Few education researchers have had as much influence on educational policy and practice over the past quarter century than Linda Darling-Hammond. A former teacher and school founder, the Stanford University scholar is president and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute, and last year, she was appointed president of the California State Board of Education.

In this Q&A, Darling-Hammond discusses the state board’s response to the COVID-19 crisis, how school closures are affecting her research interests and the lessons she hopes school leaders take away from her work.

Editor's Note: The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

EDUCATION DIVE: After a year as president of the state board, how has your approach to issues facing the state in the role of a policymaker been different from that of being a researcher?

LINDA DARLING-HAMMOND: I’ve always been involved in research and policy, and they are two different ways of thinking. When you’re doing research, you’re looking for answers to questions that assume best circumstances. Under the best circumstances, what would you do to get a certain kind of an outcome? In policy, you have constraints, you have prior conditions, you have things you need to build on and obstacles you need to get past.

You bring a lot of additional variables into play when you’re thinking about policy. I do try to contribute and think about the research implications for what we’re doing, but then you’ve got to think about what’s doable in the context you’re in.

What has been the role of the state board in this current crisis?

DARLING-HAMMOND: The executive order Gov. Gavin Newsom issued promised to maintain [average daily attendance funding] for schools with the expectation that they would offer distance learning, provide meals for kids, and, to the extent practicable, support child care for first responders and essential workers. Then, we needed to figure out how to support districts to do those things. In some states they closed schools and did nothing.

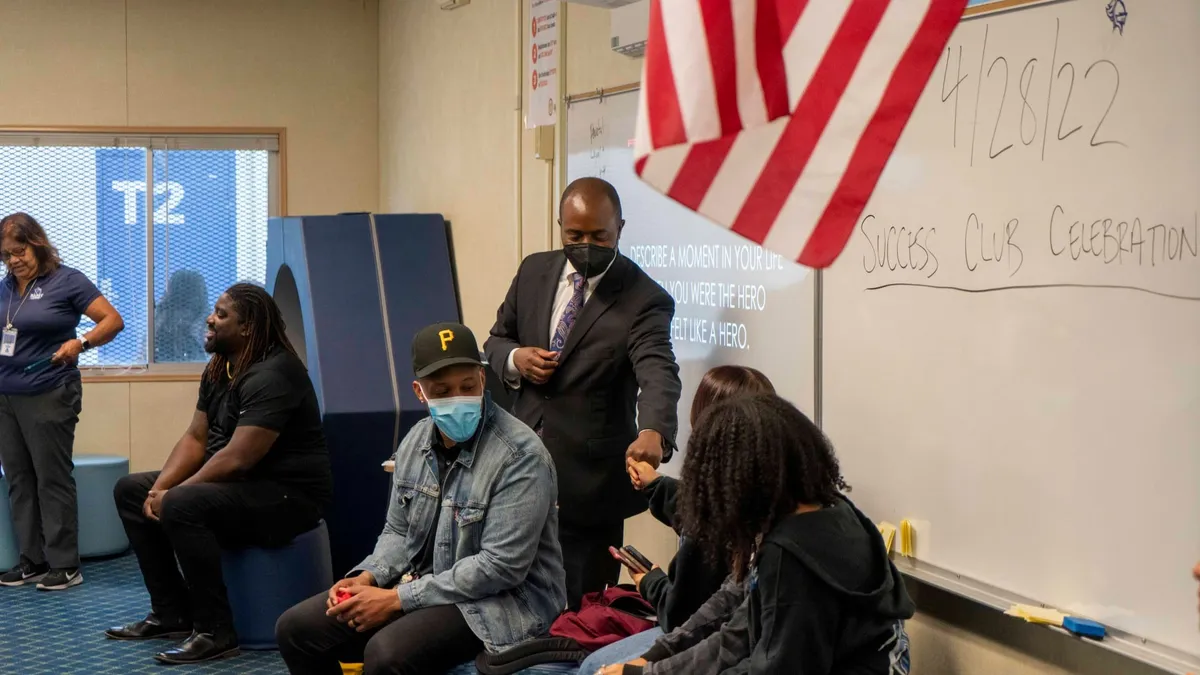

With the [state] Department of Education, we’ve been providing guidance on distance learning resources. Right now, we’re busy collecting contributions from a variety of corporations and foundations and companies who want to contribute devices and Wi-Fi and bandwidth and meals. We're helping to coordinate all of that, giving [schools] guidance on how to do distance learning — both with packets and with digital resources — [and] providing curriculum if they don’t have it. We’re trying to link people together so districts that are further ahead can be instructors to those figuring it out.

We’re also putting out guidance on grading and graduation requirements, working with the higher ed community to see what flexibilities can be arranged for kids trying to gain admission to colleges and universities. Many things have to be rethought and redone. We have to think about how we are going to maintain our accountability system in California, so we’re also developing guidance on that.

In all of these things, we try to touch base with people in the field and understand what their experience is and work with the governor’s office, the department and the legislature to figure out what we need to do to get it done.

Has being on the board influenced what you want to focus on as a researcher? What are you working on now?

DARLING-HAMMOND: I’m kind of an omnivore when it comes to educational research. I’ve always wanted to figure out what it would take to provide good education to all kids. It’s taken me in my career to studying school finance, teaching quality, school design and organization, and a variety of other things that help us get to that answer.

Right now, I’m learning a lot about distance learning and how it can be done well, so that’s become a new interest. We’re finding out how to do social and emotional learning through distance learning as well as content learning, which is really important at a time of heightened trauma and adverse conditions for kids.

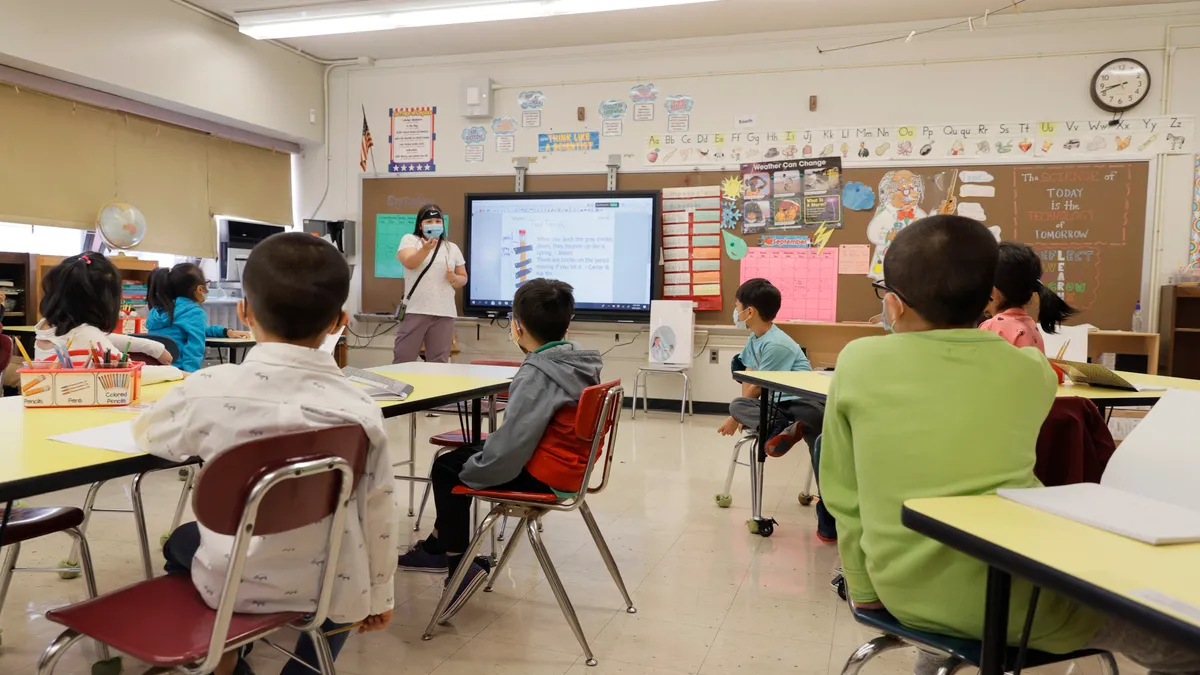

We also have these opportunities in the time of COVID-19. We have about one in five kids in California who have not been digitally connected at home, either because of Wi-Fi or device limitations they have. We’re actually tackling this in a very assertive way right now with the idea that we might be able to close that digital divide by next year.

We’ll use the impulse of the folks that want to help, and they say necessity is the mother of invention, to start next school year — whenever it starts — with everybody able to engage in the digital learning process. That means we may not only be able to handle school closures, which God knows with all the natural disasters can come on many occasions, but we can also begin to infuse technology into learning and get kids to be more independent learners in using technology in ways that weren’t happening before because we didn’t have to figure it out.

What do you most hope school leaders — and emerging researchers — take away from your work?

DARLING-HAMMOND: My own experience is that you have to think about everything in systems terms. Quite often in education, people have the one silver bullet, or they look for the one silver bullet. If we just buy this curriculum or if we just adopt this program, everything will be all better. I’ve been a teacher and worked with a lot of educators and started some schools, so I see it on the ground as well as in my research.

You learn everything is connected. So, if you pull on one string in a tapestry, you get a tangle. What you really need to do is think about the whole piece and how you’re going to move all the parts in a direction of greater opportunity.

For example, in California, we’ve [achieved] a much more equitable resource system in recent years as a function of my predecessor on the state board, Mike Kirst, and Gov. Jerry Brown. We still have to work toward greater adequacy under that funding system. But then we have to be sure we have well-prepared educators who know what to do with those resources in terms of meeting the specific learning needs of kids.

And there’s a gigantic knowledge base for teaching and school leadership, grounded in what we know about how people learn, how they are motivated, how they learn content, and what the social-emotional implications are for their self-identity and their ability to function.

You have to worry about whether the nature of the learning and the assessments point toward the kind of learning we need today in the 21st century, not just memorizing information but using it in productive approaches to problem solving. You need to think about whether there are supports for children in their homes and communities, particularly at a time when we have so much poverty, food insecurity, health care insecurity.

We’re thinking about how you build community schools that provide those integrated supports. If our system works, it will attend to all of those things, and if our schools work well, they will also attend to all of those needs children have.

Much of your work has focused on teacher shortages. How do you think the current school closures and the economic impact of the pandemic will affect staffing?

DARLING-HAMMOND: We’re clearly going to go into an economic downturn. Some people say it will be akin to the depression of the 1930s. Some folks also say it may give us an opportunity to recreate a more equitable New Deal as we did in the ‘30s, because the needs of people are so great.

Whether it’s a recession or a depression, we’ll see. But it also will bring the central importance of public education back to people’s minds. People are relying on schools to feed children, to be the outreach point for a lot of social services that are needed, to provide education to try to ensure we don’t get a growing equity gap.

In terms of teacher shortages, what often happens when you have less money is you hire fewer teachers. That’s what happened in the last recession. Class sizes in California went up to 40 or above. Unfortunately, that could happen again. When you’re pink-slipping teachers, you’re worried less about shortages. Teaching will look like, hopefully, secure work. Many people who might have been holding out for a job in the tech community maybe will say teaching looks like secure work at this moment in time when employment is so unsteady.

If we’re smart about it, if we have fewer shortages, we’ll use that time to improve the quality of preparation they get. Right now, half the people coming into teaching in California are not fully prepared to teach. But if is there is less demand, we should give them a really high-quality preparation so they are able to be effective with kids.

We also know that keeps more people in the profession. If they are better prepared, they are much less likely to leave. So, we should use that as an opportunity to build the strength of the pipeline and the preparation system so that when we get an expansion of opportunity to hire people, their experience coming into the profession is much better.

What are some lessons you’ve taken away from your study of education systems in other top-performing countries?

DARLING-HAMMOND: One of the interesting things about studying other countries is [with] much of what they do, they will credit the U.S. with having taught them to do it, but then they scale it up so everybody gets it. One of the things that we’re so bad at in this country is scaling things up. We had some really productive work going on by states in the 1990s, and then that really got pushed back — both by budget cuts and by a narrower view of the work.

We have inequitable funding in most states such that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. There are a few states that stand in contrast to that. Then foundations will fund things. Maybe there’s a pilot project that lasts for a certain number of years, and then there’s no government money coming in to pick it up and it goes away. We innovate in what I think of as a popcorn fashion. We’ve got innovations all over the place, but they don’t get scaled up and embedded in systems so everybody can get access to them.

We have invented just about everything, and other countries will say, “I learned to do this when I came to the U.S. and looked at this innovation,” but we don’t stay the course.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards