While ninth-graders across the country are taking biology or Earth science, virtually every student in Trenton, NJ, is tackling physics. It’s a required freshman-year course in the city's public schools. And even though districts in other states would have trouble finding enough qualified physics teachers to make such a change possible, Trenton benefits from the nearby New Jersey Center for Teaching & Learning, the No. 1 producer of physics teachers in the country.

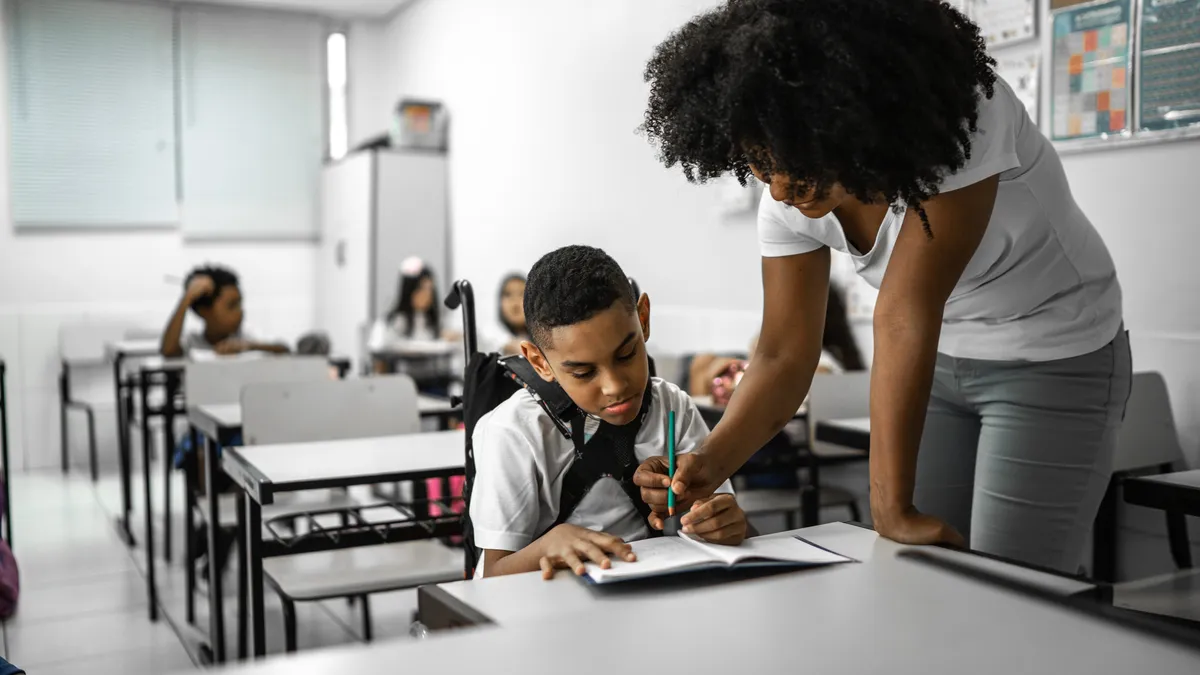

The NJCTL has trained 25 of Trenton’s teachers to be physics instructors, operating under the philosophy that teaching is harder than physics. It takes certified teachers of any subject and capitalizes on their existing expertise in understanding students, giving them lesson plans, curriculum materials and assessments for an algebra-based Physics course that can lead directly into AP Physics.

“If you get someone who knows physics, but they can’t get a group of kids to move forward together, then it doesn’t really matter that they know physics,” said Bob Goodman, NJCTL’s executive director and creator of its physics teaching model. Goodman got a bachelor’s degree in physics from MIT and believes the subject is a critical building block for further scientific inquiry.

It also happens to be interesting and engaging for students.

Goodman developed an algebra-based physics course for students at Bergen County Technical School in New Jersey while he was a teacher there. He found projects like figuring out how to launch a rocket interested students more than a sheet of math equations, even though they would need to use those same equations to get the rocket off the ground.

Goodman’s students — generally lower-performing, academically — quickly improved their math skills, and, by working in groups, they helped each other fill gaps in their knowledge. What’s more, the ninth grade course reached students of both genders before the girls could be dissuaded from physics, leading more of them to choose AP Physics as a follow-up course than average.

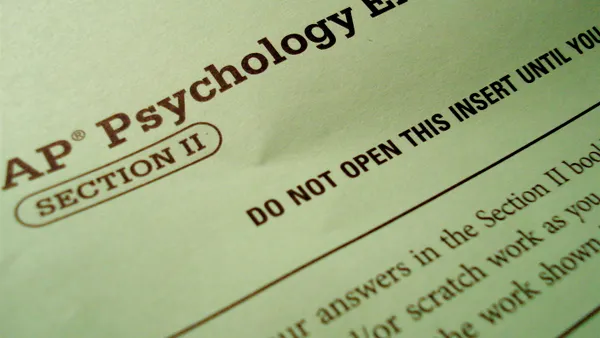

Girls in schools teaching to the NJCTL’s Progressive Science Initiative were 5 times more likely to take the AP Physics B exam in 2014 than their peers across the United States. Black students in these schools took AP Physics at almost 11 times the rate as black students elsewhere, and they passed the exams at 3.4 times the rate. Likewise, Latino students taught through the program are 7.4 times as likely to take AP Physics and 5 times as likely to pass the exams.

Perhaps more important than the NJCTL’s progress with students, however, is its progress with teachers. There are only about 5,000 students per year graduating with physics degrees from the nation’s colleges — the pool from which high school physics teachers are generally drawn.

Brigham Young University claimed to produce more high school physics teachers than any other department in the country in 2013. It graduated 14. That same year, Goodman says the NJCTL produced almost 40. And unlike the physics majors coming out of college departments who are predominantly white or Asian and male, 48% of NJCTL’s physics teachers are women and a large number are black or Latino.

In Trenton, Michael Tofte, supervisor for K-12 STEM instruction, has become an advocate of the Progressive Science Initiative teaching model.

“I think that the strength of the program is in its formative assessment use and constantly acquiring student data and using that to drive instruction,” Tofte said.

Embedded in every day’s class presentations are questions that teachers can ask of students to gauge their understanding before moving on. The NJCTL recommends schools purchase smart projectors and electronic responders so students can answer survey questions and teachers can keep that data. Its materials for teachers also include hundreds of formative assessment problems, and Tofte appreciates a focus on allowing students to retake tests they fail.

“That encourages students to continue learning and continue trying to learn the material,” Tofte said.

To teach Goodman’s ninth grade physics course, instructors go through an intensive summer program where they take the entire course and learn the material. Then, the following school year, teachers lead the first-year course while continuing their training program to learn how to teach AP physics. By the time they are ready to take the certification exam, teacher participants have 300 hours of classroom time and 150 hours of field experience teaching the first-year course.

And based on an analysis of people taking the Praxis exam to teach high school physics, NJCTL participants are just as likely to pass as others — even without an undergraduate degree in physics.

According to the latest Civil Rights Data Collection survey, fewer than half of all high schools with high black and Latino enrollments offer physics. The NJCTL program has gotten more physics teachers into urban schools, and it plans to expand its reach with an online teacher training course through Colorado State University-Global Campus, but a single program can only do so much. For every ninth grader in the country to take physics instead of biology, Goodman says schools would have to hire 35,000 more physics teachers.

Maybe that should be the goal.

The nation is becoming preoccupied with offering STEM opportunities to students, but Goodman says short camps and after school clubs are not going to prepare students for an engineering career.

“There is a pyramid to all of this,” Goodman said. “If you can’t do math you can’t be a scientist or engineer. Physics is the next step up.”