As President Joe Biden announced the end of the longest war in U.S. history, schools across the nation prepared for an influx of refugees, who were among the more than 120,000 people that were evacuated from Afghanistan.

"So many of our students bring their cultural perspective, and they really add diversity to the classroom," said Salimah Shamsuddin, refugee family support coordinator for Austin Independent School District in Texas. The district has been receiving refugees for over 14 years, and has so far enrolled 11 Afghan students from the 100-200 expected families estimated by Refugee Services of Texas. "We're not really sure how many of those families are just couples, and how many are families with kids."

In absence of this knowledge, districts are still partnering with community organizations to offer arriving students and families a host of services, including language support, academic assessments and culturally responsive instruction, drives and donations from families, and housing and healthcare.

'They've seen a lot'

"What's happened just in the past couple of weeks, they've seen a lot," Shamsuddin said. "And so how do we respond to that in the classroom?"

Community and in-house mental health providers are part of the answer.

A smooth registration process "means not only getting them the classes, but also getting them the social-emotional supports that they need to get settled," said Meredith Hedrick, chair of the English for Speakers of Other Languages Department at Annandale High School in Virginia's Fairfax County Public Schools.

The district expects students who have been evacuated from Afghanistan to arrive in the surrounding county, and school staff are helping to expedite enrollment, a district spokesperson said in an email. "It could be therapy or social services. It can be anything as simple as a backpack or other things they need at home, like school supplies," Hedrick added.

In Austin's International High School, where all of the teachers are certified in ESL, and which serves a handful of Afghan students already, a social worker closely working with students was able to apply for and secure housing through the city's rental assistance program. "So just working with families in that capacity, not just in the classroom, but also helping with other needs," Shamsuddin said.

'They need to feel welcomed'

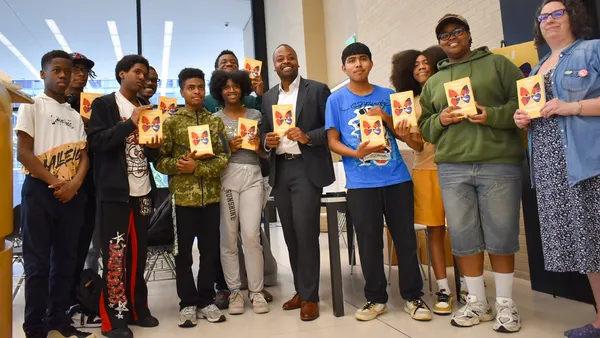

In addition to wraparound services like housing and health care, districts are also preparing to provide academic support. "One thing we do with our refugee families is recognize their strengths and all the efforts that they bring. Often, the work with refugee students is framed as 'needs and deficits and challenges,'" said David Kauffman, executive director of multilingual education at AISD.

In reality, Afghan students and families may speak multiple languages and already be ahead of the academic curve, but just need to feel accepted in order to excel.

"I think especially in this situation, just really knowing who these students are and learning more about their background is really important for them to move forward academically," said Sarah Eqab, assistant principal at Annandale High School. "In order for them to learn, they need to feel welcomed and need to feel like they belong."

Sometimes that requires training teachers to be culturally responsive. "I think we're going to be really in tune to the needs of the Afghan community, and so I think that's going to be an adjustment that we're going to want to learn about — what's culturally appropriate given the circumstances the Afghan community has been through," said Hedrick.

In Austin, the district is training teachers, mental health professionals and counselors. "If you have a father that you're speaking to, there might be some cultural consideration like hand-shaking," said Shamsuddin. "A lot of our dads put their hand over their chests as a 'hello,' and [we have to let] teachers know that that's normal and they do that."

Trainings also emphasize differentiating between Afghan families and those from the Middle East.

In another effort to make environments inclusive for Afghan families, schools are setting up peer or mentor systems with students who speak Pashto or Dari. "Not only do they have adults, but they immediately have another student in the building that can help them," Eqab said.

Technology could be a challenge

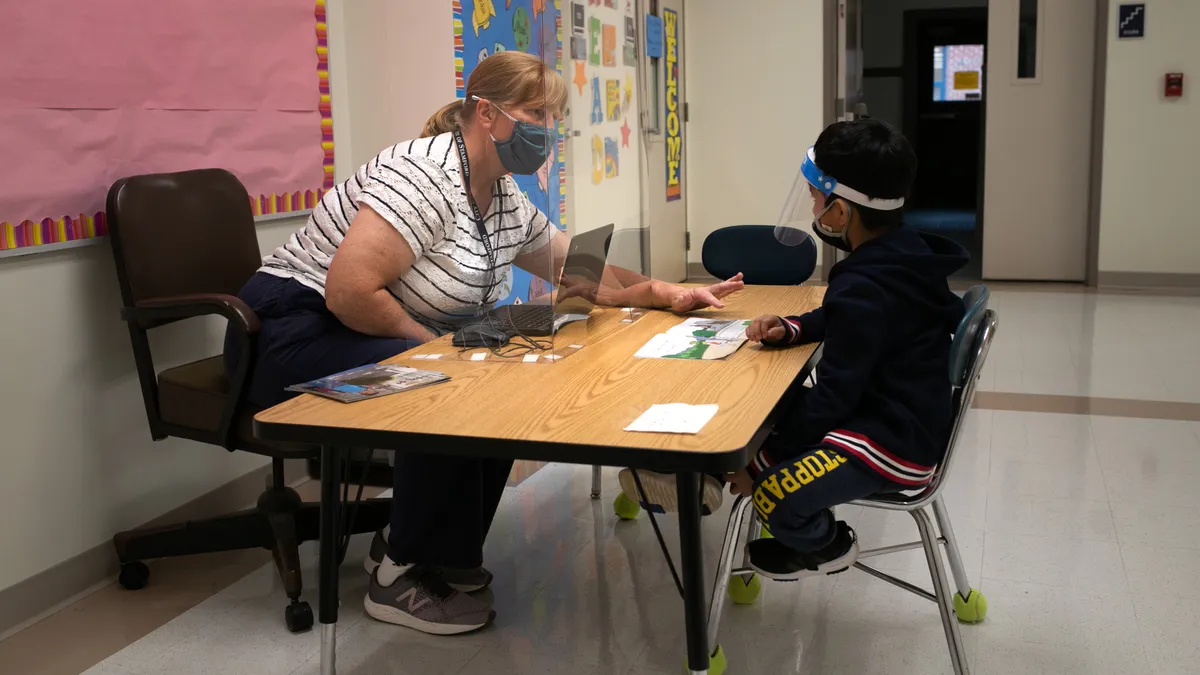

Although some districts have been welcoming refugees for years, this year's enrollment and acclimation could be challenging amid the ongoing pandemic and periodic school shutdowns.

"In the past, if a kid needed to go into vision testing, they would take them to the eye doctor, and it was an easy process," said Eqab. "But because of the pandemic, a lot of things have shifted where parents have to access technology, and they need that support sometimes if they're not familiar with it."

And once families are familiar with district technology, newly enrolled students will have to get the hang of the different programs and platforms schools use, added Hedrick.

"It's just an additional layer for us to help them work through," Eqab said.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards