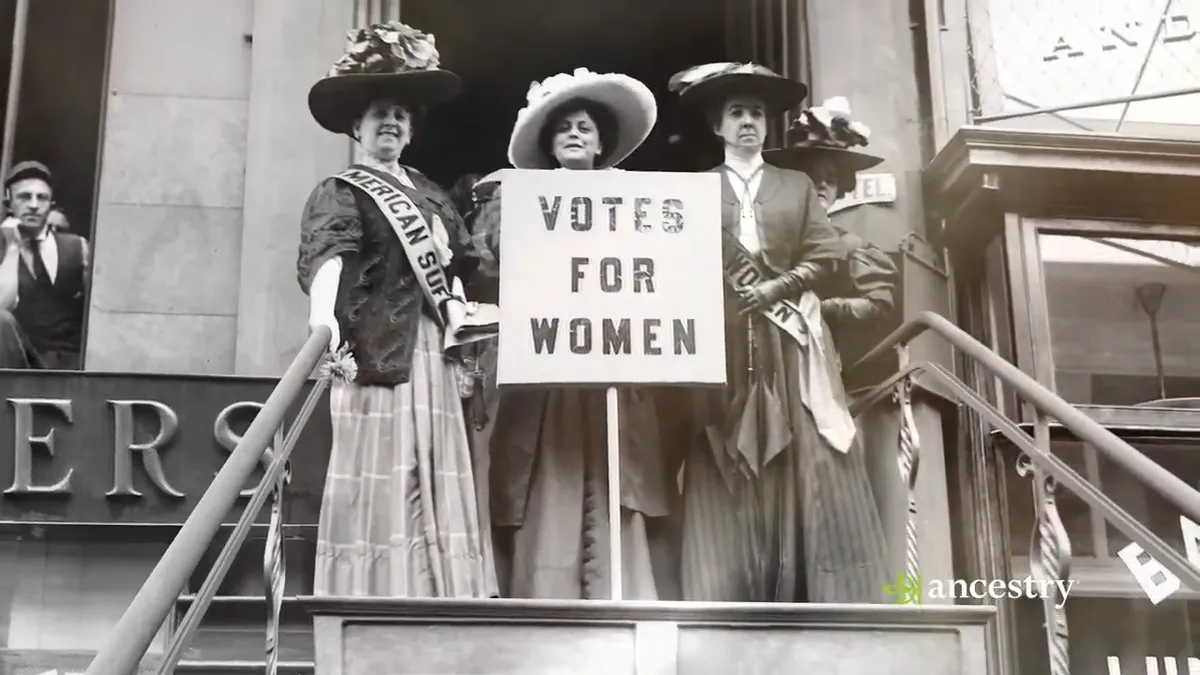

While much is made of the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment this year, historian Johanna Neuman notes that women have been fighting for the right to vote more than a century earlier. The scholar in residents at American University nods, as one example, to Abigail Adams and the sharp suggestion she wrote to her husband “to remember the ladies" in 1776, when he set off to the Continental Congress.

“She warned in her famous letters that if they are not included, they will foment a rebellion,” Neuman said to Education Dive.

That rebellion may have taken some time, but the role of women in landmark events across the United States, from civil rights to sports, has been present throughout the nation’s history. Alongside men, women broke new ground, not just for the country but also for each other, acting as pioneers for the women who followed.

Historians are eager for these women to be better known, eager to breathe new life — and new points of view — into history that many students, and their teachers, may not know today.

Founders of citizenship schools

The civil rights era is studded with extraordinary women, notes Neuman, including African American organizers who were instrumental in securing voting rights for their community. One includes Septima Clark, a civil rights activist whose father, a former slave, had “inculcated in her the importance of an education,” said Neuman.

Clark would go on to open Citizenship Schools, places where men and women could meet and learn the tools they need to get jobs and pass literacy tests. Martin Luther King Jr., after hearing about her programs, encouraged their spread across the South, crediting Clark with launching them, said Neuman.

Neuman also points to Vera Mae Pigee, who opened a beauty salon in Clarksdale, Mississippi, launching her own Citizenship School in the back, and was, “…personally responsible for registering 100 African Americans to vote,” said Neuman.

Fannie Lou Hamer was another woman who built on the struggle of the suffragists who came decades before her. The civil rights activist also wanted women to enjoy even more representation in the political arena beyond simply voting.

As the vice-chair of the Freedom Democratic Party, and a civil rights activist, Hamer spoke on these points before the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Hamer pushed for more women to be part of the decision-making process in the Democratic Party, said author and historian Kate Clifford Larson, who is writing her upcoming fourth biography on the activist, "Walk With Me: a Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer."

Recognition in public spaces

Larson believes Hamer is not just an important figure in the history told about women’s rights, but also as a pioneer young girls today can look to as a role model when they imagine forging their own paths for the future.

“I think it’s hard for girls and women to imagine themselves in these places if they don’t know about the women before them who fought for what they believed was right,” Larson said to Education Dive. “To have to recreate the path and model each time, that takes a lot of energy that doesn’t have to be expended if there’s a model for that.”

Finding those role models would be that much easier, notes Larson, if women were honored and celebrated more often in the public sphere. That can include statues, parks named for them or even highways bearing their name.

For example, Harriet Tubman, the focus of Larson’s 2003 book “Bound for the Promised Land,” now has a portion of the Old Dixie Highway and West-Dixie Highway in Florida named for her, after Miami-Dade commissioners approved the name change in February 2020.

“If we see more statues of women and parks named after women, then people will pay attention more,” said Larson. “That’s where people learn history. All this percolates in the public sphere.”

Helping students identify local unsung heroes and push for their recognition in similar public spaces could provide an opportunity for lessons in civic engagement on that front.

Breaking new ground in athletics

If any part of the public sphere universally captures people’s attention, it’s sports. And many female athletes — some better known than others — have helped expand the rights of women through their accomplishments, as well.

Amanda Regan, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, points to Babe Didrikson, the first woman to win two gold medals, which she earned at the 1932 Olympics for track-and-field contests.

She also attracted a great deal of backlash for being a woman who excelled in sports, an activity not considered “feminine,” Regan told Education Dive. Yet her athleticism was renowned, with Dickerson as well known for her skills in basketball, golf and baseball.

"She got her nickname for getting home runs," said Regan. "And that’s how she got to be called 'Babe,' for Babe Ruth."

Wilma Rudolph, another sports figure Regan highlights, was at one time considered the fastest woman in the world and played a crucial role in helping boost the U.S. position on the sports field during the Cold War, said Regan.

Rudolph won several track medals, including three gold medals in the 1960 Olympics in Rome, during a time when the U.S. and the Soviet Union were engaged in competition on every front, noted Regan. As the men failed to bring home significant medals during the summer games, Rudolph shined, helping to bring recognition to the U.S.

As such, she was “very important as she is able to contribute to this effort,” said Regan.

These women and their important contributions, academics note, may sometimes be lost in history textbooks. But there’s been more effort, if not sporadic, in recent years to uncover more hidden figures and restore the pivotal roles women have played on history’s stage.

“It’s been a long, inconsistent effort, with all these dips and downs, to start to recover women in these stories,” said Regan. “It’s been evolving.”