This week, K-12 Dive is on-site in Austin, Texas, at the SXSW EDU conference. Below is a recap of sessions during the conference's second day.

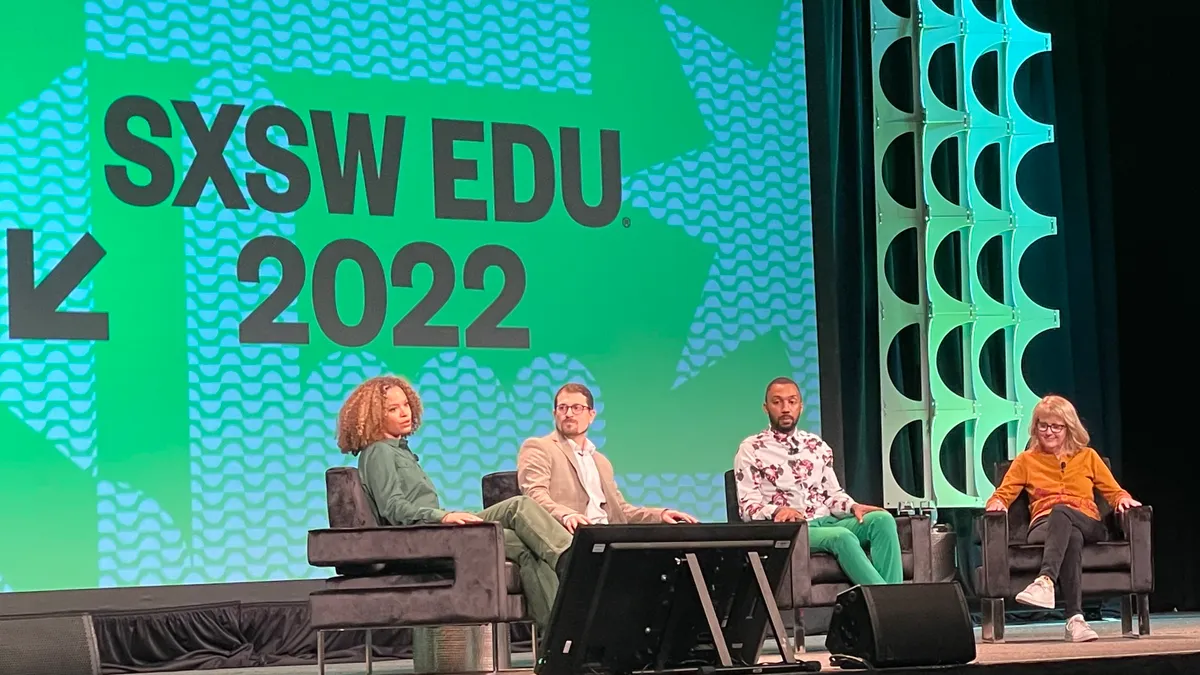

SXSW EDU rolled into Tuesday, opening the day with a keynote panel focused on the culture wars that have slammed into schools in recent years.

The conversation was led by NBC News Correspondent Antonia Hylton and Senior Investigative Reporter Mike Hixenbaugh, hosts of the Southlake podcast, which focuses on how a Houston, Texas, suburb and its school board election became wrapped up in backlash against a Cultural Competence Action Plan designed to improve diversity and equity, as well as the critical race theory debate.

Joining them were Carolyn Foote, a recently retired district librarian in the Austin area, and George M. Johnson, author of the New York Times young adult bestseller “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” which is being banned or challenged in about 20 states.

“Ultimately, it’s about children’s lives and educational opportunities, but they seem to be excluded when parents and politicians are fighting about these issues,” Foote said.

Last spring, Foote was starting to see challenges to book titles related to diversity, equity and inclusion, with more parents raising concerns. Then in October, Texas Rep. Matt Krause, a Republican, released a list of around 850 books he said could make students “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex."

The list was heavily dominated by titles with racial and LGBTQ topics and themes, and written by authors of color and those from the LGBTQ community. It has since spread and been used across the country, Foote said, and is now being “weaponized” against schools and libraries.

Johnson, who is Black and queer and uses they/them pronouns, said they didn’t have any literature they could see themselves reflected in when they were growing up. So they wrote a book for the 5-year-old them who didn’t have words to explain what they felt at that age, the 10-year-old them being called a gay slur for the first time, and the 17-year-old them who couldn’t attend prom with the person they preferred, Johnson said.

The book is now banned in school libraries in at least eight states — including Pennsylvania, Florida, Iowa, Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, Virginia and Texas — and has also been the subject of criminal complaints in Florida and North Carolina, on the grounds it violates obscenity laws over graphic sexual content.

Johnson stressed that libraries and librarians are a critical resource for children and teens. Making an analogy, they said book bans were akin to going to a supermarket and saying that because you don’t like Pepsi, the store can’t sell Pepsi to anyone. Likewise, just because one parent doesn’t want their child to read a certain book doesn’t mean they should be able to remove that choice from other parents.

Foote added that a lot of times, imprecise language is used to trigger people’s reactions and take advantage of a moment, and this is happening now with people calling LGBTQ-related library books “pornography.”

Johnson suggested that because populations and demographics are shifting faster than people thought they would, an internalized fear is welling up in regard to what happens when a majority becomes a minority. “This is really just a fight about stopping the truth,” Johnson said.

“Think about a library like a supermarket. You have the right to choose which Cola you want to drink, but if you don’t like Pepsi, you don’t have the right to tell the store they have to stop selling Pepsi!” Thank you @IamGMJohnson for that comparison. @SXSWEDU #sxswedu pic.twitter.com/79lH2KZ5Rf

— ????Deanna Perkins???? (@PerkinsClass2) March 8, 2022

“One of the hardest things as an educator is to see this become a political effort. There’s a playbook now. Political figures are using this to win elections on the backs of teenagers.” @technolibrary #SXSWEDU

— Liz GE (@LaLaLoveLiz) March 8, 2022

“Parents don’t have the right to ban books I think my child needs…When we ban books, we’re saying ‘that story doesn’t matter’ or ‘that story doesn’t exist.’”@IamGMJohnson preaching this morning at #SXSWEDU pic.twitter.com/mtvggjCDjf

— Ali Goljahmofrad (@aligoljahmofrad) March 8, 2022

Media literacy is more than detecting fake news

In a morning session, Michelle Ciulla Lipkin, executive director of the nonprofit National Association of Media Literacy Education, explained the value of teaching students how to spot and tackle misinformation — and why there’s more to media literacy than that alone.

It’s key that media literacy be seen not as a class to teach but rather a skill set that can be applied in any subject, Ciulla Lipkin said.

“For us, media literacy is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create and act using all forms of communication,” Ciulla Lipkin said.

The growing conversation surrounding "fake news" has put media literacy into the spotlight, she said.

But while identifying fake news is a great starting point, she said, once misinformation is spotted, it’s equally critical to know what to do about it and how to understand that information.

“One of the struggles with things like disinformation, misinformation and fake news is that it tries to put information into, kind of, two buckets,” Ciulla Lipkin said. “It tries to identify if it’s true or false or fact versus fiction.”

But information is a lot more complicated than that, Ciulla Lipkin said, and there’s still a lot more information that needs to be understood, including that there are disinformation campaigns working to spread fake news.

Most information can’t only be labeled as fact or fiction, either, she said, adding it’s actually, “somewhere in between.”

“It’s that gray area, and how do we get kids to understand that gray area?” Ciulla Lipkin asked.

‘Learn-and-earn’ expands pathways to skilled jobs

In a Tuesday morning session, workforce pathway experts debated the best way “learn and earn” programs can serve the growing need for skilled workers in STEM and other fields. These programs include apprenticeships, internships, co-op models, practicums and work studies — and while they're often associated with higher ed, there are also applications for K-12 career and technical education.

For instance, Lydia Logan, vice president of global education and workforce development at IBM, works with programs like STEM for Girls, which focuses on closing gender gaps in related fields, and Pathways in Technology Early College High Schools (P-TECH), a program working to expand opportunities to students from underserved backgrounds.

“Our belief is that people are not taking one path from high school to college to work,” Logan said.

One way IBM has acknowledged this is removing four-year degree requirements from about 20% of jobs, she said, resulting in a 63% increase in underrepresented applicants.

Lumina Foundation President and CEO Jamie Merisotis said more focus should be given to the idea that all learning — from prior job experience and credentials to degrees — should count when preparing people for work and life. In addition, he said, soft skills should be viewed more as “durable skills” because they are crucial in the work world.

Still, he said, better systems for measuring skills like critical thinking, problem solving and communicating must be developed.

While the four-year degree is unlikely to go away, the panelists said, going to college and getting a bachelor’s degree is no longer the most viable option for most of the workforce. As such, education and industry must ensure capacities to provide access to alternative pathways are continuously upscaled to meet those demands.

What’s needed to disrupt racial inequity in schools?

In an afternoon conversational session, Tequilla Brownie, CEO of The New Teacher Project, a nonprofit focused on ensuring all students have high-quality teachers, detailed factors needed to disrupt racial inequity in K-12 schools.

Brownie, who grew up in poverty in Arkansas before going on to attend Yale University, said her lived experiences were the exception and not the rule in a system where the racial wealth gap is growing and pervasive — particularly for Black and brown students.

Nonetheless, those experiences, as well as her professional background in social work and education, give her a clear sense of what’s needed to help education become the “great equalizer” it’s meant to be, she told Kevin Michael Foster, chair of African and African Diaspora Studies at University of Texas at Austin and an Austin Independent School District board trustee.

Over the course of the hour-long discussion, Brownie expounded upon the importance of diverse teacher forces, the roles policy and lawmakers’ ideologies play in improving K-12 equity, and more.

Stay tuned in the coming days for a full recap of the session.

3 takeaways from one Georgia district’s success in future-proofing the classroom

Georgia’s Henry County Schools serves more than 42,000 students across 50 schools. Months before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the district set up a connected learning system with high-quality curriculum, which it calls a “future-proofing” strategy.

Future-proofing is defined as a system to ensure all students can still learn even if there’s an ongoing crisis, as happened with COVID-19, said Benita Flucker, senior vice president of enterprise development strategy & services at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. HMH is an ed tech provider partnering with Henry County Schools on this effort.

Below are three takeaways from Henry County Schools’ shift to a future-proof model, shared by district leaders during a session Tuesday afternoon:

-

Henry County Schools has not seen the same “dire gaps” of learning from the pandemic that other districts are noticing nationwide, said Melissa Morse, the district’s chief of learning and performance.

-

A key part of future-proofing is being strategic about technology partnerships with vendors, said Superintendent Mary Elizabeth Davis. Before Davis joined the district, Henry County Schools spent too much money on resources that weren’t addressing its learning needs, she said.

-

This kind of innovative work can’t be done if there’s no foundation or clear direction for students, Davis said. A community must help drive these efforts, and a teacher or superintendent cannot lead these efforts on their own, she said.