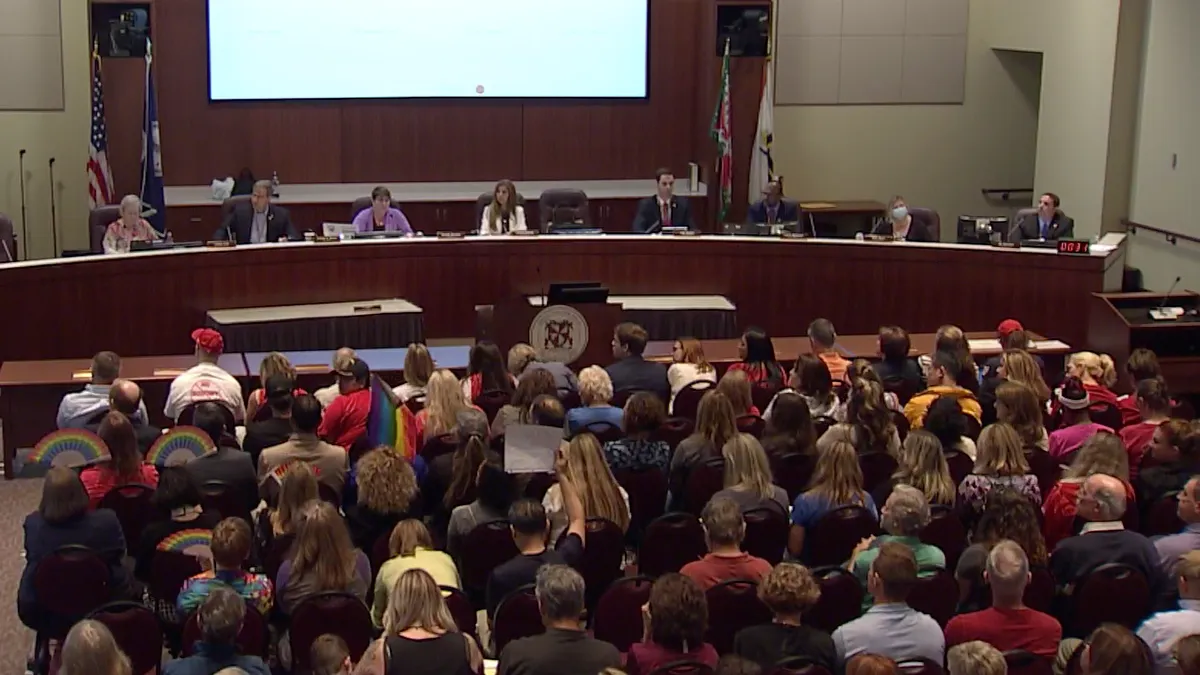

The first 20 minutes of the June 22 Loudoun County School Board meeting in Virginia covered the important, yet mundane business dealings of the growing school system located less than an hour away from the nation’s capital — approvals of minutes of a past meeting, a grant application for the preschool Head Start program, and a contract to renew ice cream offerings in school cafeterias.

During staff and student recognitions, board members and the large audience that had gathered all gave a standing ovation to a school district employee who rescued two people involved in a vehicle accident.

Next on the agenda was the public comment section, and with 259 people signed up to speak, it would be a long evening. But after only one hour, one meeting recess and the testimony of just several dozen people who spoke mostly about the rights of transgender students and critical race theory, the board stopped public comment after audience members began clapping and shouting.

After trying to move on to other business, the board was again interrupted by shouting. The school board broke for a recess and eventually a closed session. One person was charged with disorderly conduct after the public comment session was cut short, according to news reports.

Debate, discourse and conversations about controversial topics are all normal aspects of school board meetings, school attorneys say. While many of the recent intense interactions at board meetings across the country are stemming from polarizing opinions over critical race theory, transgender rights and mask mandates, conflicts over various topics such as dress codes, school boundary changes and budgets have long been part of school board sessions.

What’s concerning now, attorneys say, are efforts to disrupt school board proceedings like what happened in Loudoun, and threatening and insulting behavior witnessed at a few other in-person meetings in recent months and on social media, according to media reports.

Even where there are no incidences of bullying or intimidation at board meetings, school boards are hearing more passionate public testimony at meetings lately, school attorneys said.

Some of the theories for why intense participation is on the rise include recent controversial and political issues, as well as new awareness of local education decision-making as a result of access to virtual board meetings during the pandemic, some legal experts say.

“There have been significant increases in the number of people who want to speak at board meetings and the tone that is tending to take, where maybe some of that polite civics-minded discourse is being replaced with a lot more heated discourse right now,” said Brandon Wright, a school attorney with Miller, Tracy, Braun, Funk & Miller in Illinois, whose law firm posted a recent blog on managing an open meeting effectively.

Bobby Truhe, a school attorney who has been practicing for 10 years and is now with KSB School Law, which mainly represents school systems in Nebraska and South Dakota, also has noted an increase in public participation at board meetings.

“We've had a lot of schools that have been asking questions about, ‘OK, exactly how do we structure a public comment period? What are the reasonable rules that we can have? What decorum expectations can we have?’ Way more so in the last 18 months than probably at any other point that I've been doing this,” Truhe said.

The public’s right to speak

The recent rise of heated school board meetings should not deter school boards from conducting open meetings that include public comment periods in accordance with state and local public meeting policies, said Francisco Negrón Jr., chief legal officer for the National School Boards Association, a federation of state associations of school boards representing 90,000 school board members across the country.

“Intense discourse is, in fact, a basic tenet of our democratic system, and school board members often disagree themselves on positions that the school district is going to take. And of course, it’s subject to majority votes,” Negrón said.

In fact, school systems’ open meeting policies typically favor public participation and the public’s First Amendment right to free speech, Truhe said.

That means a school board’s public comment period typically allows a speaker to discuss any topic, even if it is not related to the meeting’s agenda. It’s the time in the meeting some school attorneys refer to as “karaoke time,” because unlike the rest of the scripted meeting agenda, no one knows what to expect from the speakers.

School board meetings — which in general have low attendance, according to Truhe and Wright — are often held in the evenings and have open comment sessions in the earlier part of the agenda so more of the public can participate, Wright said. School boards can also have public comment periods dedicated to a certain proposal or topic.

When public comments become heated, school board members should avoid engaging in a debate with the speaker, Truhe recommends. If they do start arguing with a speaker, the board member could be violating public meeting laws that restrict members from discussing topics not on the advertised meeting agenda.

“For school boards, generally, they rely on the advice of their attorney members of the Council of School Attorneys, making sure that it's not about curtailing disagreement or unpopular opinions, because those are important and those are valuable to hear, but rather making sure that the process can occur in a way that the comments can be heard and that the school board can continue to do its business,” Negrón said.

Guardrails for decorum

There are also proactive steps boards can take to set expectations for decorum during public comment periods and for open meetings. Some actions include time limits for public comments with a visual clock that counts down a participant's remaining time to speak.

Depending on state and local policies, boards can also have deadlines for speaker signups and can reconvene in larger spaces if the crowd is bigger than anticipated. Boards can also vote to go into recess if emotions escalate or the audience becomes too unruly. A board may also revoke speaker privileges if a speaker violates decorum by using vulgarity or profanity; reveals personality identifiable student information; or breaks other public comment rules set out in policy.

Stating these expectations before the public comment period and consistently following the protocols can set the stage for respectful listening and speaking. Indeed, the audience at the Loudoun County School Board meeting on June 22, at the request of the board chairperson and before the public comment period was abruptly ended, mainly refrained from clapping or shouting and instead silently stood, held up signs or shook their hands in the air when they agreed with a speaker.

School board members should also model professional behavior, Wright said.

Negrón said open public comment periods during meetings are just one way stakeholders can communicate with board members. The public can also request individual meetings with representatives, make phone calls and send emails. But neither those alternative methods of communication nor the enforcement of meeting decorum policies should be construed as restricting the public’s free speech rights, he said.

“I should stress again that that has nothing to do with regulating the content of the speech or trying to stymie intense discourse, which I think is what school boards would welcome," Negrón said. "They want to hear the opinions of the public, particularly the stakeholders in their communities. That's what they're there to do.”