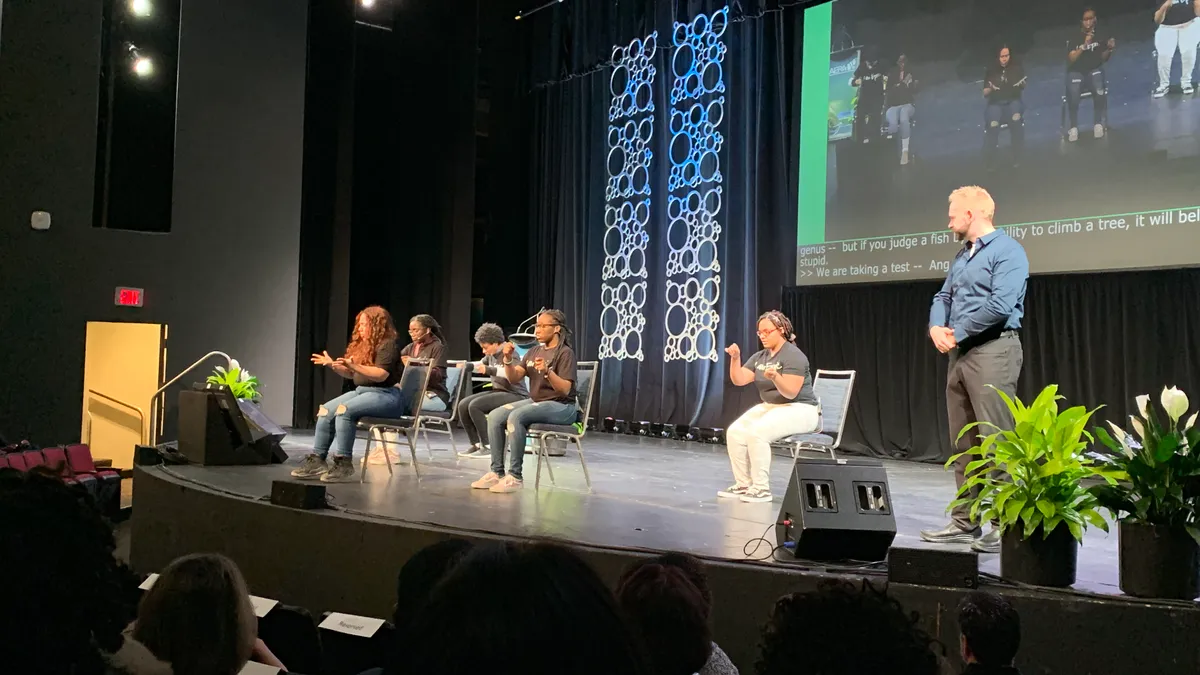

TORONTO — Dramatizing the range of emotions students feel toward standardized testing, members of the Epic Theater Ensemble, based in New York City, opened the presidential address at this year’s American Educational Research Association (AERA) conference with a strong statement against the role of testing in education.

“I already know I’m going to fail,” said one actor, with the sound effects of a ticking clock in the background. Another portrays a near panic attack from test anxiety. The students’ 25-minute play, titled “Overdrive,” even linked the increase in standardized testing since the No Child Left Behind era to rising youth suicide rates.

“Outside we are students, but inside we are patients,” one actor said. “They all think we’re sick, giving tests as medicine.”

Also touching on the perspectives of teachers who administer the tests, parents who trust teachers’ interpretation of test results, and policymakers calling for accountability, the play was commissioned by AERA President Amy Stuart Wells, a sociology and education professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, and served as the introduction to her speech on how testing is being used to perpetuate a separate and unequal education system for students of color.

“Scores on standardized tests are what it now means to be educated,” said Wells, who compared the education field’s reliance on standardized testing to using fossil fuels for energy — the subject of former Vice President Al Gore’s documentary. “This is the inconvenient truth of our education system.”

Wells, whose work has focused on desegregation, resegregation, detracking and charter schools, said after 30 years of measuring student outcomes through standardized tests, tests do more harm than good and “punish [students] for not knowing what someone who does not know them decides they need to know.”

She also said the education research community is complicit in continuing the mismatch between research and policy by using “big data and easy-to-crunch test scores.”

Then, she drew on research by civil rights lawyer and legal scholar Michelle Alexander, who has described the criminal justice system’s treatment of people of color in her book “The New Jim Crow.” Wells said the test score gap, teaching to the test score gap through “dumbing down the curriculum,” and discipline policies that exclude students from school are policies that target low-income communities of color and amount to a sort of “Jim Crow of education.”

Early in her career, Wells said she pushed for giving students of color more access to schools in white, middle-class neighborhoods because she assumed they were better schools. But she said those policies often take students out of schools where they have teachers of color who understand them and come from the same communities. She highlighted ethnic studies courses in states such as Oregon and California as progress toward considering students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences in how they learn.

Again referring to the push for sustainable sources of energy, as Democrats in Congress have proposed in the “Green New Deal,” Wells asked, “What is our educational new deal going to be?”

Examining the social and cultural aspects of assessment

Making assessment more culturally responsive was also addressed in a morning session — with the intentionally ambiguous title of “What Use Is Educational Assessment? Taking Stock and Looking Ahead” — where researchers previewed the articles in an upcoming journal published by both the American Academy of Political and Social Science and the National Academy of Education.

Taking both historical and forward-looking perspectives, the papers in the volume address both the risks of using standardized tests for accountability and placement decisions — especially at a time when the nation’s attention has been drawn to the college admissions scandal — as well as the potential for new developments in assessment to better reflect students’ social and cultural experiences.

“Policy is again at a crossroads, and smack in the middle of that intersection… is educational assessment,” Amy Berman, a deputy director at the National Academy of Education. On one hand, the Every Student Succeeds Act, she said, is in part a response to states and districts “contesting the federal role” in education, but on the other hand, there is still an “evidence movement” in policymaking and increasing advancements in technology’s role in assessment.

Michael Feuer, an education policy professor at the George Washington University and the dean of the Graduate School of Education and Human Development, said that separate papers by Eric Hanushek and Susanna Loeb, both of Stanford University, will present “fresh and stimulating perspectives,” including Hanushek’s argument about the connection between standardized test results and the health of a nation’s economy.

The session also included a discussion of how assessment can better take students’ unique characteristics and experiences into account — which is what the Denver Public Schools (DPS) is trying to do in partnership with the University of Colorado-Boulder (CU).

“We began with the premise is that all learning is cultural in nature,” said William Penuel, an education professor at CU. Working with Douglas Watkins, a high school science curriculum specialist with DPS, created 12 “sociocultural” survey questions for students taking 9th-grade biology, but then also interviewed them to increase the validity of the survey results to see if their answers really match what happens in the classroom. They also added three content-related questions about the biology lessons.

“Teachers really want evidence that this sociocultural stuff is real,” Watkins said, but added that they also need to know their students understand genetics and other units within the course. They found students did better on the three subject matter questions when they also answered the 12 questions.

Ultimately, Feuer said, the goal is to reach a level where the benefits of assessment outweigh the risks. He added that the joint publication brings together education researchers with those who study human behavior.

“What we’ve got here is evidence that behavior needs to become more relevant to the design of assessment,” he said, “as well as understanding the behavioral consequences of testing.”

The four-day school week that wasn't

In a roundtable session, Liz Hollingworth, an education professor at the University of Iowa, provided a case study on how not to push for a four-day school week. Studying a small rural district in Iowa, she followed the superintendent’s efforts to convince school board members to approve a four-day week, based on his belief that it would help the district better recruit and retain millennial teachers.

He formed his opinion, she said, because only two people applied for an open math teacher position. And the district’s only inquiry into the issue was a two-question survey. The first question asked teachers if they liked change and the second asked them if they would support a four-day week in order to recruit and retain younger teachers. Because over 90% of the teachers responded yes to the second question, “he thought he had this,” Hollingworth said.

Her review of the research on four-day weeks — which have been widely implemented in Oklahoma as a cost-saving measure — showed that arguments in favor include using the fifth day to give struggling students more instruction, giving older students opportunities for internships and part-time work, and using the day for athletics.

“The No. 1 problem is what you do with those kids on that day,” she said, adding that district leaders didn’t address concerns from board members about feeding students on free- or reduced-price lunch.

Ultimately, the board voted 3-2 against the plan. “The idea of kids not having food on the fifth day overrode everything,” Hollingworth said.

The case, however, also raises the issue that leaders in smaller, rural districts often lack the resources or knowledge of how to collect feedback from their community. Others in the session recommended that districts in such a position work in partnership with university researchers when considering such policy changes or that administrators in district leadership preparation programs conduct action research projects in such districts. Finally, Hollingworth suggested that the case points to the superintendent’s inability to build consensus.

“You never bring something to a vote,” she said, “if you don’t know what the votes are.”

Other significant research

Here are a few of the other studies receiving attention this year at AERA:

- In her review of the studies on students reading from screens, Virginia Clinton, an associate professor of education at the University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, finds that when compared to reading on paper, reading on a screen had negative effect on student performance. The paper that "readers may be more efficient and aware of their performance when reading from paper compared to screens."

- In a session on early-career teachers, five researchers presented papers highlighting what they're learning about new teachers entering the field. For example, as past research has suggested, beginning teachers are more likely than 20 years ago to work in schools with high percentages of low-income and minority students. Administrators and teacher educators tend to not be among the networks of educators that teachers say they are turning to for guidance and new teachers often struggle to form connections with veteran colleagues. They also frequently name someone other than their assigned mentor as the person they seek out for support. Finally, churn — changing schools or grade levels — does not appear to happen as much during a new teacher's career as it does among those with more years of experience.