Decaying school buildings, budget strains and enrollment shifts are prompting some district leaders to make the difficult decision to close schools.

These closures can be tough for their communities to process — especially when a school holds historical or cultural significance.

In late June, for instance, New Jersey’s Jackson School District closed its 32-year-old Christa McAuliffe Middle School. The school had been named after the New Hampshire high school teacher who died in the 1986 tragic explosion of the Challenger space shuttle shortly after launch — while a nation of horrified students and educators watched on live television.

The district held a ceremony in June to honor and remember the school’s history. Christa McAuliffe Middle School closed as Jackson School District faced a steep post-pandemic enrollment decline and significant budget challenges.

The district’s school board also filed a lawsuit in February against the New Jersey Department of Education alleging that an inequitable funding formula forced the school closing to help address an “ever-widening budget gap,” said Tina Kas, the district’s board president, in a Feb. 19 statement.

Community engagement is key

Holding an event to help a community say goodbye to a closing school is “a wonderful way” to approach this kind of difficult move for districts, said Barbara Hunter, executive director of the National School Public Relations Association. “Because it can be a grieving process, really, for some families.”

At the same time, Hunter said, districts need to think about how to welcome families and help them get acclimated to their new school after a closure.

When it comes to school closures, it’s key that district leaders start community conversations early — often several years before the building must shutter, Hunter said. Doing so allows a district to ensure that stakeholders understand the process and address their concerns.

“A district can take a real reputation hit in terms of trust and confidence if they don’t fully engage all those impacted by the proposed closure,” Hunter said. “So I know it’s hard to deal with angry parents, but it’s really imperative that districts engage those folks.”

When closures are tied to declining enrollment and budget strains, Hunter said, school leaders should explain how their situation is part of a broader trend nationwide brought on at least partly by declining birthrates. Understanding the context “can help ease pain a bit,” Hunter said.

Still, districts need to be careful that school closures don’t come off as just a “cost analysis situation,” Hunter said, especially when the closure impacts a school that is the heart of a neighborhood or community.

Districts need to communicate face-to-face as much as possible in addition to posting on social media and the district’s website, she said. The key focus should be how the change will benefit students and families, and it’s up to teachers, principals and even PTA members — rather than just the district central office — to understand and communicate that message to the community.

While comprehensive national data on school closures is lacking, a January study by the Reason Foundation showed public school closures on the upswing again in 15 states in the 2023-24 school year. School closures in those states had climbed to 98 in 2023-24, up from 65 in 2021-22. In 2019-20, the 15 states had experienced 99 closures.

Preserving a school’s legacy

When the school board for Horry County Schools in South Carolina decided to construct a new building for Whittemore Park Middle School several years ago, some in the community weren't happy, said district staff attorney Kenneth Generette, who also oversees communications for the school system.

The point of contention, he said, is that the middle school would now be on a new site — and no longer on the land where a historically significant segregation-era school for Black students once stood.

The former middle school, built in the early 1990s, included some construction from the original Whittemore High, said Ben Fowler, a writer and editor for Horry County Schools’ communications department. Whittemore High opened in 1954 and closed once the district officially desegregated in 1970, according to the Horry County Historical Society.

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down state-sanctioned racial segregation of public schools, South Carolina kept its school systems completely segregated until 1963. Some schools still did not comply with desegregation orders until 1970, when the federal government began to withhold funds from segregated districts.

As the Horry County district began to plan for its new middle school, a group of Whittemore High alumni pressed school leaders on how they would preserve the former school's legacy, Generette said. During those conversations, the idea emerged to create a legacy room in the new building to display archives and video interviews documenting the high school's history and alumni experiences.

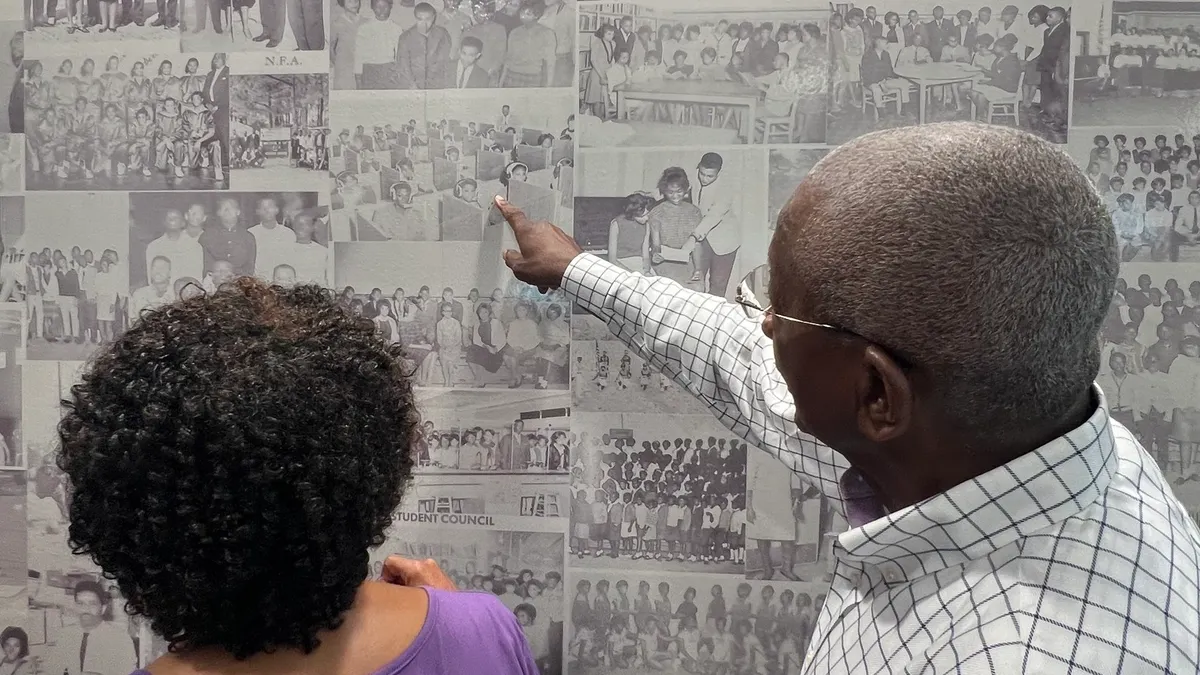

The new school opened in July 2024, with the legacy room just across from the main office. It features a 28-foot-wide wall completely covered in black-and-white yearbook photos from Whittemore High, along with tablets for visitors to peruse digital copies of every yearbook from Whittemore High, and a video loop of alumni interview clips running on a monitor screen. In addition, the legacy room doubles as a conference room for the school.

“These community members were kind of feeling unseen, unheard,” Fowler said. “Whittemore represented a time in history that is uncomfortable to think about, and so a lot of times, people tend to put that out of sight, out of mind. And this project helps them feel seen and heard again, helps them feel like they mattered.”

The new school, which is less than two miles from its predecessor, was built to replace an aging facility and address enrollment growth, Generette said. Horry County Schools has since made some upgrades to the original building and repurposed it for adult education classes and other programs, he added.

Building trust amid a closure

Becky DeWitt, who was working part-time with the district’s facilities department, played a key role in facilitating the district interviews with alumni who she knew through personal connections within the community. DeWitt had attended one of Horry County’s all-Black schools just before integration, “so she knew a lot of these people,” said Ashley Gasperson, the district’s digital communications coordinator.

“Becky was critical, and having someone like that in any community that you can partner with to help build that trust is, I think, very important,” Gasperson said.

DeWitt said it was important for her to listen to and then amplify the alumni voices, especially since some of the former students died after she and the district interviewed them.

Other districts looking to do similar work shouldn’t hesitate, DeWitt said, “because some of the voices you may need to hear from could be lost because of time.”