Senators stressed the need for federal solutions to address a mental health crisis tied to social media and technology use among children and teens during a Thursday hearing held by the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.

Proposed solutions from senators and hearing witnesses spanned from completely ditching 1:1 devices and ed tech in schools to banning young children and teens from going on social media altogether.

The conversations in the Senate are developing with a sense of urgency as research continues to demonstrate the harmful social and emotional effects of social media use on youth and as more school districts and states seek to ban or limit cellphone use during the school day.

Additionally, the rapid spread of artificial intelligence tools could exacerbate these ongoing fears about technology's impact on the youth mental health crisis, hearing witnesses said.

In the days leading up to the hearing, a coalition of education, library, and nonprofit leadership organizations sent a letter to Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee Chair Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and ranking member Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash. The coalition stressed the importance of federal support for ed tech and connectivity in schools.

Some members of the coalition include AASA, The School Superintendents Association, The Consortium for School Networking and national teacher’s unions including the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association.

“It is essential to distinguish between largely unsupervised, entertainment-driven technology use at home and the intentional, monitored, and carefully curated use of technology in schools — where digital tools are employed to support learning and prepare students for future academic and workforce demands,” the coalition’s Jan. 13 letter said.

Senators also brought up various pending bills in Congress that would address their concerns with children and teens’ excessive use of social media and technology. At the same time, nearly 20 bills looking to take on similar concerns about youth safety online are gaining traction after the House Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing and Trade advanced the package of legislation to the full Energy and Commerce Committee in December.

Cruz mentioned the Kids Off Social Media Act, a bipartisan bill he introduced last year that would prevent users under the age of 13 from accessing social media and prevent tech companies from using algorithms that feed addictive content to users under 17. Meanwhile, Cantwell highlighted other bipartisan Senate legislation such as an amendment to the Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act and the Kids Online Safety Act that she said would update privacy protections for children online and limit “exploitative designs” by tech companies.

Ed tech and the youth mental health crisis

In Cruz’s opening remarks, he praised the Federal Communications Commission’s decision in September to roll back the Biden administration’s expansion of the E-rate program to offer schools and libraries federal discounts to purchase Wi-Fi on school buses and internet hotspots.

That expansion of E-rate, Cruz said, gave students “unsupervised internet access” while also undermining parental rights. The goal of the E-rate expansion under the Biden administration, however, was to increase internet access to students from low-income families so they can complete their homework and not fall behind in their classes.

Under the Children’s Internet Protection Act, which was passed in 2000, schools and libraries receiving E-rate funds must block harmful content on their devices both on and off campus. Those requirements include denying access to content that is obscene, pornographic or otherwise harmful to students.

CIPA also “requires districts to adopt internet safety policies, monitor online activity, and educate students about appropriate online behavior,” the Jan. 13 coalition letter said. “These longstanding requirements demonstrate both the seriousness with which schools approach online safety and the robust legal architecture to protect students that is already in place.”

Cantwell pushed back on comments against the E-rate program.

“Congress is obligated to act,” Cantwell said, but rather than “focusing on threatening E-rate connectivity for schools, I think we should be passing meaningful protections for kids’ online privacy, regardless of whether they’re accessing the internet from home or school.”

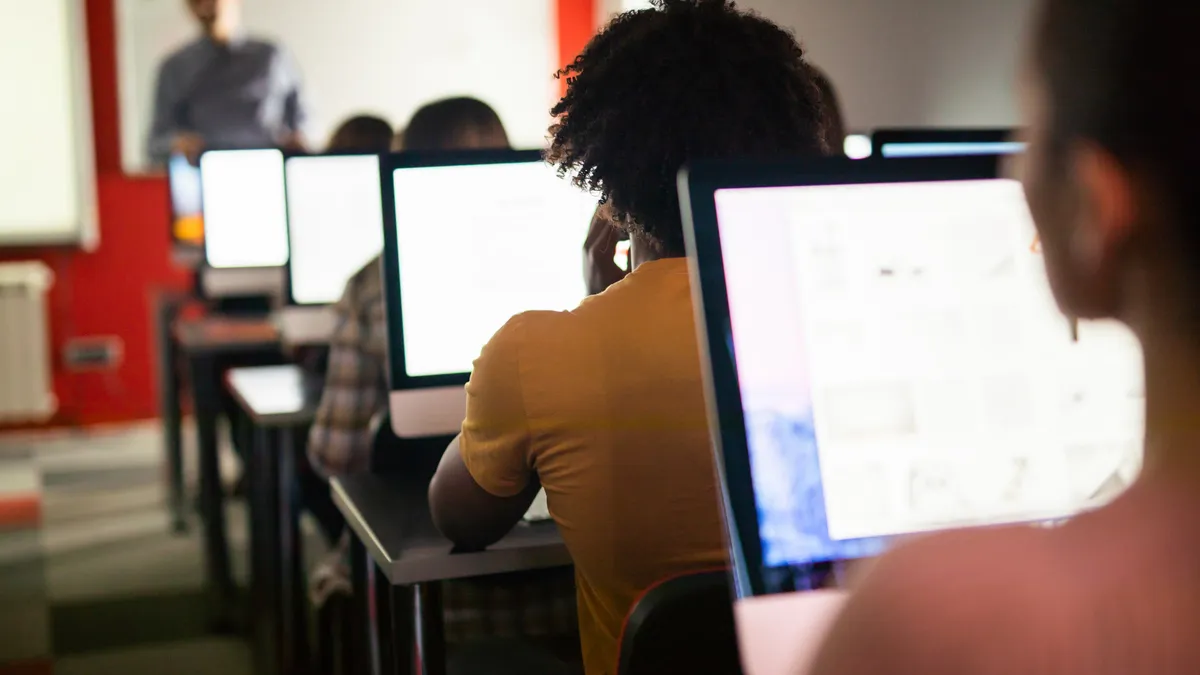

Cruz also questioned during the hearing “whether assigning personal devices to children is actually improving academic outcomes or doing more harm than good.”

Two witnesses supported eliminating 1:1 devices in schools, which became widespread during the COVID-19 pandemic when districts had to operate classes remotely for many months. The witnesses, Emily Cherkin, founder of The Screentime Consultant, and Jared Cooney Horvath, director of education professional development company LME Global, called for a return to traditional analog learning for younger students followed by the integration of technology into academic instruction during later years once key skills are understood.

Despite a surge in ed tech over the past several years, Horvath said students’ proficiency in digital literacy has dropped between 2018 and 2023 as seen on the global assessment known as the International Computer and Information Literacy Study. “So clearly, the secret to learning how to use tech is to not use tech,” Horvath said.

Education organizations in the Jan. 13 letter denounced the idea of banning all technology in classrooms, however, saying that the government instead would better serve the public by adequately funding schools with professional development and technical support to ensure schools have the most effective safeguards and online filters on their devices.