This latest Pre-to-3 column focuses on a family literacy and resilience initiative that began in rural Tennessee but is now expanding to an urban setting in New York City. Past installments of Pre-to-3 can be found here.

Since 2012, families in Grundy County, Tennessee — northwest of Chattanooga — have been learning about lesser-known treasures in their rural community in partnership with the Yale Child Study Center, Scholastic and Sewanee: The University of the South.

Discover Together Grundy is a place-based, early literacy and family resilience initiative that aims to build stronger connections between families as they learn and share the stories that surround them. Through a parent co-op for young children, a summer camp and an after-school program, the children and their families begin to take pride in the place they call home.

“This is one of the most naturally beautiful areas in the state,” Dr. Linda Mayes, a psychiatry, pediatrics and psychology professor at Yale — who graduated from Sewanee — said in an interview. “Through grounding a curriculum in your place, the families are starting to learn about their own backyard.”

Now, the leaders of an early-childhood initiative in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, are hoping to bring those same experiences to families in an urban setting.

“The residents are so eager to be involved in decision making and the allocation of resources in this community,” Kassa Belay, the co-director of collective impact at SCO Family of Services, a New York City social services agency, said in an interview. Belay co-directs United for Brownsville with David Harrington of Community Solutions, a nonprofit focusing on solutions to homelessness.

While the daily lives of families in Grundy County are quite different from those who ride the 3 train in Brooklyn, Harrington said they share similar challenges, such as a sense of social isolation and feeling like they don’t have places in the community to enjoy as a family, or opportunities for their children.

“The specifics might be different,” Harrington said in an interview. “But the underlying concerns are the same.”

'Changing the narrative’

As part of a “participatory planning” process, Harrington and Belay learned parents and others in the community have “an appetite for changing the narrative about Brownsville,” a predominantly black and Hispanic neighborhood where life expectancy is 11 years less than it is in the city’s financial district, more than a quarter of adults have not completed high school and rental units are more likely to be poorly maintained, according to a 2015 Community Health Profile.

The co-directors also learned families especially lacked structured opportunities for young children on the weekends.

“It hits home to me when I hear families say, ‘I don’t have safe, supportive things to do in this community,’” said Harrington. The father of a toddler son, he described the “great networks” available to families in his Brooklyn neighborhood of Park Slope and said he hopes Discover Together will create similar connections for Brownsville families.

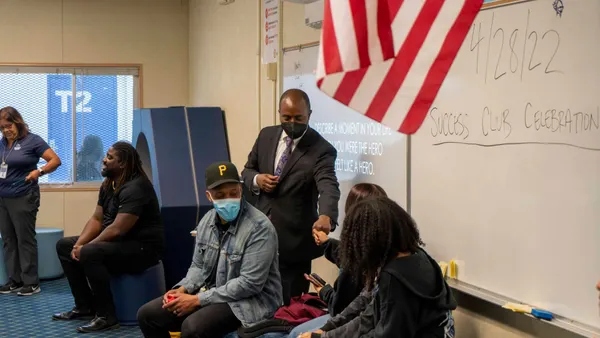

That’s why Discover Together’s parent co-op program is the first component of the model they plan to implement this fall in two sites — a SCO-run licensed child care center and the Gregory Jackson Center, a community “hub” named for a former professional basketball player who returned to the neighborhood to open a recreation center.

They also hope to pique the New York City Department of Education’s interest in using its child care and preschool facilities beyond the traditional weekday hours and allowing family co-ops to operate in the spaces.

“This is a real opportunity for the Department of Education to see how the facilities they run can be used on the weekends. We would like to see this turn into an early-childhood ‘Beacon,’” Belay said, referring to a network of community schools in New York City, San Francisco, Minneapolis and Denver that provide programs for youth and families.

With K-12 educators also involved in the planning process, Belay and Harrington hope to add programs for school-age students in the future.

'Learning to tell stories'

Discover Together Grundy began when Mayes was “exchanging ideas” with colleagues at Scholastic about developing a place-based curriculum. Meanwhile, Emily Partin — the director of the Grundy County School Family Resource Center — was interested in doing two-generational work with families.

The curriculum is different than a typical literacy program in that children learn about themselves, their families and their community. Lessons in the series include themes such as “I can look and learn,” and “I can talk and listen.” In the after-school program, students learn photography and use the photos as part of their stories.

“What we’re talking about is redefining literacy — not just learning to read, but learning to tell stories,” Mayes said. “Learning is not just telling stories in isolation. We tell stories to others. Stories are about relationship. It’s a critical social skill.”

The Grundy families have built connections beyond the co-op sessions and other activities. They created a Facebook page and carpool to field trips. “They think of themselves as a cohesive, supportive group,” Mayes said.

While Mayes has not tracked the children into school to study their later academic performance, she hears anecdotal reports about how they show more curiosity in the classroom. She hopes the spread to Brownsville will provide opportunities for a more formal evaluation. Eventually, the goal would be to publish Discover Together as a curriculum that any community could adapt to its unique setting.

“Every place, whether it’s urban or rural, has things about their community that they want to celebrate,” Mayes said. “Every place can use their community and the things they are proud of as a way to help their children learn these storytelling skills.”