As a first-year teacher in Hawaii, Kareem Farah taught his high school math classes as he had been trained — at the beginning of each class, he'd give a lecture on the material, then give students an assignment based on the lecture, and then move on to the next part of the curriculum.

The problem was that he could tell the students weren't engaged during his lectures, didn't understand the material and didn't perform well on the activities. The instructional format also frustrated Farah.

"And then you just go on to the next day and pretend like nothing happened, and that is — and was — teaching as I knew it," he said.

Now, 10 years later, Farah is hoping to disrupt the traditional model of instruction through a nonprofit he founded with a fellow teacher, Robert Barnett.

The Modern Classrooms Project approach to classroom instruction centers the students as leaders of their learning rather than the teachers. The strategy eliminates whole-class lectures and instead uses instructional videos created by the students' classroom teachers.

Students watch the videos at their own pace during class, and the teachers' time in class is spent helping individual students master concepts and demonstrate their knowledge before everyone moves on to the next unit of lessons. Teachers also monitor students' progress daily to keep them on track.

"When you create an effective student-centered learning environment, like the one that we've created, students have greater control over their learning," Farah said. "When we transitioned out of this [traditional] model, the first thing you would see is an instantaneous decline in my stress level and my students' stress level."

'A new way to teach'

After teaching in Hawaii for three years, Farah moved to Washington, D.C., for the 2016-17 school year to teach at one of the city's high schools, where he met Barnett.

Farah had kept the same traditional class lecture structure, continuing to feel stifled. "A lecture format is comically ineffective," Farah said. "It's ineffective if everyone's at the exact same spot in the learning experience. It is fundamentally broken when you have a diversity of learning levels and social-emotional levels."

As Farah tells it, Barnett noticed Farah's exasperation and showed him how he led his classes using self-created instructional videos. Both educators experimented and developed what is now the Modern Classrooms Project approach, which Farah said can be used for all grade levels and academic courses.

"This is what the problem is with K-12 ed: We keep throwing strategies at a broken instructional model. You can't throw strategies at a broken approach. You need to change the approach."

Kareem Farah

Co-Founder and CEO of Modern Classrooms Project

To ensure students are mastering concepts and not simply jumping from one lesson to the next, students take "mastery checks," or short assessments to measure their progress. Students cannot advance to the next lesson until they master the previous skill. The number of lessons in one unit of study is determined by the teacher.

This instructional format requires teachers to plan entire units of study in advance, including the videos. This can take quite some time for teachers trying this approach for the first time. The advantage, however, is that the videos allow students to self-pace their learning by replaying lessons they don't understand or by fast-forwarding through lessons of skills they've already mastered, Farah said.

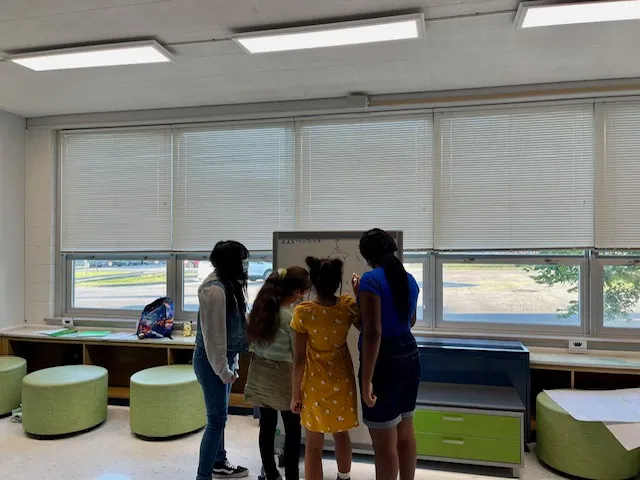

Students also spend in-class time working one-on-one or in groups with the teacher or with peers. Farah has referred to the format as a "controlled chaos environment" as students work independently or in groups during class time.

Since students watch the videos and take the mastery checks in class, Farah said, the approach differs from the flipped classroom concept that requires students to do research or watch videos at home before the class lesson.

"I know it's hard for people to wrap their head around, but we're just a new way to teach," Farah said. "This is what the problem is with K-12 ed: We keep throwing strategies at a broken instructional model. You can't throw strategies at a broken approach. You need to change the approach."

Benefits of blended learning

As Farah and Barnett tweaked their model, they shared it with other educators at their school. Word spread, and soon there was growing interest. Modern Classrooms Project launched in 2018 by helping a small group of teachers learn the model.

The co-founders left teaching to work full-time on the Modern Classrooms Project. They anticipated that by 2022, the organization would train about 300 teachers in a free course on how to use the model. By mid-Feburary of this year, about 50,000 teachers had taken the course, Farah said. Additionally, 7,000 teachers have participated in a fee-based virtual mentoring program.

In 2022, the organization had earnings of $7.7 million with 30% coming from school systems and 70% collected from donations, Farah said. There are 24 full-time staff members at Modern Classrooms Project.

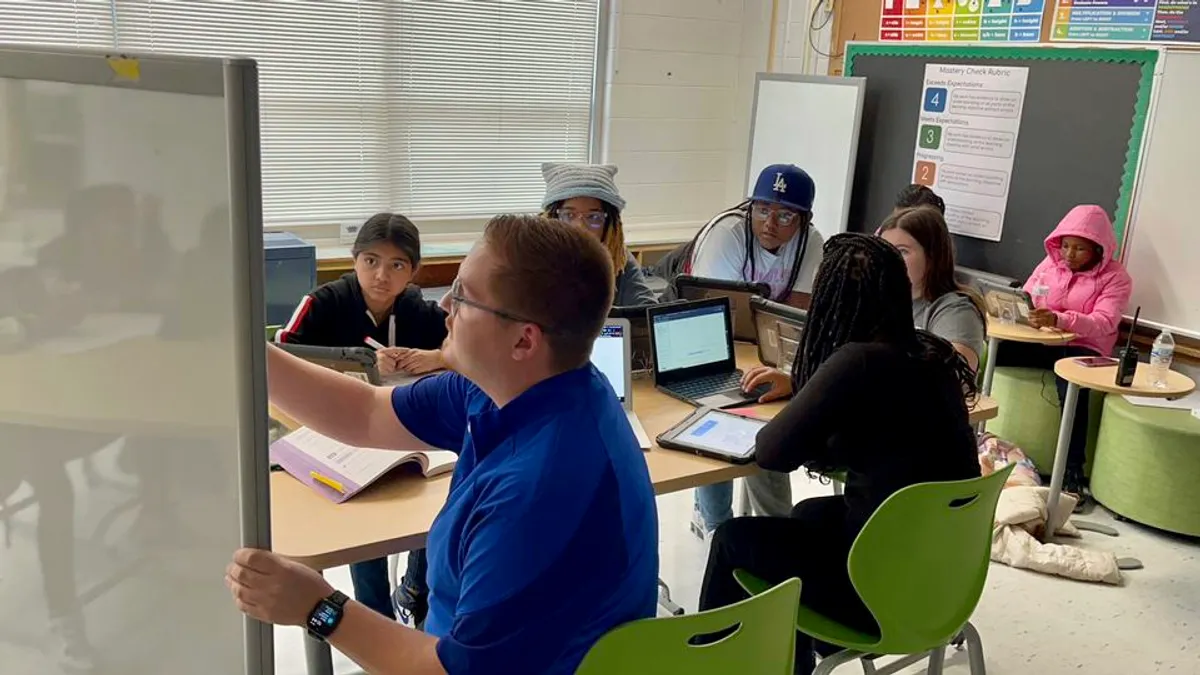

Early-career teacher Cory Rawlins uses the Modern Classrooms Project approach for his 6th grade math classes at the Grace M. James Academy of Excellence, an all-girls middle school in Louisville, Kentucky. In summer 2021, as the school was planning for its second year of operation, administrators encouraged teachers to try the instructional approach.

It was Rawlins' second year teaching — he had spent the previous year at the school teaching mostly online because of pandemic restrictions. With the support of administrators, he and other teachers designed their lessons for the upcoming school year using the Modern Classrooms Project approach. It was vastly different from what he was taught in teacher preparation courses on how to organize instruction, which was that the teacher was to stand and give lessons to students seated in rows.

In unveiling the new approach to students and parents, Rawlins said he reserved the first few weeks of school to explain how the instructional videos could be accessed, how to submit revised assignments, how to ask him for help and other logistics.

As he and the students began using the approach, he said he quickly noticed the benefits, including students' ability to replay parts of the instructional video if they didn't understand a concept or if they were absent from school. Additionally, he noticed that the self-paced structure was helpful for both the students who needed more time reviewing concepts and those who were ready to move on to more challenging work.

But he also noticed his 25-minute long videos did not hold the attention of his students. He edited the lessons so each video ran about 5 to 10 minutes long.

Rawlins advises teachers who are interested in the model to try the approach with three lessons over a three-day period. He also recommends clearly communicating to students the expectations and deadlines for completing lessons and assignments. In his classes, he schedules 10 lessons over a two-week period.

Lastly, Rawlins wants to address a myth that the approach means teachers are hands-off or not involved in the students' learning. He says that every day, he has a small group lesson with students who need more explanation about ratios, percentages or algebra concepts. On some days, he conducts a whole group lesson.

"It's the blended learning piece that's crucial," Rawlins said. "I think that it has freed me up in the classroom to move around and create relationships with students and to have a pulse of what students understand and the misconceptions that they have.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards