Dive Brief:

-

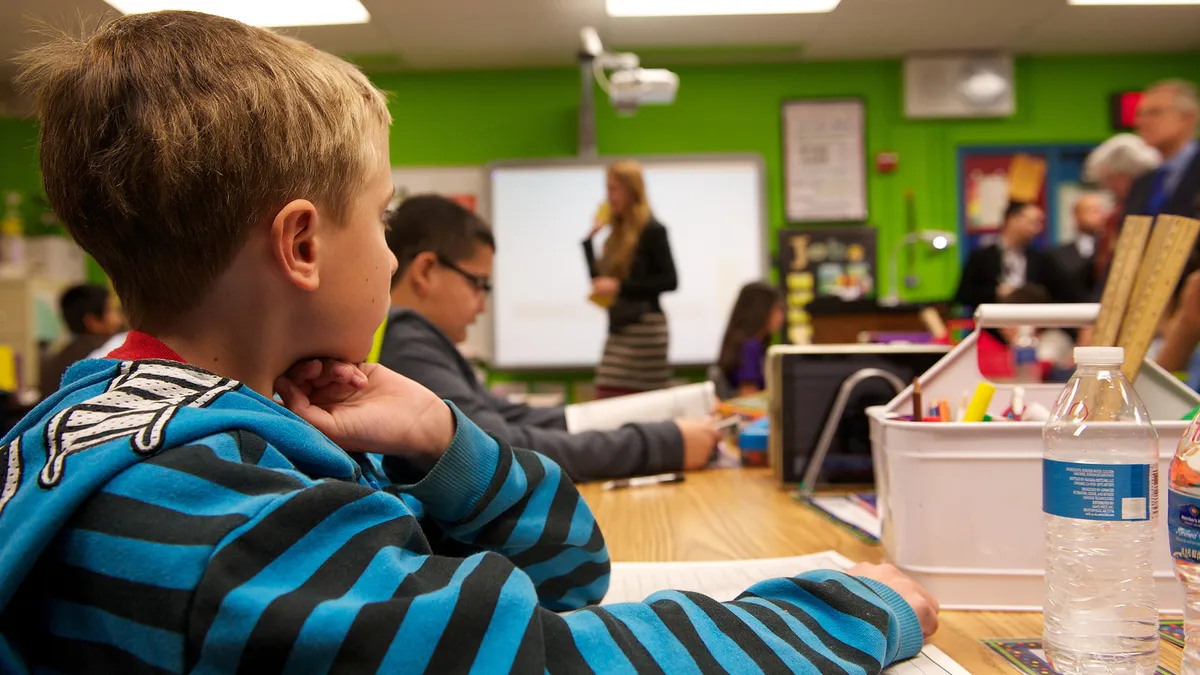

Students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) struggle with the distractions and lack of scheduled exercise in remote learning environments, NPR reports.

-

Most homes don’t have designated distraction-free learning spaces, and parents are often busy working or looking for work, Haftan Eckholdt, a developmental psychologist and chief science officer at the nonprofit Understood, told NPR. Students with ADHD also benefit from breaks, similar to recess, that allow them to release energy.

-

Some students with ADHD do well working remotely because they are less distracted by their peers, but educators are also contending with the excitement and rewards that come from activities like online video games, which provide competition for their focus on remote lessons.

Dive Insight:

Children with ADHD often do better in the structured school environment, where there are consistent transitions and other students off which to model their behavior. They are also surrounded by educators who can help manage their behavior and provide social-emotional support.

At home, parents can emulate this setting by carving out learning spaces in specific distraction-free zones that are easy to monitor. Morning huddles can help students set a plan for the day so it’s not so overwhelming, and parents can help their child stay on track by giving them, for example, sticky notes with 25-minute tasks such as “do math problems one through 12.”

Consistency is also important to foster success. Teachers should schedule class video sessions at the same time every day to provide structure and help students plan their day. Teachers can also text and call students to give them the types of prompts they would provide in-person in the classroom. And they can establish specific learning targets for individual students, rather than the class as a whole.

Even during in-person learning, most very young students with ADHD are not ready for school. Four- to 5-year-old students with ADHD symptoms are seven times as likely to lack social-emotional skills than those who don’t have symptoms, according to a Stanford University study in the journal Pediatrics. They are also six times as likely to have impaired language development and are more likely to have low assessment scores on approaches to learning, such as taking initiative, self-regulating and showing creativity. They did, however, score the same in the study in the areas of cognition and knowledge.

Twice-exceptional students — those who score high in academic aptitude tests but also have ADHD, mild autism, dyslexia or other learning disabilities — may require even more resources to be successful with remote learning, learning experts say. In a typical classroom environment, these students tend to struggle, but new technologies and resources may help them succeed in inclusive environments. Approaches such as Universal Design for Learning also offering flexibility that may allow for more students to learn together despite their differences.