "substantially segregated."

The Century Foundation, in a 2022 paper, found that during the 2018-19 school year, 1 in 6 public school students attended schools where over 90% of their peers had their same racial background. This translates to 19% of White students attending a nearly all-White school and 15% of Black students attending a nearly all-Black school.

Even as the U.S. student population has grown increasingly racially diverse with rising enrollment of Latino, Asian and multiracial students, attaining racially diverse schools has remained out of grasp in many areas.

And seven decades after Brown, questions about using students' race as a factor in K-12 school enrollment continue to move through the legal system.

As the Civil Rights Project said: "Schools are the largest American public institution and race is the most severe social problem, so continuing conflict is unsurprising."