A proposed change to how states measure racial disparities in special education for federal data collection could limit transparency and make the issue harder to identify, according to public comments.

In August, the U.S. Department of Education sought comments on the possible elimination of a data collection within states' annual applications for Part B grants under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

Those applications give assurances that the state and its districts will comply with IDEA rules as a condition for receiving federal IDEA funding. Currently, those applications ask states to provide rationale and supporting data if they want to alter the metrics they use for how they identify districts and schools with racial disparities in student special education identifications, placements and discipline.

The data collection for racial overrepresentation or underrepresentation in special education — known as significant disproportionality — helps states and districts identify disparities so they can address the causes and find remedies.

The Education Department is not proposing to rescind or pause the significant disproportionality regulation, a rule known as Equity in IDEA. But the agency said in its public notice seeking comments that it wants to reduce paperwork burdens by eliminating this part of the data submission from states. The comment period ended Oct. 21.

The agency estimated that the annual data collection takes 14 hours per state or territory and costs about $26,880 collectively.

States would still need to comply with the Equity in IDEA rule, they just wouldn't have to update the Education Department with the changes they make to how they measure significant disproportionality.

But opponents of the change said it would limit the public's ability to make sure districts are tracking and responding to racial disparities in special education.

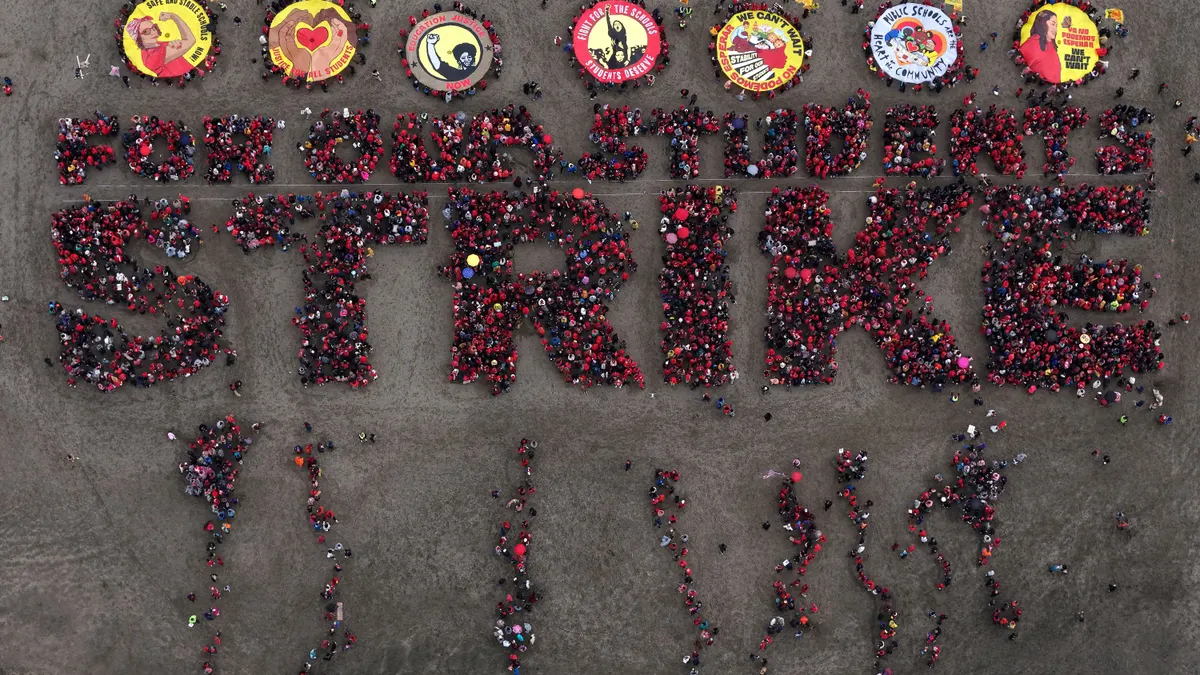

Students with disabilities, for instance, have higher rates of in-school suspensions, federal data has shown. Although students with disabilities represented 17% of K-12 student enrollment in the 2021-22 school year, they comprised 27% of students with one or more in-school suspensions, 29% of those with one or more out-of-school suspensions, and 24% of those who were expelled, according to the Civil Rights Data Collection.

Transparency and equity concerns

"Eliminating the currently required public reporting of this data simply obfuscates the data from governmental and public scrutiny," wrote the Office for Civil Rights Alumni Collective. The collective is a group of former career attorneys and managers in the Education Department’s civil rights arm.

In its Oct. 16 letter commenting on the proposed change, the collective said its members had investigated and resolved hundreds of complaints and compliance reviews that found states and school districts to have disproportionately high rates of students from particular racial or ethnic groups identified as having disabilities, placed in restrictive settings, or subjected to discipline.

"The data on disproportionality collected under the IDEA was an essential part of this work," the letter said.

Jennifer McKinnish, a parent and the Nevada State Chair of the National Council on Severe Autism’s National Grassroots Network, wrote in a Sept. 3 comment that collecting and reporting equity data is "often the only tool we have to prove when our children are being mistreated, misidentified, or pushed out of the classroom."

McKinnish added, "Without tracking, those inequities will not only persist but will become invisible."

Daniel Losen has studied significant disproportionality in special education for several decades as a researcher and is the senior director of education for the National Center for Youth Law. In an Oct. 21 letter, Losen said the proposed change would undermine transparency of federal oversight.

The Education Department, he wrote, "would not be able to provide sufficient oversight when and if state governments made substantial changes to how they identify problematic disproportionality."

His letter cited research from the U.S. Government Accountability Office, published in 2013, that showed some states' definitions of racial overrepresentation in special education made it unlikely that any of their districts would be identified for significant disproportionality. GAO found that in 2010, about 2% of districts — or 356 districts in 29 states — were identified with overrepresentation in special education.

The Equity in IDEA regulations in 2016 required all states to adopt a standard method for measuring significant disproportionality but allowed each state to set thresholds for monitoring the racial disproportionality of their districts. By the 2020-21 school year, about 5% of districts — or 825 districts in 39 states — were identified as having significant disproportionality.

By eliminating the reporting data, "the proposed change would gut future federal oversight, which, over time, would have nearly the same impact as eliminating the 2016 regulations," Losen said.