When all is said and done, 2020 could go down as arguably the most disruptive and transformative year for K-12 curricular approaches in the history of the U.S. public education system.

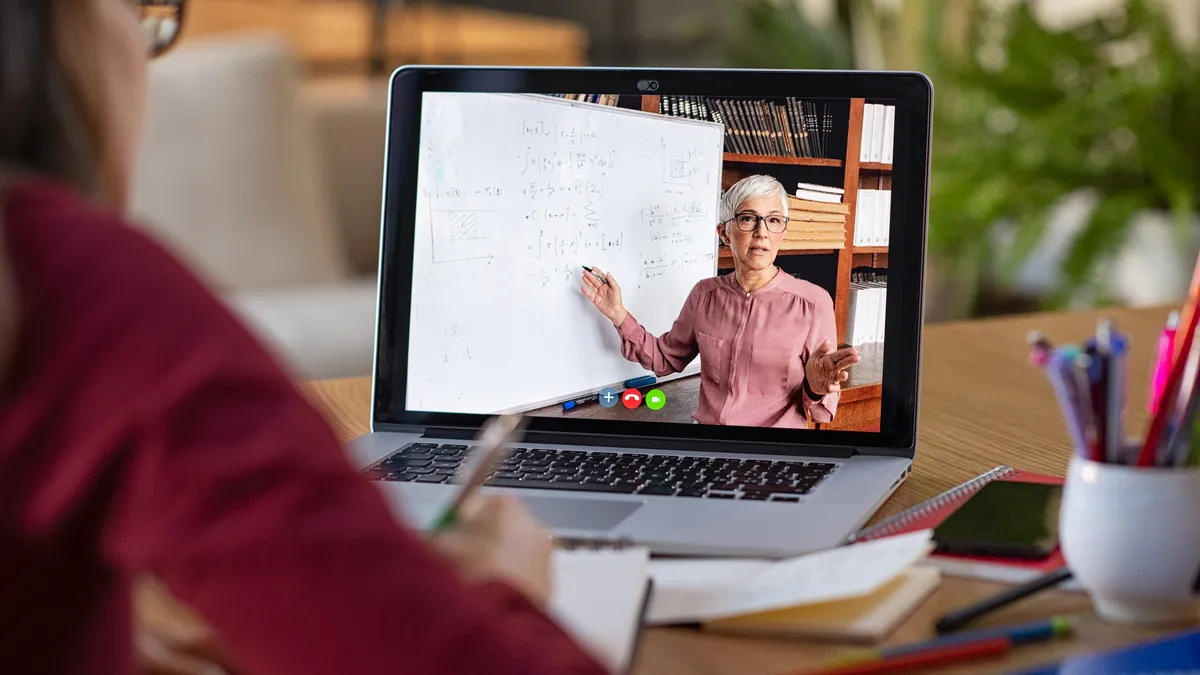

When the novel coronavirus pandemic forced schools to shut their doors and transition to virtual learning, it not only necessitated a change in the medium and location of delivery, but in the thought processes behind how things are done. The result is a system that still has its share of bugs to work out, but one that stands to have lasting effect on school models long after COVID-19 wanes.

We looked back at a handful of our Curricular Counsel conversations from this year to provide a fuller picture of how things have changed and what challenges persist.

Navigating vendor pitches challenging as ever

Even before the pandemic made access to devices and home internet a basic necessity for all K-12 students, the process of navigating pitches from vendors for the plethora of platforms, tools and resources on the market was a feat not for the faint of heart. The focus for most district curriculum chiefs nationwide has long been to look beyond the shiny promises of a product being the most high-tech and exciting on the market to get to the root of how that tool or resource will help students engage and create with material in ways not possible without the technology.

This year has only honed that focus, but the nature of such a sudden shift also required some wiggle room.

"I will say the ones that we're looking to add are probably not the ones that lend themselves to creativity or innovation as much as others, but that was the gap that we had," Maureen McAbee, assistant superintendent of instruction for Community Consolidated School District 59 in Elk Grove Village, Illinois, told K-12 Dive in October. "We do focus on innovation and creation and collaboration, yet when we're in a remote environment, because we have a blend of synchronous/asynchronous [learning], we need a product that really is more skill-focused to allow kids to continue to practice at their level — which the teacher, when we’re in-person, can do."

McAbee said her district tends to test out new platforms, tools, resources and methodologies during summer learning programs, when educators feel they have more flexibility to experiment. This summer, it tried three tools and adopted all as additional resources for the current school year.

This year was also seen by many as a chance to maximize value and potential of digital tools to meet the needs of all students. "This is where, while it's unfortunate that we are facing COVID, a crisis has led to some great opportunities," said Clay Hunter, associate superintendent of curriculum and instructional support for Georgia's Gwinnett County Public Schools.

"You have these digital tools, and parallel to these digital tools, research has been quite clear on the things you need to do in order to make sure you have an effective lesson," he said, noting that the tools still require an effective plan for success. "You need an activating strategy to help students with prior knowledge versus the knowledge they're about to acquire. You need a mini-lesson where you can model for the students what you expect for them to know and be able to do. You need an opportunity for those students to be able to collaborate with both the teacher and their peers to deepen their understanding."

One area where he sees remote learning's value in this space lasting is in video lessons students can repeat if they didn't understand a concept, as well as tools that let shy students ask a question without the risk of embarrassment.

"Now, there's this equity and voice because students can actually click a button and answer very quick, and the teacher can see who answered it correctly or incorrectly and help them with their misconception, without any other child knowing," said Hunter.

New assessment models considered, but tricky

With no reliable way of traditionally assessing student learning in a remote environment, states were forced to abandon their annual standardized assessments in spring 2020 as the U.S. Department of Education issued waivers from federal accountability for that school year. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos would later advise districts to take time to "rethink" assessment practices while also noting waivers would not be issued for 2020-21.

And even without waivers for this school year, flexibilities are on the table. As a result, the exploration of alternative approaches is on the upswing.

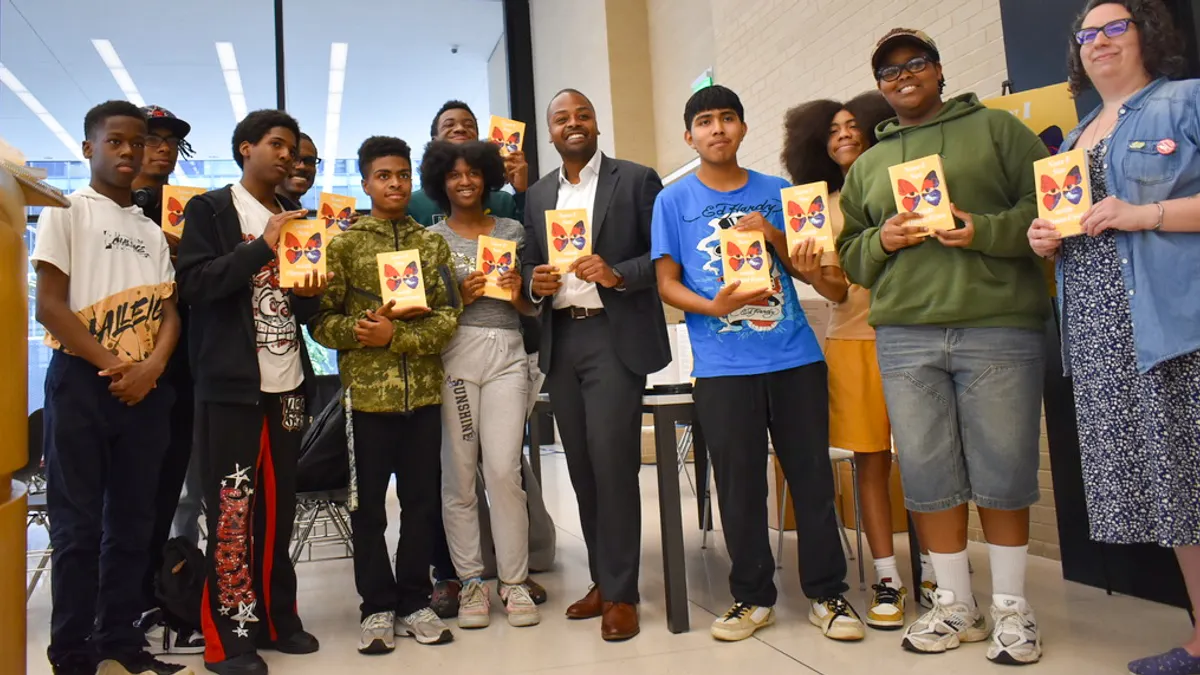

Antonio Burt, chief academic officer of Shelby County Schools in Memphis, Tennessee, said in September the state provided a diagnostic assessment that only focused on grades 4 and above, in addition to looking at the previous grade's standards. He also said all K-8 students universally had to take the iReady diagnostic, "as opposed to previous years where we only did the kids who fell in the bottom 15%," to really get a good idea of where key learning loss was.

He also said the district created its own in-house, standards-based assessment. "Our own district diagnostic looked at what we call power standards — those standards that are heavily weighted based on end-of-year assessment [subjects] considered the major work of the grade," said Burt. "We created a diagnostic centered around those from the previous school year for all kids so we can know what standards that carry from one grade to the next our kids didn't master. We're building supports around a result from those prior to our formative assessments."

In a similar vein, Mike Lee, assistant superintendent for academic programs and professional learning at Buckeye Elementary School District in Arizona, said, "What we do have good ability to do is more formative stuff, assessment to help plot what's next. That's what we focused on with our teachers. So how can you more effectively figure out where a student is so you can figure out what to do next? You can do that virtually."

Many districts also embraced mastery-based or competency-based approaches. For some, these approaches have taken the form of project-based models.

"That has been the more tricky piece with it. Our assessments in our units are a performance-based task of some sort requiring the student to display or demonstrate the skills of the unit as well as these learner outcomes that is assessed on a rubric," McAbee said. "We can see how the student is growing [but] how they performed doesn't translate as cleanly into a data set like a standardized test would."

While that qualitative data can take more time to process than quantitative results would, "it does allow us to look at where is this child falling within problem-solving and then what can we do to get the child to the next level," she said.

Professional development adapts to overcome

Just as the way students received lessons changed, so too did professional learning opportunities for educators.

"As educational leaders, we sprinted to support teachers with ideas, lessons and support. But now, a month into remote learning, it’s no longer a sprint; it’s looking more and more like a marathon," Matthew X. Joseph, director of curriculum, instruction and assessment for Leicester Public Schools in Massachusetts, told Education Dive in May. "Technology trainers need to create a long-term plan to support educators and encourage the effective use of digital tools for instruction."

Online meetings and digital communication have become the norm for providing learning opportunities to educators now. Having strategies for virtual training will make these opportunities more impactful.

In Illinois' CCSD 59, McAbee said, "Some of it was directed, some was self-directed. Some of it was synchronous, some of it asynchronous. But it was some common modules we wanted all teachers to have. For example, “What does a mini-lesson look like in remote learning?”

Her district also used its summer school period this year to hone the PD model it wanted to continue utilizing during remote learning. "We brought in those summer school teachers and our instructional coaches to lead the professional development in August because they became our experts," said McAbee. "They had a chance to try it out and say, 'This is what works for me. This is what didn't work. That was very helpful. The five days was very helpful.'"

"I noticed with remote learning, since it is new for everyone, even those who might not have been eager to work with a coach in the past were eager to work with a coach and get that support," she continued. "It kind of leveled the playing field. Nobody was an expert at this, really. We're all on the same page. We’re all learning together."

Dive Awards

Dive Awards