States suing the U.S. Department of Education over its mass layoffs claim the reduction in force is impacting the agency's legally required functions, including research and grant distribution. But in documents submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court on Monday, the Education Department said states "have no statutory right to any particular level of government data or guidance."

The department is pushing the high court to let its massive RIF go through after being paused by both a federal district judge and the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. In court documents, the agency said "it can carry out its statutorily mandated functions with a pared-down staff and that many discretionary functions are better left to the States."

Its request to carry through on the RIFs comes even as the agency notified "all impacted employees" on administrative leave in a June 6 email obtained by K-12 Dive that it is "actively assessing how to reintegrate you back to the office in the most seamless way possible" to comply with the court orders.

On June 16 — the same day as the agency's latest Supreme Court filing — it also emailed RIFed staff for information to help the department in "understanding potential reentry timelines and identifying any accommodations that may be needed."

However, several of the more than 1,300 department employees put on administrative leave in March told K-12 Dive last week that they do not think the agency intends to actually bring them back. This is despite many of the employees having worked on legally required tasks the department has lagged on or trimmed down since the layoffs, as well as the department's efforts to seemingly comply with the court orders.

"While they're saying we're coming back, they're also still appealing the [RIF] process," said one Education Department employee who is on administrative leave because of the RIF. "It feels like they're slow-walking it."

Employees 'in limbo' as department lags on statutory tasks

The department is still paying all these employees' salaries — amounting to millions of dollars — only for them to sit tight.

According to an email from American Federation of Government Employees Local 252, the union representing a majority of the laid-off employees, the Education Department is spending at least $7 million in taxpayer dollars per month to workers on leave.

That amount is, in fact, only for 833 of the 962 laid-off Education Department workers that the union represents and whom it was able to reach for its analysis. Thus, much more than $7 million is actually being spent per month to keep the more than 1,300 laid-off employees on payroll.

Since March, the department has spent approximately $21.5 million on just those 833 employees, according to data provided by AFGE Local 252.

While the Education Department emailed laid-off employees multiple times in the past month to gather information for "reintegration and space planning efforts" on government IDs, retirement plans and devices, among other things, several employees called this a superficial effort to comply with court orders.

In the meantime, employees are free to apply to other jobs, start their own organizations, and go on vacation if they so choose, according to employees K-12 Dive spoke with as well as an AFGE Local 252 spokesperson.

"We feel like we're in limbo," said an employee who has been on administrative leave since March. "They haven't talked to us."

This employee and the others who spoke to K-12 Dive asked to remain anonymous for fear that identification could negatively affect their employment status or severance terms.

Condition of Education report falls behind

This employee would have been working at the National Center for Education Statistics on data related to the Condition of Education Report, which is required by law — and for which the department missed its June 1 deadline "for the first time ever," according to Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash.

After leaving just a handful of employees in NCES, the department has so far released only a webpage titled "Learn About the New Condition of Education 2025: Part I," which includes significantly less information than in previous years.

"Now all we have is a bare-bones ‘highlight’ document with no explanation to Congress or to the public," Murray said in a June 5 Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing. "And that is really unacceptable — students, families, teachers all deserve to see a full report."

In 2024, the report was a 44-page document including new analysis, comparisons with past years, and graphs to visualize the data. It included over 20 indicators grouped by topics from pre-kindergarten through secondary and postsecondary education, labor force outcomes and international comparisons. Individual indicators ranged from school safety issues like active shooter incidents to recovery from the coronavirus pandemic.

This year, the department said it would be "updating indicators on a rolling basis" due to its "emphasis on timeliness" and would determine "which indicators matter the most." More than two weeks after its missed June 1 deadline, however, the report still only includes a highlights page with five indicators linking to data tables, many of which had already been released.

Meanwhile, Democratic lawmakers have also expressed concerns that the department lagged on its statutory responsibilities to disburse key federal funds, including for Title I-A — which they said took three times as long to distribute than under the last administration. The delay in funding distribution gave states and districts less time to plan for helping underserved students, including those experiencing homelessness, lawmakers said.

The U.S. Department of Education did not respond to K-12 Dive's requests for comment on its missed June 1 deadline for the report or on how it will increase government efficiency and cut costs while spending millions on salaries for employees who are not working.

Department says RIF impacts are "speculative"

However, in its Supreme Court filing on Monday, the department dismissed as "speculative allegations" states’ complaints of disruptions to services as a result of the RIFs.

The states, in their filing last week seeking to block the RIFs, said that "collection of accurate and reliable data is necessary for numerous statutory functions within the Department that greatly affect the States."

The department relies on this data "to allocate billions of dollars in educational funds among the States under Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act," the states said in their June 13 response to the administration's plea to the Supreme Court to let its RIFs take effect. The department has given "no explanation of how such allocation can occur without the collection and analysis of underlying data, or of how the data can be collected or analyzed without staff," their filing said.

In its Monday response, the department maintained that it is not required by law to maintain "a particular quality of audit." The states arguing to maintain the department's previous staffing levels are trying to "micromanage government staffing based on speculation that the putative quality of statutorily mandated services will decline," the agency said.

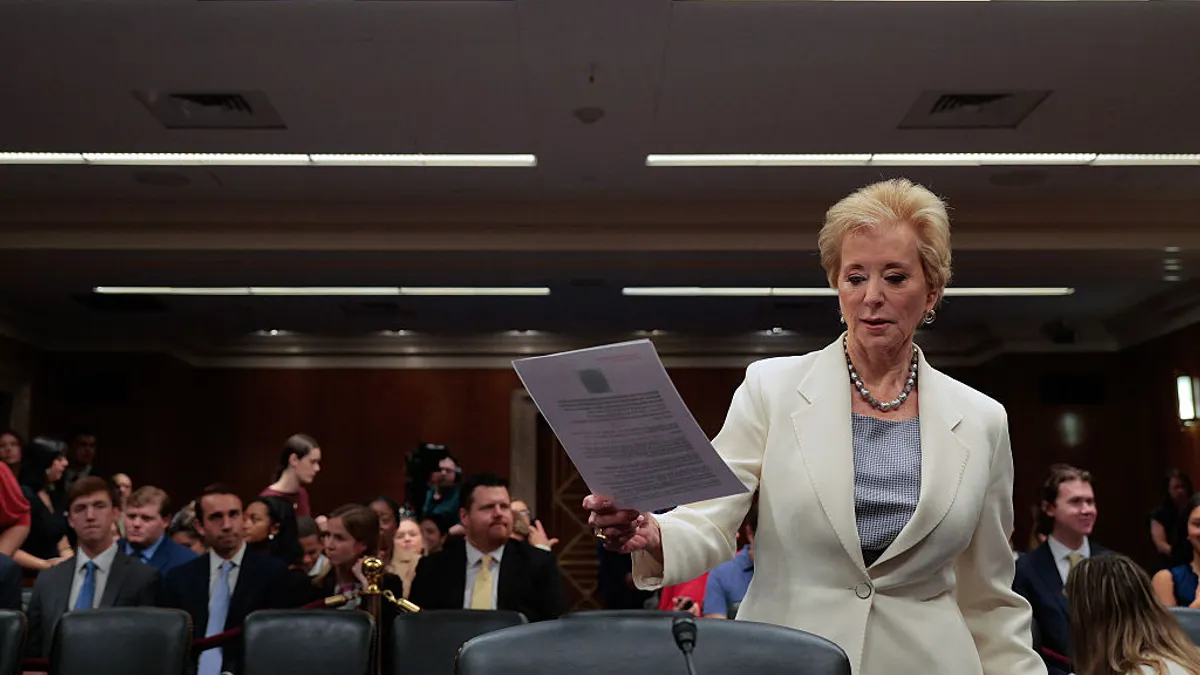

However, when pressed by Sen. Murray in a budget hearing earlier this month, Education Secretary Linda McMahon said "no" analysis was conducted about how the firings would impact the agency’s functions or how it would continue its statutorily required responsibilities without much of its staff. The department did read "training manuals and things of that nature" prior to the layoffs, she said, and had conversations with "the department."

But several laid-off staffers told K-12 Dive that they were never spoken to about how their responsibilities would continue to be fulfilled after their departure.

"They don't understand what they've cut," an employee said.