Among the most frequenly cited complaints from employers today is that the rising workforce is lacking soft skills, like problem solving and teamwork.

Recognizing this need, former teachers Anne Jones and Dan Gonzalez launched the nonprofit District C in North Carolina. The organization trains teachers to coach students on how to work together to solve real business problems, helps schools launch a course called “C Squad” and identifies business partners interested in participating.

The training follows lessons gleaned from Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmondson’s research on Google, which focuses on psychological safety in the workplace, as well as Carnegie Mellon University Associate Professor of Organizational Behavior and Theory Anita Williams Woolley’s work on collective intelligence.

Jones and Gonzalez compare students without the ability to problem-solve to basketball players who don’t take 3-pointer shots.

“In the 1980s, there were less than five 3-pointer shots taken per game,” Jones said. “Now, games average 32 3-pointers per game. Tall or short, you have to be able to take them because now it’s a 3-pointer game.”

Hiring managers report they are looking for students with team-building skills, she said. In fact, a Netquote survey found 42% of hiring managers are looking for candidates with problem-solving skills and 32% are looking for those who excel in communication. The duo concluded that after 16 years of time and investment in education, these students are graduating unprepared to function in business.

“Our point of view is that the game has changed,” she said. “But the education system continues to prepare two-point-shot-making players for what is now a 3-point economy.”

Community learning

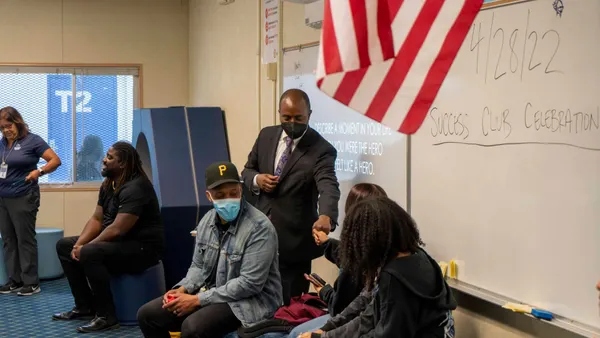

To teach problem solving, the couple (Jones and Gonzalez are also married) finds businesses with real problems and matches them with its District C schools.

The North Carolina Museum of History is among those that participated in the program and later implemented some of the suggestions.

At first, the museum’s problem appeared to be related storage. Its basement served as a staging area, but was also used to build and maintain exhibits. Unorganized and haphazard, the basement was a source of angst among many of the staff. Struggling to find a solution, the museum decided to outsource the problem to a group of students from Research Triangle High School in Raleigh, North Carolina, who were enrolled in a District C problem-solving course.

At first the students thought this was a piece of cake, said Jones.

“They thought the space could just be cleaned up and organized,” she said. “But after they dug into the problem, they realized there was something deeper going on.”

As it turned out, the museum’s basement problem was more about a lack of trust than of organization.

“At first, we thought there was an easy solution to the problem,” said senior Charanya Srinivasan. “Then we realized there were so many limitations to our solutions.”

Darshan Raj, another senior in the class, said the problems were multifaceted and ranged from marketing to efficiency.

“You have to be adaptive and encompass all the minute things,” he said. “There’s no one easy fix.”

The students suggested the museum respect the exhibiting routines and habits of the team and build trust by honoring some of the systems they already have in place. For example, students recommended implementing a tool-sharing magnetic placeholder system so everyone knows who used a tool last.

By offering these solutions, students bring real value back to the businesses, but are also getting authentic learning experience about real business problems, Jones said.

Suzy Lynch, a math teacher and one of the co-coaches at Research Triangle High School, was “blown away” by the way the students worked on the problems. “This gives students the soft skills they will need to go into the real world,” she said.

Ben Laptad, a biology teacher and District C co-coach, said the program allows students to take risks, be wrong and promote a growth mindset in themselves and others.

“This program increases access to real-world work situations,” he said. “The students are learning from their experiences and its an opportunity for all the kids. Each student, regardless of who they are or where they come from, will get something out of this that they can use to be better equipped for their future.”

District C isn't alone

While District C is working to expand beyond North Carolina, there are similar district-based approaches nationwide.

In Washington state, Washougal School District implemented a similar problem-solving program concept, but it’s flipped: Businesses instead go to the classroom. The class recently tackled a problem for a recipe-delivery business called Foodie In Training. Shipping the recipe boxes were eating up profits, but students in a wood manufacturing class helped the small business design a light-weight wood box that could keep costs down.

“The students looked at wood types and weights,” said Margaret Rice, director of career and technical education at Washougal School District. “They also saw the cost of labor was huge. If a box takes two hours to build and labor is $16 an hour, that will eat into your profits. That was the students’ ‘Aha’ moment.”

It’s important for students to understand how their work transitions to the workplace, Rice said.

“Anytime we connect students to businesses, good things will come from that,” Rice said. “It builds students’ confidence, because they are connecting with other adults rather than their teachers or parents.”

These programs also help dispel misconceptions about what is happening in high schools, she said.

“This gives the community a chance to see what students are doing and give feedback,” Rice said. “The networking that happens for students and employers is never a bad thing. They get problem-solving experience that is relevant to what is happening, and businesses get different perspectives when they take a risk to put their problems in the hands of students and see what they can do.”