Dive Brief:

-

Congressional leaders remained divided over the effectiveness and direction of the charter school movement, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and increased parental involvement in tailoring their children's education, during a Wednesday hearing of the House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education.

-

Lawmakers and witnesses were torn between bolstering charter school support on one hand and increasing oversight of existing charters while fortifying support for traditional public schools on the other.

-

Points of contention included whether charter schools have enough oversight due to substantial closure rates. Lawmakers also debated whether charters are effective and equitable alternatives to traditional public schools, considering that their admissions and discipline practices could disproportionately impact underserved students like students with disabilities or lower-performing students.

Dive Insight:

The debate comes amid the climbing popularity of charter schools.

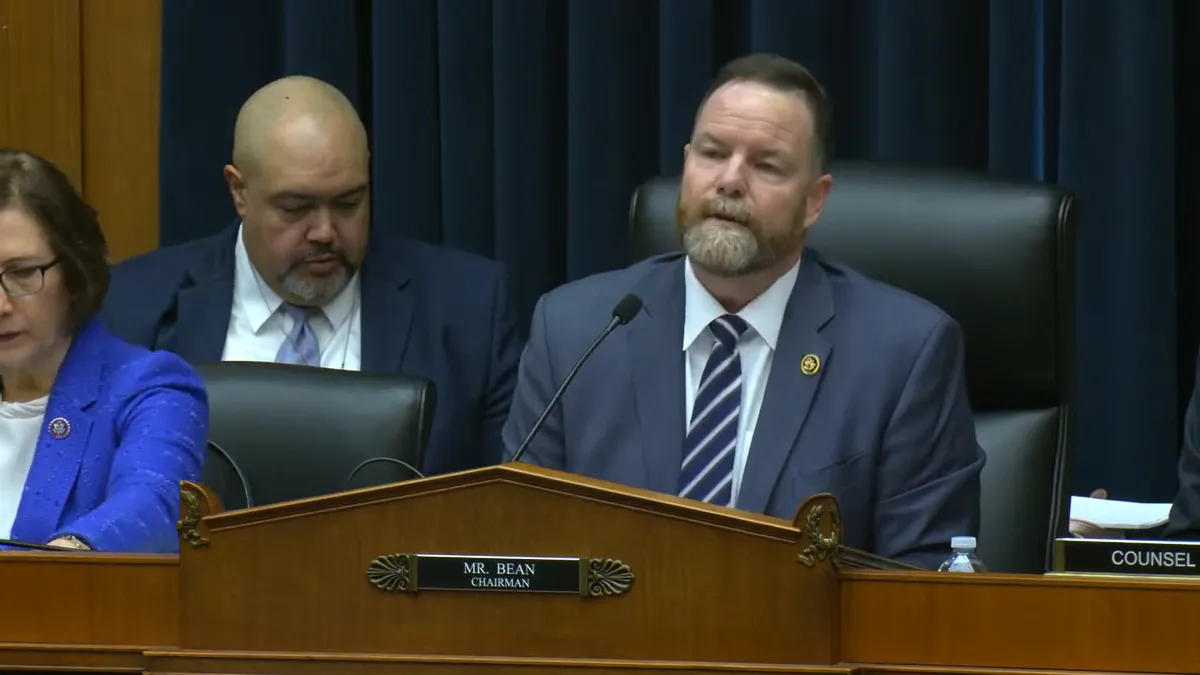

"Charter school growth is accelerating," said Rep. Aaron Bean, R- Fla., who is chair of the subcommittee. In fact, charter school enrollment continued to grow following the COVID pandemic, building on momentum gained from school building closures and distance learning, according to a 2023 report from Moody's Investors Service.

However, Democrats raised concerns about the rates of charter school closures and the performance of online charter schools.

Between 1999 and 2017, over a quarter of schools closed during their first five years of operation, and 40% had closed by the 10-year mark, according to a 2020 study by the Network for Public Education, a public education advocacy group.

Online charters, which gained popularity during the pandemic, had a lower percentage of students take state achievement tests. Those that did earned significantly lower scores than other school types, according to a 2022 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

The report also found that virtual charters may have "increased financial risks" because of hurdles in measuring attendance. It also suggested the U.S. Department of Education should intervene to help states address these two issues.

"But unfortunately, charter schools are not subject to the same level of oversight and accountability as traditional public schools," said Rep. Suzanne Bonamici, D-Ore., during the Wednesday hearing. "And as a result, we often do not know whether charter schools will provide students with any meaningful benefits."

However, Rep. Lisa McClain, R-Mich., said failing charter schools should receive additional funding and support.

"If a public school fails with less rules, less regulation — we just want more money to fix the problem," said McClain. "So if money is the answer for public schools, why wouldn't we give money to the answer for charter schools?"

A handful of representatives fell in the middle of the spectrum, supporting effective charter schools while also expressing the need to improve public schools so all students have equal opportunity to succeed.

"So why then are we not talking about making all schools the best that they can be, instead of picking off and creating subsets where a select handpicked group of students have access to high-quality specialized learning?" asked Rep. Jahana Hayes, D-Conn., who was named National Teacher of the Year in 2016.

Bean, at the conclusion of the hearing, agreed.

"We should keep trying to improve public schools, but we're gonna try to improve charter schools, too," he said.