Playing at school, it turns out, is not as simple as it sounds.

Many children today are uncertain of what to play or how to initiate and end games. Conflicts arise about rules and who are the winners. The pandemic, educators say, stunted young children's natural play development.

As a result, educators, pediatricians and play advocates are encouraging schools to be more mindful and intentional about positive student-led play experiences at schools. They cite academic, physical, social and emotional benefits for kids when there is dedicated time for healthy, inclusive and safe play.

According to the National Association of State Boards of Education, nine states — Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Missouri, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Virginia and West Virginia — require daily recess for students. Each state has different policies for duration and the grade levels covered.

Starting next school year, California public schools will be required to provide at least 30 minutes of recess to elementary students, under a law passed in 2023. Recess, the law says, should be held outdoors when weather and air quality permits.

The average length of play at schools is 25 minutes daily, according to a 2018 survey of 500 elementary school teachers conducted by Wakefield Research on behalf of the International Play Equipment Manufacturers Association, a playground safety certification organization, and its Voice of Play, a nonprofit that aims to increase education about the benefits of play. All of the teachers surveyed said recess is essential to young children's mental and physical development.

Dr. Arwa Nasir, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine, said play at school is not a frivolous activity.

"It is the means by which children learn about their environment, develop their social skills and emotional regulation skills, and is really necessary as a restorative and regenerative activity after the child — or the adult for that matter — have engaged in mentally or cognitively challenging tasks," said Nasir, who is also chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health.

Play is also an innate activity for children. "Children will play if you let them and only will not play if you prevent them," Nasir said.

So why is play at school so difficult?

Rock, Paper, Scissors

Pandemic-related school closures and social distancing, playtime replaced by screen time, and school schedules squeezed in favor of academics are all blamed for a demise in both natural play and recess time, experts said.

At Marcy Arts Elementary School in Minneapolis, teachers and administrators noticed a few years ago — when the school reopened to in-person learning after COVID-19-related closures — that some students had significant gaps in how to interact in a play setting with other students, said Assistant Principal Jessica Driscoll.

Last year's 5th graders, for example, had not had an uninterrupted school year since they were 1st graders. In Minneapolis, not only did the community struggle with COVID, but there had been civil unrest following George Floyd's murder and ongoing police-community tensions in that city.

Additionally, a teacher strike shut down schools for three weeks in early 2022.

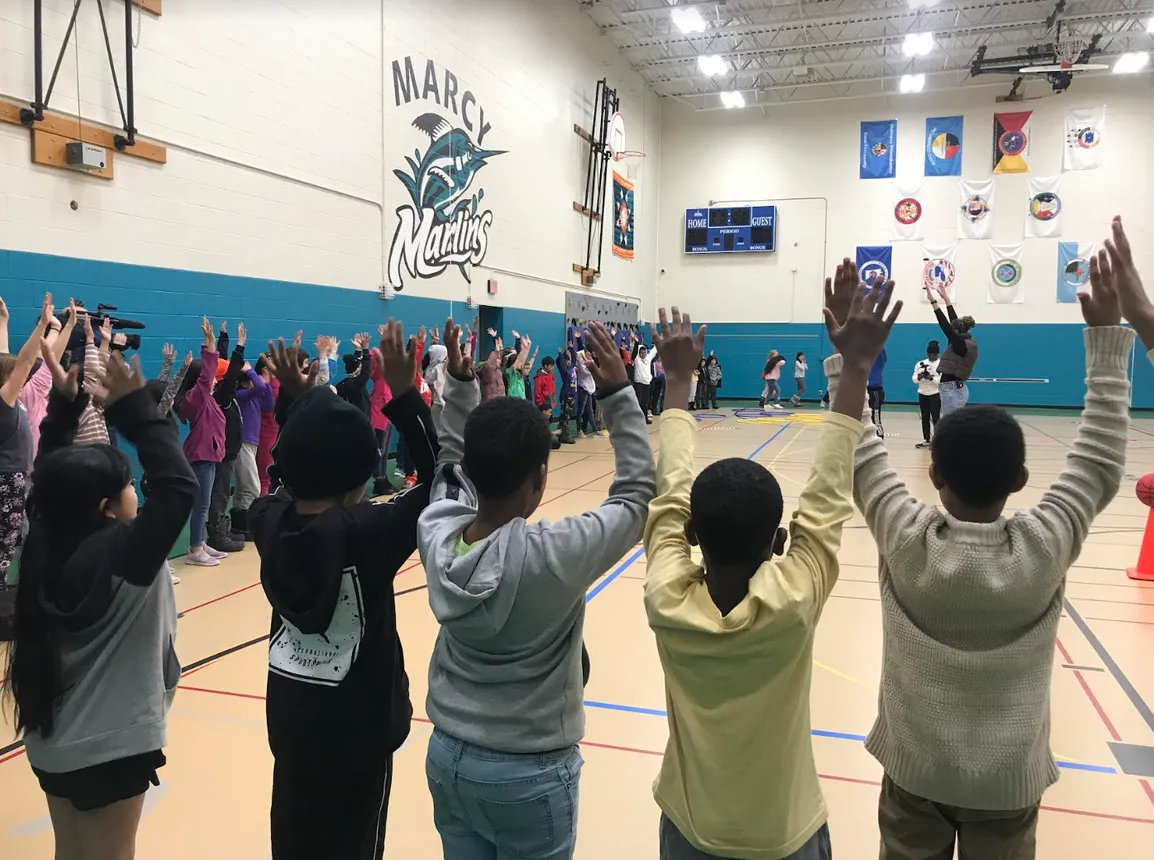

To fix its struggles around play, Marcy Elementary, which has 480 students in pre-K through grade 5, partnered several years ago with Playworks, a nonprofit that works with elementary and K-8 schools across the country to improve play and recess time. Playworks has provided professional development coaches to coach educators in observing children at play to better understand each child's strengths and needs.

The organization has helped Marcy Elementary implement routines for transitions to and from playtime. It has also suggested recess activities that support both physical health and social and emotional learning.

One of the most helpful recommendations Playworks provided was to use Rock, Paper, Scissors to settle playground conflicts, Driscoll said. That strategy even seeped into other school settings to resolve disputes between students, such as who gets to go first in the lunch line, she said.

The focus on playtime has also led to academic and social benefits at the school. When a group of kindergartners struggled academically at the beginning of this school year, educators decided to give them a 20-minute recess before school work even began in the morning. The students, Driscoll said, just needed to move a little bit before going to the classroom.

After a few months, data showed "tremendous growth" from fall to winter in these students' foundational reading skills, said Driscoll, who also credited other interventions for the gains.

"I love to go out there and throw around the football, because they [the students] are so shocked that a 5-foot-tall woman can throw a spiral."

Jessica Driscoll

Assistant principal, Marcy Arts Elementary School

The assistant principal noted other benefits from the attention on play. For instance, Driscoll said, play has helped create a welcoming environment for newcomer students who are English learners. Students of all backgrounds have bonded over student-led soccer activities, she said.

"If we have kids who are struggling to engage with each other in a productive way, or are struggling to do any sort of cooperative learning, any sort of navigating relationships in the classroom, one of the quickest and most effective ways to build a classroom community is to engage in collective play," said Driscoll.

Her personal favorite recess game, she said, is 500, a ball game with one thrower and several catchers.

"I love to go out there and throw around the football, because they [the students] are so shocked that a 5-foot-tall woman can throw a spiral."

Teachers need to get in the game

The American Academy of Pediatrics is currently updating its 2018 statement on the Power of Play, Nasir said. While that statement is directed toward pediatricians, many of the same principles apply to others who care for children, she said.

In fact, at conferences for pediatric professionals, doctors will discuss the need to give parents "prescriptions" to play with their children of all ages, Nasir said.

"Play is a very natural thing," Nasir said. "We actually kind of took it away from the children by tightly structuring their day. And now we really realize that we have to give it back to them."

Elizabeth Cushing, CEO of Playworks, said teachers want to integrate play into the school day in a way that is productive for everyone, including students with behavioral challenges and those with disabilities. The organization has a free tool that helps schools analyze ways they can improve recess.

"The first thing that we see that makes a difference is when adults get in the game alongside the kids," Cushing said. That signals to students that play is important. Teachers can also model positive play norms, such as high-fiving others, taking turns and recovering after a disappointing game, she said.

"The modeling of that resilience and that acceptance of the kind of give-and-take of play is a really important lesson too," she said.

Playworks emphasizes that kids should have games to choose from — but that they should also have agency to pick a game they want to participate in. The organization recommends having a routine for transitions to and from play, such as a call-and-response where everyone acknowledges a start and finish to the recess period.

"It's amazing how rituals like that, especially when you use play to do them, can make the whole school day go better.”