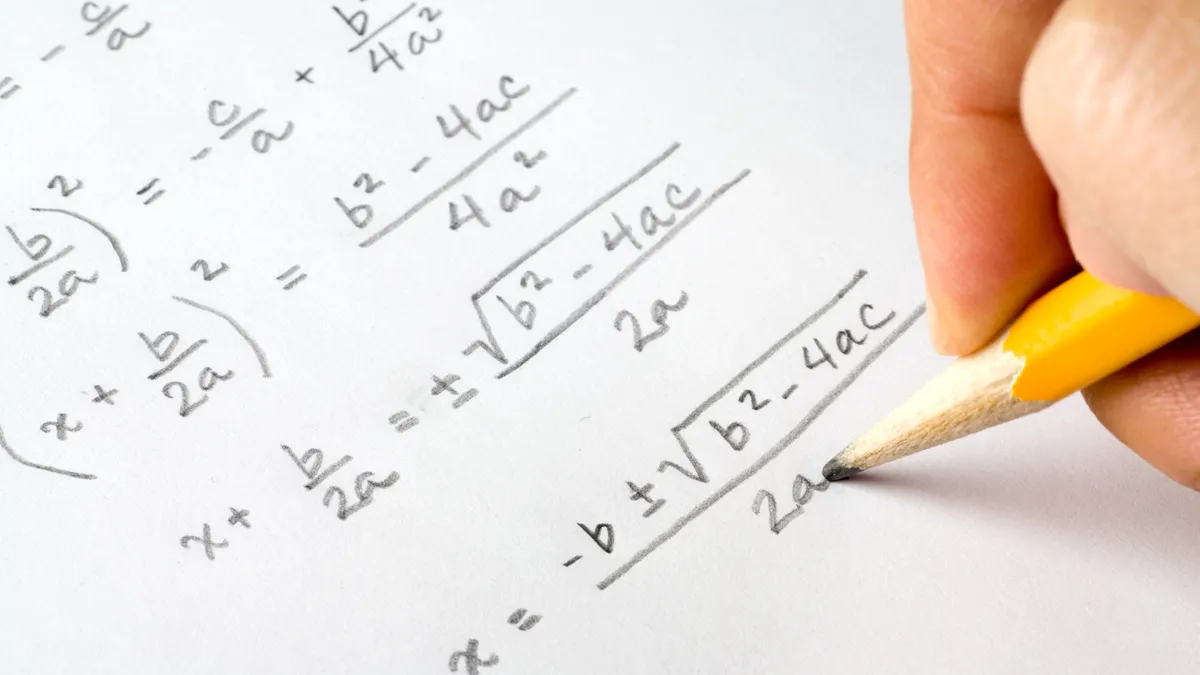

For 10 years, Kaitlin Jenkins graded her high school English students according to the traditional A-F model she grew up with and was taught in educator preparation courses. But when a student asked her why an assignment marked with an 89.2% (a B) was not a 90% (an A), she struggled to justify the grade.

“I had to really stop and have a painful conversation with myself about why that was, and I realized it was because I was not grading for equity,” said Jenkins, a 9th and 12th grade English teacher at Colfax High School in Colfax, California. “I was equating time spent [on the assignment] with [subject] mastery, which is not the case.”

Last school year, Jenkins began eliminating all extra credit opportunities and behavior-related points for tardiness and participation from metrics for end-of-course grades, focusing instead on a simpler and singular measurement system for student advancement toward mastery of academic standards set by the California Department of Education.

“It's really hard to look at your own performance in the career that you love, and that you've chosen to do for your life, and realize that the first whole decade-long chunk of it was not equitable — that what you were doing was not great for kids,” Jenkins said. “That feels icky inside.”

Grading students’ work has never been a favorite task for teachers. Some elements of grading are subjective, and the task is tedious, teachers say. It’s a struggle that’s being amplified during the pandemic as educators continue to have high expectations of their students but want to recognize the burdens and barriers the novel coronavirus may have on student performance.

School districts that were lenient in the spring with grading policies, however, are not giving much flexibility this school year, which is worrying some education experts about the equitable evaluation of students’ performance during the pandemic.

As the first grading period closed this fall in a challenging school year, some districts discovered a concerning rise in Ds and Fs despite efforts to create small in-person learning groups, extra tutoring times for struggling learners and other supports. For example, Sweetwater Union High School District in Chula Vista, California, released data in late November that shows an 8 percentage point increase in Ds and Fs over the last school year.

“It's just all around equitable, because I know at the end of the day that all I've asked you to do is show me you can do these standards.”

Kaitlin Jenkins

English teacher at Colfax High School in Colfax, California

Additionally, an analysis by Fairfax County Public Schools in Fairfax, Virginia, of first quarter grades for middle and high school students found an 83% increase in Fs compared to the first grading period in the 2019-20 school year. The data shows while all student groups had increased failure rates early in this school year, students with disabilities and English learners had the highest rates of Fs compared to White and Black students.

“With the dramatic rise in Ds and Fs we are realizing that common approaches to grading are not effective now or are really applicable now,” said Joe Feldman, founder and CEO of Crescendo Education Group and the Equitable Grading Project.

‘Do no harm’ approach

Many districts and classroom teachers, while not completely overhauling their grading systems during the pandemic, are currently taking a "do no harm" approach to grading, which avoids penalizing students through low grades for circumstances out of their control, such as lack of access to internet or the need to care for sick family members. Teachers also have thinned out some of their lesson plans so they make sure to hit on essential academic standards while still pacing the class for remote and in-person learning formats.

Wanda Tharpe, the principal at Dacusville Middle School in Easley, South Carolina, said grading during the pandemic has been challenging because teachers are constantly wondering if an incomplete assignment or poor performance was the fault of a student not having access to the internet or some other factor.

While the district hasn’t changed its grading policies, Tharpe said teachers are putting a lot of time into planning appropriate assignments that can be taught and assessed both remotely and in-person. Teachers also work individually with students when poor performances are recorded.

“Not knowing how long the pandemic will last, we want to make sure our students’ educations are not lagging,” Tharpe said. “We want to continue with as rigorous a curriculum as we can during this time because we want to lessen any learning gaps.”

Feldman said that, in general, there’s a reluctance to change grading practices because the A-F and 0-100 point system is so ingrained and nearly universally used. At the high school level, grade point averages are used for class rankings, course promotions, athletic participation, college applications and scholarship opportunities.

Grading is also one of the only autonomous activities teachers have, Feldman said. While local and state school systems typically provide guidance for grading structures, such as the numerical range to use for letter grades and course promotion requirements, the grading of daily assignments, tests and end-of-course grades is solely the duty of the classroom teacher. Teachers of early elementary grades typically don’t give A-F letter grades but instead provide feedback on progress through narratives.

A few school systems are tweaking grading approaches this school year in response to the pandemic:

-

In Georgia, the state board of education has approved a change that reduces the percentage weight that the Georgia Milestones end-of-course assessments will count in a student’s final grade in the course. The statewide passing score typically places that percentage weight at 20%, but for this year only, the percentage weight will count as .01%, at minimum, of a student’s final grade in the course.

-

New York City Public Schools is allowing schools to set their own grading scales, such as a 1-4, a numerical scale to 100 or an A-F system. The district is also allowing flexibilities for families in how final grades are reflected on a student’s academic record, plus other allowances.

-

The San Diego Unified School District recently changed its grading policy in an attempt to more equitably assess student achievement. The revised system requires teachers to assign letter grades for students based on “mastery of content” and allow for “reflection, revision and reassessment” in order to reach mastery levels. Separate citizenship grades will be issued to students based on behaviors, such as being prepared for class and participating in discussions.

Inequities in grading

In California, Jenkins uses a 1-4 point system for her classes’ English tests and assignments to calculate an end-of-course grade that follows the A-F system. She allows students to revise work that received low marks, but gives deadlines for when those revisions should be turned in. Her system, which is also used by the other high school English teachers at her school, was initially hard for her 9th-grade students and their parents to understand. But now, after more than three months of school, she’s receiving mostly positive feedback.

“My hope is that this pandemic has cast this much brighter spotlight on the inequities and inaccuracies and the harmful impact of these traditional grading practices.”

Joe Feldman

Founder and CEO of Crescendo Education Group and the Equitable Grading Project

This fall, Jenkins had to review skills students missed out on learning in the spring. She also eliminated one novel from the required reading list so she’d have enough time to cover all the other essential material. Still, she said her grading system takes out a lot of the guesswork for assessing students’ knowledge, particularly during the current health crisis.

“It's just all around equitable, because I know at the end of the day that all I've asked you to do is show me you can do these standards,” Jenkins said. “I haven't asked for, you know, a dog-and-pony show. I haven't asked you to scan a piece of paper with tea and burn the edges. I have only asked you to show me that you have the skills to go on to the next level.”

Feldman said traditional grading systems can disproportionately punish students who have fewer supports and create advantages for students who have more stable and supportive home environments. Eliminating grading for activities such as homework competition and participation can help remove bias in assessing student performance, he said.

During the pandemic, teachers should also consider the use of incompletes if a student is just not able to meet the requirements of a class, Feldman said. Traditionally, incomplete interim and final grades are avoided in school systems unless there is an unusual circumstance that prevents a student’s academic participation, such as a prolonged illness. But because so many students’ educations are being interrupted currently, an incomplete could more accurately reflect an individual student's situation as opposed to a failing grade, he said.

“My hope is that this pandemic has cast this much brighter spotlight on the inequities and inaccuracies and the harmful impact of these traditional grading practices,” Feldman said.

Sheldon Eakins, director of the Leading Equity Center, also supports revamping grading approaches through equitable practices. For example, he advocates for removing grades for homework and participation. He also suggests teachers allow students multiple options for demonstrating their knowledge of an assignment, a component of universal design for learning. Teachers can also ask students to honestly assess their own performances by providing evidence of their learning, essentially allowing students to use proof to grade themselves.

Teachers could even consider going gradeless during the pandemic, Eakins said.

“I don’t know if there’s an equitable [grading] approach to online learning and honestly, traditional learning,” Eakins said. “There are so many different factors that need to take place to meet everyone’s needs.”

Dive Awards

Dive Awards