Do public schools violate parents’ religious freedom when exposing students to books on gender and sexuality without notifying parents or allowing them to opt their children out? The Supreme Court’s answer was — as is often the case: It depends.

The high court's 6-3 decision in Mahmoud v. Taylor was released on the final day of its term last month, and the 41-page majority opinion — which was a win for religious parents wanting to opt their children out of LGBTQ+ material — left education policy experts with more questions.

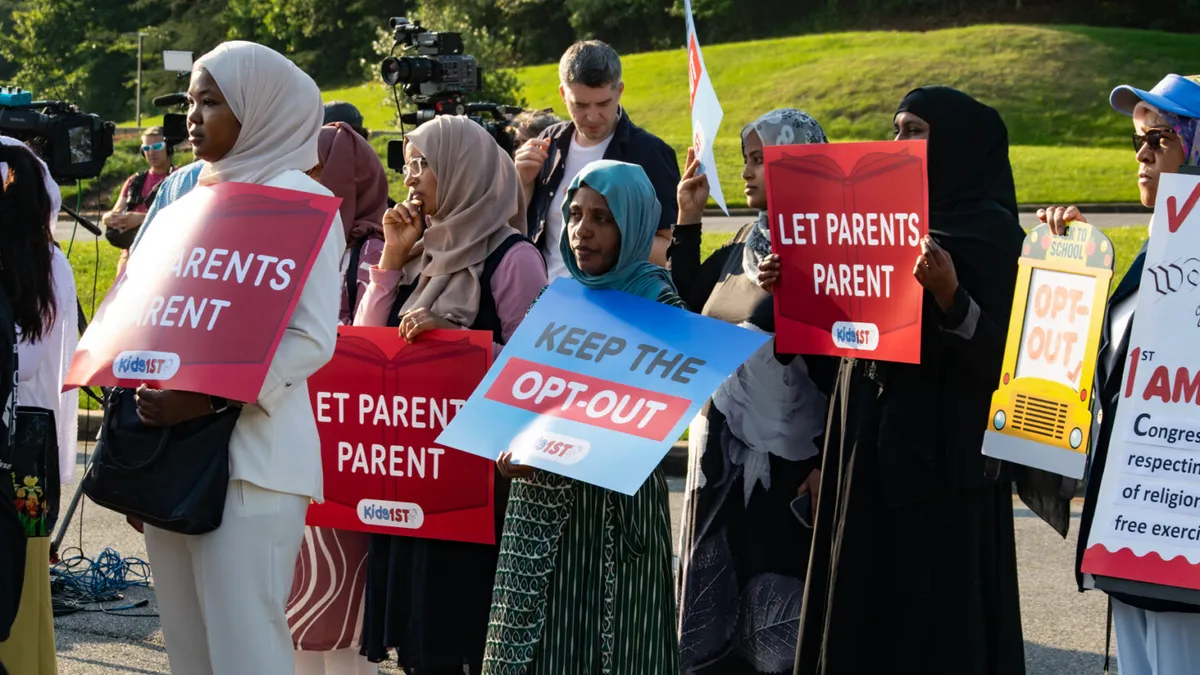

The high-profile case arose after Maryland's Montgomery County Public Schools walked back its decision to grant opt-outs to parents for a new LGBTQ+-inclusive curriculum rolled out in elementary schools. The district’s school board rescinded the opt-out policy less than a year after the curriculum went into effect in 2022-23, due to what it called "unworkable burdens" that came with an influx of parents' requests.

After the 4th circuit and a district court ruled in favor of Montgomery County schools, the high court last month overruled those decisions, saying, "the practice of educating one’s children in one’s religious beliefs, like all religious acts and practices, receives a generous measure of constitutional protection.”

Here’s what the ruling means for schools.

Most districts may not have to change much — for now

The Supreme Court’s decision granted a preliminary injunction previously denied by the lower courts, temporarily allowing MCPS parents to excuse their children from instruction related to LGBTQ+ storybooks while the lawsuit proceeds in the lower courts.

That means it doesn't apply to other school districts — for now.

"The handwriting is on the wall," said Michael Rebell, a law and educational policy professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College. "If you have a policy that's very, very similar to what was going on in Mahmoud, I think you'd be wise to change it.”

Maryland's largest school district put LGBTQ+-inclusive books among other titles on classroom shelves for elementary children to choose from when learning language arts skills. Some of those titles included: “Intersection Allies,” “Prince & Knight,” “Love, Violet,” “Born Ready: The True Story of a Boy Named Penelope,” and “Uncle Bobby’s Wedding.” These books, Justice Samuel Alito said in the majority opinion, "suggest that it is hurtful, and perhaps even hateful, to hold the view that gender is inextricably bound with biological sex.”

However, in her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said the majority opinion should not result in schools pulling books from classroom shelves. Rather, the injunction applies to using the books as part of classroom instruction.

"The line the Court drew seems bright: If schools use contested materials instructionally — especially in ways that make exposure unavoidable — parents have a right to know and a right to say no," said Robert Pondiscio, a senior fellow at American Enterprise Institute, in an analysis of the decision.

The case — or another like it — may work its way back up to the Supreme Court

As the case goes back to the lower courts for a decision, it may eventually reappear on the Supreme Court's docket and give more clarity to districts on what kinds of opt-out policies they should craft through a broader decision, said education lawyers.

"It was a fact-intensive analysis of this particular case that unfortunately gives some guidance to schools going forward but leaves a lot of questions unanswered to be hashed out in the future, in lawsuits or in other ways," said Sarah Konsky, professor and director of the Jenner & Block Supreme Court and Appellate Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School. Konsky's clinic represents parties in Supreme Court and appellate cases. "This will be a continuing discussion and likely source of litigation in the coming years."

If this specific case doesn't work its way back to the Supreme Court, it's likely that another will, said Konsky.

Overall, the issue of parental rights is part of a much broader reckoning in the nation over First Amendment rights and will likely resurface in some capacity that districts should look out for, education lawyers agreed.

What should districts' policies look like?

While the decision should give districts pause on their own policies, exactly how they should — or shouldn't be — reconfigured isn't exactly set in stone. The age groups and subjects that warrant opt-outs was not spelled out in the Supreme Court’s decision.

In the meantime, "the case leaves us with a bottom line that if a school policy is substantially interfering with the religious development of a child in a public school, that that is likely going to pose First Amendment problems," said Konsky.

Districts, she said, may take into account multiple factors when setting these policies, including what counts as "substantial interference," the nature of the educational requirement or curriculum, and the age of the child. The majority opinion says that educational requirements targeted toward very young children may be analyzed differently from educational requirements for high school students, for example.

Topics like sexuality are likely to trigger more religious objections, and presenting them in one particular course or period of the day may make opt-outs and advance notice more logistically practical for schools, said Sonja Trainor, executive director of the National School Attorneys Association.

Schools should also think about how they will ask parents to articulate their request, how accommodations are discussed, and how to provide notice to parents with approved opt-out requests.

Pondiscio's analysis shows that although opt-outs are likely unnecessary in situations when a student is checking out a library book independently from the school library, Mahmoud leaves open the question of whether placing an LGBTQ+-inclusive book on the classroom shelf for students to choose from during a lesson requires opt-outs.

"The classroom library didn’t build itself," he said. "Teachers or other school district personnel chose what went on those shelves. And students made their selections during instructional time, under adult supervision, as part of a structured literacy program. In other words, 'We didn’t assign it' may not be much of a defense."

Districts avoiding MCPS' situation should prepare to engage with parents

Schools should be engaging with parents to accommodate them and collaborate as they set curriculum and opt-out policies, said Konsky — especially because the Supreme Court seemed concerned in MCPS' case that there was not an effort to work with parents.

"It would be wise to be thinking about that at the outset, before a lawsuit," and begin engaging with board members and other stakeholders about how to accommodate religious differences in the curriculum, said Konsky. "If schools are aware of this decision and are thinking ahead of time about how and to what extent they're able to accommodate student opt out requests, they'll be ahead of the curve as these issues are playing out."

Overall, school attorneys are warning that the case will likely lead to more parental requests that schools provide notice, opt-outs or both.

"The gap between how courts think 'curriculum' works and how it’s actually implemented in elementary classrooms is vast," said Pondiscio. "And that means schools will likely keep finding themselves on the receiving end of angry phone calls — and possibly lawsuits — from parents blindsided by what their children bring home in their backpacks."

Dive Awards

Dive Awards