WASHINGTON — In Illinois' Lake Forest School Districts 67 and 115, educators are incorporating real-life skills — such as adaptability, critical thinking, communication and other 21st century competencies — into their curricula in efforts to help students succeed in K-12 and beyond.

The work is emphasized through activities like a blog for families and educators on resilience and growth mindset and a Portrait of a Learner construct that describes the competencies students need to demonstrate in addition to academic excellence.

These real-life skills are "not nice to haves. They are musts," said Matthew Montgomery, who is superintendent of both districts. "They are as important as a rich foundational experience of mathematics or the classics in literature. We cannot treat them as soft skills anymore."

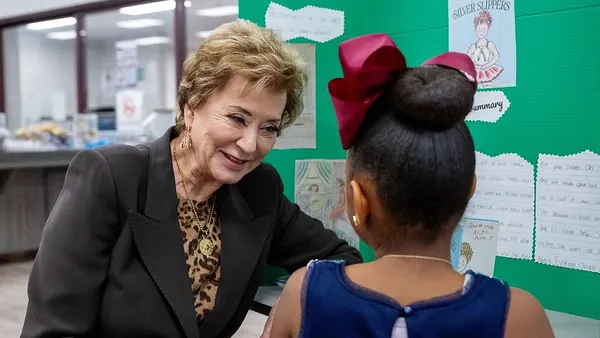

Montgomery, along with about 150 other district leaders, educators, researchers and neuroscientists gathered last week at a Real Skills for Real Life Summit to discuss what host AASA, The School Superintendent Association called the "new basics for learning."

Speakers told the summit attendees that incorporating development of these skills into the school day must be intentional, collaborative and driven by student input. The work is rooted in building a sense of belonging and compassion, as well as encouraging students to take safe risks, they said.

"Kids want to be listened to and they want to be heard. They want to be respected, connected, and they want to feel cared for. They want to have fun," said Ryan Rydzewski, communications officer at The Grable Foundation, a nonprofit focused on children's successful development.

Speakers and attendees offered practical ways schools can hone real-life skills in students, including:

- Add joy and laughter into learning moments.

- Model and normalize making mistakes.

- Offer students choice in how they engage in learning and how they demonstrate their knowledge.

- Help teachers understand their own executive functioning skills and growth mindsets.

- Guide students through holding themselves accountable for their choices.

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, a professor of education, psychology and neuroscience at the University of Southern California, said real-life skills like self awareness, curiosity, executive functioning, agency and relationship-building are critical to a student's learning process.

"We in education systems traditionally think of academic knowledge and scholarly knowledge as being separate from the experience of being a person — and psychologically and, it turns out, neurologically, that is not correct," Immordino-Yang said.

Rydzewski acknowledged that the work to build real-life skills can be hard and complex. Montgomery agreed, saying the Portrait of a Learner used in the Lake Forest districts is consistently being reexamined and improved upon based on student needs. The districts' partnerships with students, families, educators, board members and others are imperative to this work, he said.

"We do not have it figured out," Montgomery said. "I actually hope I never have it figured out, because that means there's no work to do, but we are getting closer to defining what we are trying to work on and what matters to us.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards