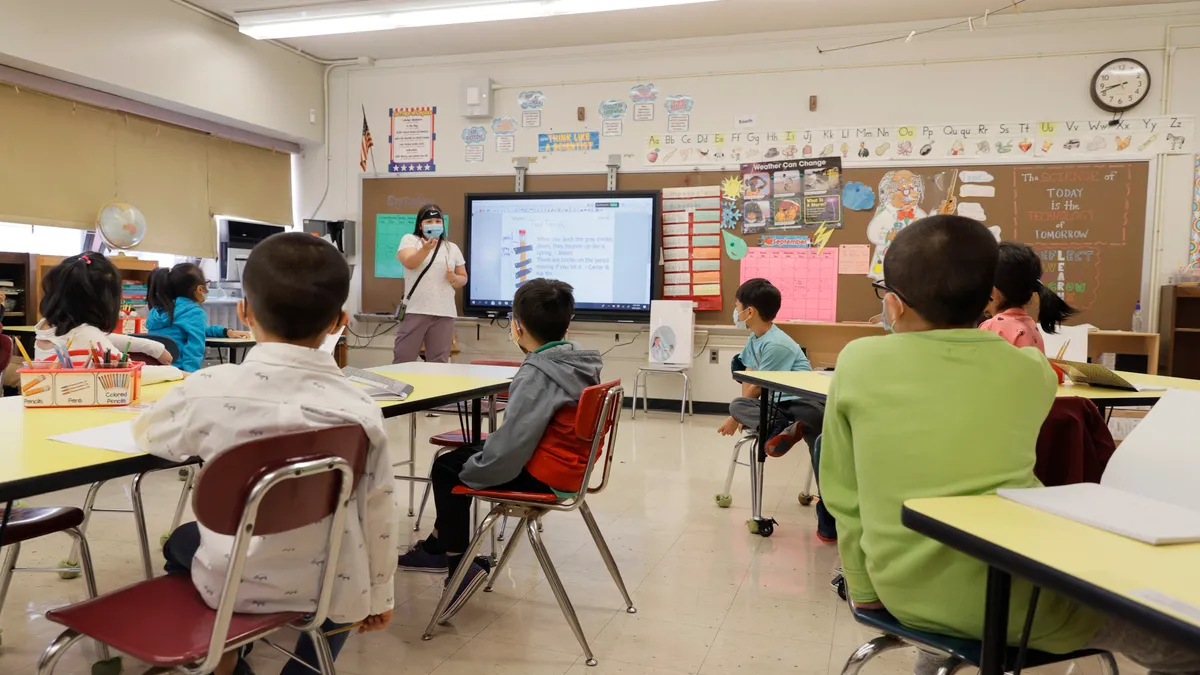

The education sector was still feeling effects from the Great Recession when the coronavirus pandemic shuttered school buildings this spring, sending the country into economic shock — one that is expected to be much worse than the 2007-2009 recession.

Prior to the pandemic, more than 20 states were spending less per K-12 pupil post-Great Recession, and in nine states, those expenditure levels were still declining. Across the nation, cuts to state education budgets made during the last recession are being linked to sizable and long-lasting losses in student achievement and outcomes.

Here, we've gathered insights from experts and reports about what financial issues district leaders should watch out for as they navigate the 2020-21 school year.

Federal education aid

If the current recession follows in the footsteps of the last one, it will likely hit K-12 schools hardest where state revenues account for a larger portion of district budgets. While reliance on state funding varies greatly across the nation, data from the Great Recession indicates Hawaii, Alaska, New Mexico, Arkansas, Vermont, Minnesota, Idaho and Washington could be among the states most vulnerable.

More recent data analyzed by the Congressional Research Service shows similar trends during this recession: All education budgets relying mostly on state and local revenues to fund K-12 are most at risk.

Many states rely heavily on state funds for K-12 budgets

And while emergency federal funding is making its way to districts to offset budget cuts, it’s not all been distributed. According to a July update from Congress, only 4% of $16.1 billion from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act that can be used for K-12 education has been spent, "only covering a portion of unanticipated costs and lost revenues associated with the pandemic."

Exactly how much federal money will filter down to public schools is unclear, but estimates from the Learning Policy Institute put that number at an additional $286 on average, per pupil, from CARES funding. Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab, an education finance research center, suggested similar numbers to Education Dive via email, with funds for elementary and secondary schools providing approximately $270 per pupil and an additional $40 per pupil from CARES’ Governor's Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Fund.

Estimates from legislators and analysts suggest future federal stimulus funding, which is still a moving target, would be about $1,200 per pupil.

But the U.S. Education Department is requiring districts to choose between funding public and private schools or strictly Title I schools.

Breakdown of K-12 budget shares by state

Lower district budgets

Most states were slow in warning their districts of revenue shortfalls and changes to K-12 budgets. By mid-May, fewer than half of states had warned districts of K-12 cuts. Most states have now revised their revenue projections, with state revenues projected to drop from 1% to 26% from 2020 to 2021 from pre-COVID-19 projections, according to data collected by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

But fewer have cautioned about how they might impact K-12 education budgets, said Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown’s Edunomics Lab and an education finance expert.

Still, districts should draft flat budgets, Roza said, or even with a 5% to 10% cut if they don’t know yet how they will be impacted by states’ declining revenues. She also cautioned against dipping into reserves, because the nation is preparing for a multiyear recession.

"Not making cuts now means you’ll have to make cuts later," she said. "Not restructuring now means you won’t have reserves next year and people will be paid more [due to raises], so you’ll have twice the problem."

Tax revenue decline projections by state

Based on random sampling and analysis from Edunomics Lab, districts already are cutting budgets. Many districts have begun with a trim-from-the-top approach — where budgets are cut from the perimeter rather than eliminating full-scale programs that have significant implications for stakeholder groups and could create pushback. Trimming from the top includes cuts to the central office, afterschool programs, contractors and other areas that can be eliminated without approval from the school board.

Field trip and some school building maintenance allocations will likely be repurposed as well, considering the pandemic's impact on health and safety makes it unlikely for schools to proceed with either, Roza said.

Based on the research center's tracker, more districts are choosing to furlough employees temporarily not working, such as bus drivers, as compared to the Great Recession. Districts looking for major cuts, however, will likely lay off staff and teachers.

Layoff decisions

Multiple researchers and district leaders have warned against seniority-based layoffs, which have been shown to disproportionately impact students with the greatest needs in hard-to-staff schools.

A California law that requires the newest teachers to be laid off before their senior colleagues, for example, was challenged during the 2008-2009 financial crisis for disproportionately impacting black and brown students. Nick Melvoin, a teacher at the time, recalls that the decision to preserve veteran teachers left a majority of his newer colleagues with pink slips and a "rotating parade of substitutes" in his school.

"If a district has negotiated seniority-based layoffs with their union, I would recommend they reopen their contract [negotiations] and take a look at that now," Roza said.

Some districts are considering alternatives to pink slips. Melvoin, now a member of the Los Angeles Unified School Board, said he is looking at ways to repurpose staff. Bus drivers, for example, could become tutors or phone-banker workers designated to call students who aren't logging on during the school day.

Melvoin warned against the "inevitability to teacher layoffs," saying districts should make layoffs a last resort rather than a go-to option. But if districts choose that route, Melvoin said, they will have to weigh tradeoffs in order to determine how to least impact students. If a district is trying to save $10 million, he said, it could lay off 100 veteran teachers (who cost more than newer teachers) or a greater number of new teachers to amount to the same cost.

Extra spending

Some areas of spending, like cleaning and sanitation allocations, will increase this year, districts report. Nurses and custodial staff for health and safety monitoring and cleaning will also likely be preserved.

Estimates from AASA, The School Superintendents Association, released in May show it would cost an average district approximately $194,045 for personal protective equipment, $1.23 million to hire additional staff such as custodians and nurses, and $116,950 for health and disinfecting equipment.

Roza said she has also noticed districts moving forward with teacher raises, which she cautions against, considering attrition rates will be lower during a recession. Raising pay is in line with trends from the Great Recession, when districts made similar decisions to follow through on promised pay raises instead of revisiting their multiyear contracts.

That decision left districts making deeper cuts, hurting them in the long run.

"When the rest of the world was hiring again and making raises, districts were still not, because they had given raises during the recession," Roza said. This time, she said, districts should "figure out how to be a little more nimble instead of committing to raises when they are out of step with the labor market."

Research released in August from Education Next also advises against cuts to instruction, in light of data from the Great Recession suggesting state budget cuts can have a long-lasting impact on student outcomes and achievement

State budget shortfalls compared to previous recessions

Enrollment trends

Low enrollment and attendance numbers also have the potential to hurt funding. In Texas, for example, funding is based on daily average attendance and could be withheld if the district is not open for in-person instruction.

"If a school had an outbreak and they needed to close down, and they won’t get funding for that, that has huge consequences for a school district," said Kevin Brown, executive director of the Texas Association of School Administrators. "Essentially, you’re obligated to pay your employees, which makes up about 90% of your budget … and if you don’t have funding to do that, then what does a district do?"

Melvoin also thinks that as families take flight from cities to more affordable areas, enrollment in urban public schools could decline. But the lost students could be offset by those who can no longer afford private school tuition and transition to public school.

While many are looking to the Great Recession as a signifier of what's to come, Melvoin said the coronavirus-induced economic decline is not the same. "But this is beyond that in some ways, on a different level," he said.