This is part one of a two-part series on the 50th anniversary of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. For part two, click here.

When Antoinette Banks' daughter, Nevaeh, was diagnosed with intellectual disabilities in 2011, Banks was told her 5-year-old daughter would have a 0% chance of living independently as an adult.

"What I'm hearing is that my kid doesn't have a future," Banks says. "It broke me for a little bit."

To fill in all the unanswered questions she had about her daughter's future, Banks began trying to better understand the special education system she and her daughter were now a part of.

Just understanding all the processes and paperwork — individualized education programs, evaluations, assessments, procedural notices and more — got "super confusing sometimes," says Banks, who lives in Sacramento, California.

Even after she filed all the special education documents in a three-ring binder, Banks still struggled to organize documents critical for monitoring the interventions provided by multiple teachers and therapists, as well as for tracking information from doctors and diagnosticians.

She created what she called an online "spreadsheet on steroids" to share with her daughter's support teams. As she improved her homemade tool, she began sharing the template with other families in similar situations.

That prototype evolved into Expert IEP, a platform that's now powered by artificial intelligence to help families, school districts, therapists and doctors collaborate on services for children with disabilities, Banks says.

"I thought that if I could get everyone to just communicate with one another and not be so siloed and not telling me what they think, but what does the data say about my daughter, then maybe we can get focused on what she actually needs in her learning environment," Banks says.

Fast forward to today: Banks' daughter is 19 years old and graduated in June from a public California high school with a general education diploma. Nevaeh is now studying biological systems engineering at a northern California college and wants to become a nanotechnologist, according to her mother.

"I feel so very, very blessed to have been able to be on this wild roller coaster ride with my daughter and continue to advocate and refine, because anything is possible," Banks says.

The tool Banks created — which she said was born out of both frustration and necessity — is but one example of the many tools and techniques developed over the past five decades to support students with disabilities and their families and teachers.

On Nov. 29, the landmark Individuals with Disabilities Education Act turns 50. President Gerald Ford signed the legislation, originally known as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, guaranteeing students with disabilities the right to a free and appropriate public education. Before then, no federal requirement existed that schools must educate students with disabilities.

In addition to opening public schools to a whole population of children, the law became the catalyst for legions of innovative practices and tools cultivated from both public and private sources. The transformations, special education experts say, were spurred by an ongoing need to individualize student supports while helping children with disabilities progress in general education classrooms.

IDEA eligibility grows over 5 decades

Many of these practices and technologies — such as universal design for learning, assistive technology, and positive behavioral interventions and supports — would not only be proven to help students with disabilities, but also to benefit their peers without disabilities.

Innovative and proven practices that are effective for a student with disabilities are "going to work with a student without disabilities," says Lindsay Kubatzky, director of policy and advocacy for the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

To mark IDEA's 50th anniversary, K-12 Dive spoke with special education experts about approaches, practices and technologies that have revolutionized how students with disabilities are supported — and how these innovations keep evolving.

Eliminating learning barriers with UDL

Delana Robles spends her day problem solving. As the universal design for learning resource teacher in New Mexico's Albuquerque Public Schools, Robles helps teachers make learning accessible for students who have dyslexia, hearing or vision impairments, learning disabilities or other conditions.

"UDL is a way to include every student in the classroom by looking at who they are as a learner and as a person, versus seeing them as someone with a deficit," Robles says. If educators understand each student's strengths and needs and how to support them, "education will improve across the board," she says.

The UDL framework can be applied across all ages and learning environments to reduce instructional barriers through classroom design, assistive technology and engaging teaching and learning practices. These could include using text-to-speech features or large fonts, or allowing students to choose how they demonstrate their knowledge by writing a report, creating a slideshow or performing a skit, for example.

UDL got its start in 1984 when neuroscience researchers were looking for ways computers — which were just becoming more widely used for personal and professional use — could improve learning for students with disabilities. A group of five clinicians from North Shore Children’s Hospital in Salem, Massachusetts, formed the nonprofit Center for Applied Special Technology.

Lindsay Jones, CEO of CAST and former president and CEO of the National Center for Learning Disabilities, says one of the biggest developments in special education over the past 50 years has been the acceptance of learner variability — the idea that each student processes and demonstrates learning differently. UDL, Jones says, helps schools use technology, classroom designs and instructional practices to make learning more effective and inclusive for each student.

Jones calls UDL "future proof," meaning demand will only grow to customize learning so as to propel student understanding, engagement and agency. "I think it's exciting that special education has driven a lot of the research that's impacted all of education," she says.

Making reading accessible through Bookshare

Obtaining books in accessible formats for students who have low vision or are blind used to be a slow and laborious process. Schools typically had to manually request large-print or Braille editions that could take weeks or months to arrive.

In some cases, schools could track down the limited number of large-print or Braille copies that existed. Schools in rural areas faced even greater barriers to obtaining accessible books, according to historical accounts. And when obtained, these books were big and heavy for students to carry around.

Schools also relied on staff or volunteers to make audio recordings of entire books — another time-consuming process.

All this meant that students rarely got the accessible content in time to participate in learning along with their peers, and that delay impacted their learning outcomes.

But as technology evolved, and as the 1997 reauthorization of IDEA required schools to consider assistive technology for every student with disabilities, schools became more equipped to serve students who had difficulty processing or comprehending printed words.

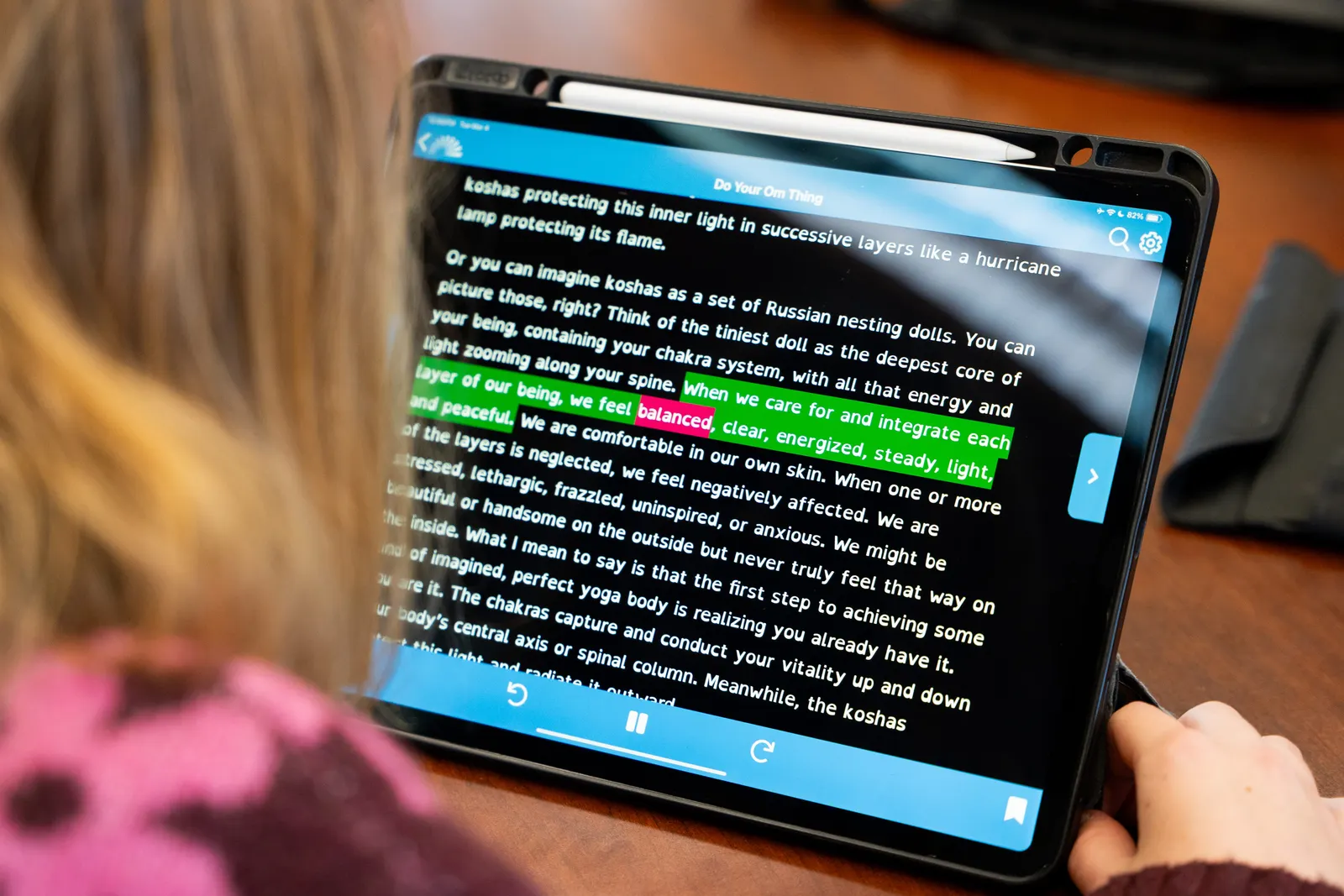

One tool that opened access to learning for students with disabilities is Bookshare. The free repository of titles allows students to customize how they see or hear text on a screen and to physically manage how to flip pages on reading devices.

It's the world's largest library of audio and ebooks — with 1.4 million titles, according to the organization. And access is free for qualifying U.S. students in public, private and home schooling because it is supported through grants from the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Special Education Programs. In fiscal year 2025, OSEP awarded $9 million to Bookshare.

Part of Benetech, a nonprofit software organization focused on improving accessibility, Bookshare is the largest distributor of accessible textbooks in America. It operates through the National Instructional Materials Access Center, a federally funded, searchable online repository of source files for K-12 instructional materials that was created through the 2004 reauthorization of IDEA.

For schools, this means educators can request an accessible book for anyone from an early elementary school student who is struggling with decoding, to a high schooler who is blind and studying for Advanced Placement exams. Bookshare is also free for qualifying students in postsecondary, graduate, vocational and continuing education classes.

Ayan Kishore, Benetech CEO, says giving pre-K-12 students access to Bookshare materials helps put them on a pathway for postsecondary success and beyond.

"Bookshare started because we zoomed into a huge challenge. There are many challenges, but one challenge is accessibility," he says. "The books that are used in a classroom are just simply not accessible for someone who is blind or dyslexic or has other sorts of disabilities."

Guidance issued by the Education Department in January 2024 urges schools to consider an array of assistive technologies for students with disabilities. These include text-to-speech software, word prediction devices to help with writing and communication, augmentative and alternative communication devices, and visual schedules and timers. Low tech tools, such as pencil grips and modified scissors are also encouraged to remove barriers to learning.

I think it's exciting that special education has driven a lot of the research that's impacted all of education.

Lindsay Jones

CEO of CAST

Rebecca Thomas, a coach at New Mexico UDL, a state-funded grant program, helps teachers remove barriers to learning. Bookshare, assistive technology and UDL approaches are helping drive student engagement and close learning gaps through accessible tools, she says.

Supporting teachers in their jobs is also core to New Mexico UDL's mission. "We love finding new tools that will help take things off teachers' plates," Thomas says.

Kishore says Bookshare keeps evolving. Several years ago that meant adding accessible STEM content. Now in development is Bookshare Plus, which aims to use AI to make any educational content — such as classroom handouts and worksheets — accessible.

Nonetheless, the future of Bookshare, which is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, is tenuous. President Donald Trump's FY 2026 request would cut all funding for the Education Department's Education Technology, Media, and Materials for Individuals with Disabilities program under IDEA, which provides accessibility technology and services for students with disabilities. Rather, the proposed budget recommends states use Part B grants to set their own priorities for special education spending.

Earlier this month, after a prolonged federal government budget impasse and shutdown, Congress agreed to a continuing resolution to fund the Education Department through Jan. 30, 2026, at fiscal year 2025 funding levels.

Addressing student needs through teletherapy

When Missouri's Carthage Intermediate Center's only speech-language pathologist moved away in 2023, the grade 4-5 school in the Carthage R-9 School District struggled to find a replacement who could support students whose IEPs required speech and language interventions.

Then, the next year, the center's two feeder elementary schools lost their speech-language pathologists, too. The void — which couldn't easily be filled because of a shortage of these specialists in the area — led the three schools to use teletherapy to supplement their services, says Susan Hatcher, assistant principal of Carthage Intermediate Center.

During online asynchronous sessions, a remote speech-language pathologist works 1-to-1 or with small groups of students on their communication skills while an in-person paraprofessional keeps them on task.

"We've got lots of examples of where kids have just really done well with this particular service and have really made some great growth," says Hatcher.

Teletherapy, which began in the medical field, has allowed school districts, particularly in rural areas, to provide student services in the face of significant shortages of special education and related service providers.

Exact numbers are difficult to pin down on how many schools or students are taking this route. But several teletherapy platforms, including Presence, eLuma and Parallel Learning are working directly with school districts.

Presence alone has delivered more than 7 million teletherapy sessions to partner schools since its founding in 2009, according to the company. The company works with about 10,000 public, charter, private and virtual schools.

Bonnie Contreras, senior director of clinical solution engineering at Presence and a former school counselor, says that while the vast majority of students do well with the virtual interaction, it is not a replacement for special education teachers and other in-person experts.

"At the end of the day, the goal is for the student to really thrive with the resources that they need to do their best," she says.

Hatcher says the district "would have been holding out hope" to attract and hire a qualified speech-language expert. The schools might have been able to partner with neighboring districts to share a provider, she says. But in the worst case scenario, a lack of available services would have required the schools to provide compensatory services or additional interventions, which can be costly, she adds.

While more in-person speech-language pathologists would be ideal, teletherapy allows the flexibility and customization to provide services to students when and how they need them, Hatcher says. In the end, these services are "very individualized, which, of course, is very much the spirit of IDEA."

Supporting learning through PBIS

Would you punish a student for failing a math test?

That's the question Timothy Lewis asks people when he explains how positive behavioral interventions and supports in a school can be just as vital as academic interventions and supports.

If a student failed a math test, educators might review the material, organize learning supports and monitor the student's progress, Lewis says. But when he began working with students and young adults with challenging behaviors as a special educator in the 1980s, the common approach was to discipline students for disruptive behaviors.

Lewis, director of the University of Missouri Center for School-wide Positive Behavior Support and a professor of special education, wanted to find a way to avoid punitive approaches and increase students’ academic performances by teaching appropriate and expected behaviors.

"Here's the key about behavior," Lewis says. "Behavior is functionally related to the teaching environment, meaning kids do behaviors because they can predict outcomes. And if you're a really good teacher, you set up your environment to increase the likelihood kids learn."

Positive behavioral interventions and supports got their origins in the late 1980s from researchers like Lewis, along with George Sugai, Robert Horner and others at the University of Oregon. Their work on PBIS evolved from research on improving student behavior supports not just for individual students, but for entire classrooms and schools.

PBIS is built on a multi-tiered system of supports where all students gain an understanding of classroom and school expectations and appropriate social, emotional, and behavioral skills. Interventions intensify for the students who need more individualized supports.

Nearly 27,800 schools in the U.S. used PBIS in 2024, according to the Center on PBIS, a technical assistance center that began in 1998 and is funded through federal grants from OSEP and the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education.

PBIS practices contributed to improved attendance, teacher retention, and English and math achievement, along with reduced substance abuse and bullying, according to various research.

For instance, students with and without disabilities attending Missouri schools with universal PBIS showed better attendance, and students with disabilities spent more time in a general education classroom, than students at schools without PBIS, according to a report from the 2022-23 school year published by the Missouri Schoolwide Positive Behavior Support team. Moreover, schools with high levels of PBIS implementation over time showed more positive outcomes for both students with and without disabilities.

PBIS can also lead to cost savings. For every dollar spent on implementing PBIS schoolwide, about $105 is saved through decreased suspensions that also reduce dropout rates, according to a 2017 report published by the federal PBIS technical assistance center.

"PBIS is probably the most researched and has probably some of the best gold standard research to show its effectiveness of anything out there, and OSEP supported that," says Larry Wexler, a longtime former director of research to practice at OSEP.

Lewis says the PBIS work, through the national center and statewide programs, keeps evolving. The PBIS framework in schools has been used to address school crisis situations, opioid addiction, mental well-being and other challenges. In terms of scope, it has been implemented in everything from a one-room K-12 school to large urban schools, he says.

"No one in education can make kids behave, nor can we make them learn. It's all about building an environment to increase the likelihood" of learning for students with and without disabilities, Lewis says.

Visuals Editor Shaun Lucas contributed photo support to this story.