Circulating between the rows of desks, Marcelo Quiroz covers some guidelines to prepare the students in an Advanced Placement Environmental Science class for the workshops they will lead on topics such as deforestation and water deficits.

"OK, you're going to come up and tell us what we can expect from you next week," Quiroz instructs two students, who deliver some tips to their classmates on how to use less paper.

Modeled after a research conference, the assignment for these students at Summit Ranier in San Jose, California, is one of six major projects they'll complete in the course throughout the school year.

But it's also a critical milestone for Quiroz, a scientist trained in molecular biology who is entering the teaching profession through a new teacher residency program at Summit Public Schools (SPS) — a successful network of charter schools, backed by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, in California and Washington. A rigorous year of preparation, the new teacher preparation program is intended to train beginner educators to work specifically in personalized learning environments.

"It's definitely challenging," Quiroz said in an interview. The lesson he is leading in the classroom — including his planning process, the instructional strategies he is using, and how he will assess students — will also be part of a final presentation for the residency program.

While Quiroz worked as part of SPS's "tutoring corps," he said he wasn't really aware of the movement toward personalized learning and using data to guide each student’s learning.

"I'm still figuring that out," he said. "It's like an art form."

'Open to classrooms looking different'

When Pamela Lamcke, the residency's director, began thinking about the qualities she wanted to see in candidates for the program, a few key elements rose to the surface. First, she looks for people "who are open to classrooms looking different than what they might have experienced themselves," as well as those who are comfortable with students moving at their own pace, she said in an interview.

"The role of teacher is very different — more of a facilitator and coach than a lecturer," Lamcke said, adding that if someone is proud of being a “great orator,” he or she probably wouldn't thrive in a Summit school or any other personalized learning environment. She contrasts the residency program to the experience she had when she was learning to become a teacher.

"Most of my learning happened in a lecture," she said.

Summit residents, however, spend four days a week working with a cooperating teacher, who gradually gives the resident more responsibility for the classroom. By the end of the program, they will have "spent a year shadowing a really experienced teacher," Lamcke said.

Understanding the student experience

Teacher residency programs are increasingly viewed as more effective ways to prepare beginning educators — particularly those whose first classroom might be in a low-income school — in serving students with a range of academic and non-academic needs.

A 2016 report from the Learning Policy Institute noted that teacher residency programs bring more gender and racial diversity into the teaching profession, produce teachers who stay in the classroom longer, and may even lead to better learning outcomes for students.

Planning and implementing a lesson in a traditional classroom, however, is different than in a school where students’ assignments come from customized "playlists."

In its 2017 study of the Next Generation Learning Challenges initiative, the RAND Corp. suggested that finding the right fit between educators and schools with personalized learning models is an element for state and district leaders to keep in mind.

"Although it is not yet clear which qualifications are most important to consider when staffing [personalized learning] schools, having the flexibility to hire staff that support the school model, and fostering working conditions that support retention both seem important," the authors wrote.

They said teachers also need flexibility to try different instructional approaches, time to collaborate on curriculum, and support in choosing digital and non-digital materials.

Summit’s residency program is designed to mirror the format in which students attending Summit schools learn, which Lamcke said "helps them better understand the experience of their students and how to better support students in a personalized learning model."

While the first cohort of residents from the 2017-18 school year were trained to work in actual Summit sites, some residents in the current 2018-19 cohort were placed in "partner schools” in the Bay Area using the Summit Learning Program platform. Across the country, more than 380 schools have implemented the model. Some districts, however, have dropped the platform after giving it a try, with concerns over student privacy and some curriculum content, as well as the sense that personalized learning might not work for every student.

Lamcke said she didn’t know why some schools have decided to no longer partner with Summit, but that "working in a personalized learning model can be a shift in thinking for teachers at any point in their career." Summit provides coaching and professional development to teachers in partner schools. Lamcke added that Summit would also like to expand the residency program to other parts of the country.

Valuing personalization

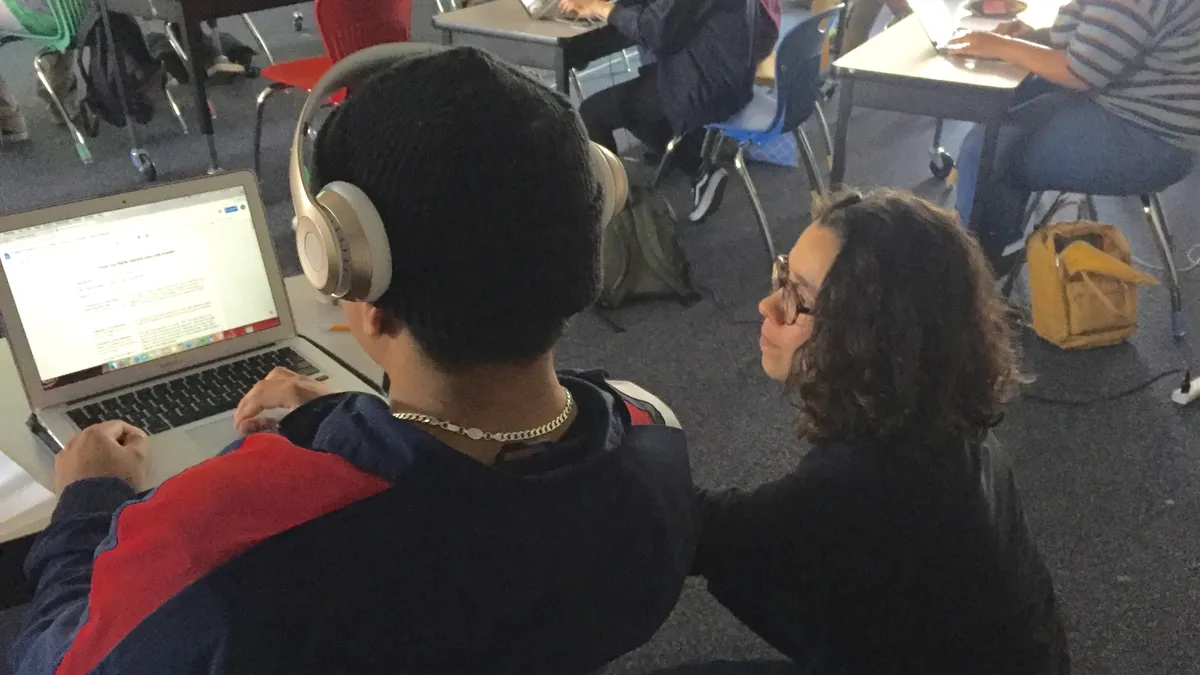

Quiroz's cooperating teacher, Marie Burns, stands off to the side of the classroom and lets Quiroz lead the whole-group activities.

"I was impressed with his classroom presence," she said, adding that she and Quiroz plan lessons together and have an informal debriefing session once a week. She's noticed, for example, that he needs more practice working with small groups, while also keeping the rest of the class occupied. Working with residents, she said, also benefits experienced teachers, adding, "I actually felt like I improved."

On Fridays, the cohort of 21 Summit residents meets at a conference center to take stock of each member's progress toward completing the residency and earning a preliminary California teaching credential.

The residents trickle in slowly. Many had a deadline to meet the night before that was tied to taking the Teacher Performance Assessment, or "edTPA," which is required for all teaching candidates in California. Molly Posner, an academic program manager with Summit, starts the morning by having residents write down any feelings of frustration they want to express, whether that's in essay or poetry form.

"You could just write down the words to your favorite break-up song," she says. Then, she has them crumple up what they wrote and throw it away — a symbolic act of clearing their minds and focusing on what they still need to complete. For the rest of the morning, they work individually and in groups to address remaining questions about their final projects.

Each resident also has a mentor, who might schedule an in-person meeting in these final weeks of the program for those who are falling behind on the list of tasks, like collecting artifacts of their teaching, preparing a video of their classroom, or explaining what they've done to engage parents.

"We're Summit; we really value personalization,” Posner says. "Different people are going to need different amounts of time."

Then the group breaks for lunch and gathers in the parking lot for “community-building” — essentially a lighthearted activity in which they stand in a circle and take turns trying to make each other laugh.

Teacher-student interactions

Like Quiroz, April Carrera — also a resident at Summit Ranier — moves through her Advanced Placement Government class always balancing a laptop in one hand. Today the 11th-graders she works with have been writing letters to the president on issues that matter to them. A time clock is posted on the screen at the front of the class to remind them how much time they have left to work.

Before the end of the day, she'll also oversee peers working together on essays, check in with students individually and meet with her 20 mentees — a group of students for which she has additional responsibility. Because she has grade-level meetings, she knows that many are still working to finish an English essay due that week.

“I know it's a lot on your plate, so just let me know how I can support you,” she tells them. She then stands by the open door of the portable classroom to briefly connect with each student as he or she leaves.

During mentor time, the students discuss steps they need to complete in preparing college applications, such as asking for letters of recommendation, researching colleges, and considering how they are going to spend their last summer before graduation.

“I really like how different the interactions are with the teacher and the student,” Carerra said. “I'm never sitting down.”