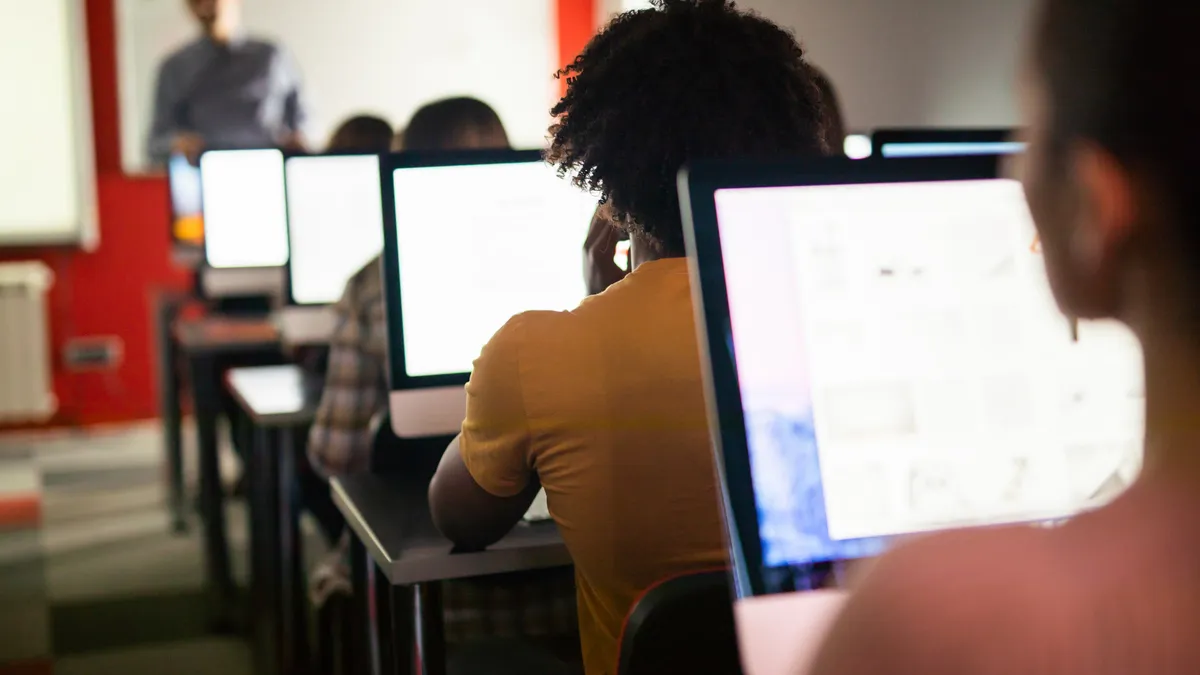

Fifth-graders in a classroom in Shanghai, China, are delving into the work of an 11th century poet, using artificial intelligence to spark a group project to generate their own poetry in a similar style. They have to agree on the ultimate outcome, developing and making edits, while the teacher is able to see the prompts each group is using — and their responses.

“It was a beautiful example of AI ‘infusion’ — kids using AI and having a collaborative experience,” said Julia Rafal-Baer, CEO and co-founder of ILO Group, a women-owned national education policy and strategy firm, who visited the classroom while attending the Digital Promise Global Cities Education Network Shanghai Symposium in November. “They didn’t teach AI literacy in an abstract way. The teacher had a whole discussion about, ‘What is the AI doing?’”

One student answered that question by saying AI was the teacher; another said teaching assistant.

“A third said, ‘We are now the teachers, and AI is the student,’” Rafal-Baer said. “Kids are getting what it will mean to work alongside AI and recognize that we are the ones who will have to drive AI.”

That jibed with what she heard that same week during a trip to a robot factory, where a question was posed about the most important skills the factory was seeking. “They didn’t even miss a beat: They said, ‘The ability to collaborate, alongside the technology,’” she added.

The experience in Shanghai prompted Rafal-Baer to reflect that the U.S. will need to strategize about the future of how AI will impact workforce skills and economic competitiveness, along with the appropriate ethical principles and guardrails. In China, she said, this is being done top-down, on a national level, but given the decentralized educational system in the U.S., states and local districts will need to be involved.

Overall, Rafal-Baer, who is also a former assistant commissioner of education in New York state and former special education teacher in the Bronx in New York City, sees the Chinese as being about a decade ahead in terms of AI implementation.

“The execution of large-scale national infrastructure around AI was quite staggering,” she said. “The difference isn’t just about AI as a tech tool, it’s about how they have brought artificial intelligence into a much more coherent operating system for everything they’re doing, and the development of infrastructure aligned with their values.”

Rafal-Baer would not suggest the U.S. should simply mimic China's approach, noting that the values, governance and level of surveillance behind their system would not go over well. But she believes the U.S. could follow China’s template in setting major goals to align its educational system with economic imperatives, use research to drive policy and practice, and develop technology that works in service of national needs.

Research and development divisions at China's universities "take national mandates and start to produce at scale,” she said. “They’re very transparent about sharing what’s working and what’s not working. Their labs are staffed with half engineers and scientists, and half educators. They have that intersection to continuously develop their products.”

At the classroom level, every teacher has an AI assistant to help with lesson planning, grading and professional development — not as a replacement for mentorship but to augment it, Rafal-Baer said. Every student has a portrait focused on proximal development — the space between what a student can do without support and what they cannot do even with support — and every course has knowledge graphs.

“AI isn’t just delivering content but helping to build systemic understanding,” she said. “Every school is part of a smart campus where there’s coordination, with so much data around the operations of the school.”

Given higher concerns about data, surveillance and privacy, not to mention centralized control, the U.S. is unlikely to simply copy this approach, Rafal-Baer said. But “we do need to get to a place where states are leading and protecting data while enabling strong structures,” she said. “So everyone knows how these models are working, and whether … they are leading to the outputs we want to see.”

Although the U.S. likely could not build the consensus for national coordination, given the importance placed on local control, that diversity allows for more creativity, Rafal-Baer believes.

“States play a really important role during this time to help set guardrails,” she said. States leading the way “to think about how to refine and design large-scale implementation feels like a much more appropriate way to think about this for our country.”