In 2018, there has been, on average, close to one mass shooting in the U.S. per day.

If that statistic, from the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive, wasn’t shocking enough, guns have killed or injured more than 2,700 people under the age of 18 this year, their data shows. In many cases, these deaths and wounds are associated with a school shooting.

The aftermath of major student massacres — like that in Parkland, Florida, or Santa Fe, Texas — has left members inside and outside of school communities to grapple with the everlasting question that has catapulted to the center of the nation's attention: How do school and community leaders prevent this from happening again?

Typical answers usually involve stricter gun control policies, hiring more school resource officers or arming teachers. But there’s something even more fundamental — the design of the school building.

Whether creating a structure from the ground up or updating what’s been built, stakeholders are being tasked with a new challenge of designing safer schools, especially during an era where school shootings and other violent incidents have led parents to fear for their children's welfare during the day. It’s no simple project — not only do experts need to bump up security measures, but they also can’t forget they're building a school, not a harsh, prison-like space.

"What's happened is this kind of dichotomy where school safety and a welcoming design are juxtaposed, and oftentimes school safety is termed as hardening. I like to take the two terms and show people that they’re actually one and the same," architectural designer Jenine Kotob, who helped design multiple school building projects in Washington, D.C., said in an interview. “School safety does not inherently have to be ugly or hard — oftentimes, enhancing safety can assist in beautifying a school."

Developing the architectural blueprint

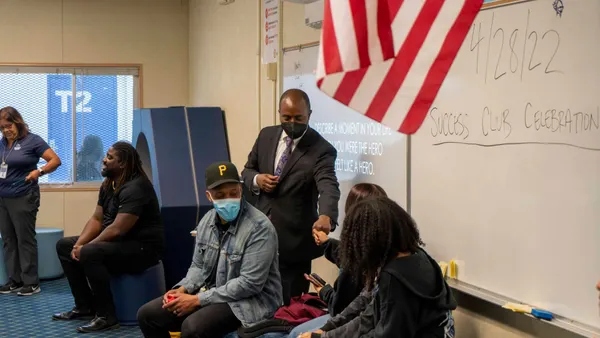

As part of its national tour, the Federal Commission on School Safety, which President Donald Trump formed in the aftermath of the Parkland shooting in February, visited the Miley Achievement Center in Las Vegas, which is nestled in Nevada's Clark County. Miley serves students in elementary, middle and high school, and is geared toward those with behavioral challenges.

This year, Miley was awarded a grant by ASIS International, a security management company, for upgrades to boost school safety. But when it was built in 2005, years before the widespread rise in hi-tech surveillance equipment, architect Thomas Schoeman and his team were tasked with building a safe school from the ground up.

And in designing the school’s blueprint and executing it, Schoeman said striking a balance between safe and welcoming was “especially important” considering the school’s population.

Designing the building was all about balance. The colors of the walls had to be engaging, but nothing too harsh. The building’s shape had to set boundaries for the students in each school without making it too difficult and overwhelming to get around. Courtyards provide glimpses of natural light, while other areas use more artificial lighting. Students had to feel welcome, and they — along with teachers and staff members — had to be safe.

“We deeply believe that a physical environment is critical in keeping schools safe,” Miley principal Joanne Vattiato said during the commission’s school visit.

But if a safety threat ever came up, the school had to be prepared. So Schoeman and his team took extra steps to ensure that was the case: They built small common areas between classrooms, allowing a teacher in one classroom to access another room — good for when one student might be acting out, requiring extra help — without using its main door. Small, isolated rooms set aside space for students who need some alone time, he said. And there was limited entry, making it easier to control who goes in and out.

“Wherever people gather is an enemy target,” Schoeman said in an interview. “In the architecture community, we feel that the design of schools has a big role — it can greatly enhance the safety of students.”

Kotob understands the gravity of that idea on a professional level, as well as a personal one. She was studying architecture at Virginia Tech in April 2007, when a shooter launched an attack on campus and left 32 dead — including one of her close friends. The experience transformed her interest in architecture, centering it on its intersection with schools and education. So when she helped design multiple D.C. school projects, including the Marie H. Reed Community Center, she made sure to keep the students attending it in mind.

The renovation project started with an existing building, an "inward focused, big, brutalist, concrete structure" constructed in the 1970s as a school, Kotob said. It had few windows and plenty of vulnerable entrance points, and there was no way to monitor who went in or out. Post-redesign, the school and community center has plenty of natural light, fewer access points, integrated alarms and a public address system that reaches classrooms, offices and hallways.

"We’ve been able to ensure that that level of quality is something that even an existing building can receive," she said. "And we improved the design quality through very simple gestures."

Engaging local police, other organizations

At the commission’s final listening session, stakeholders emphasized that no entity can act alone in solving the school safety puzzle. Instead, they said, officials across departments and disciplines must work together and make sure all relevant groups are involved and have a voice at the table.

In Nevada, state law helps make that a reality. Since June 2017, district and charter school officials in that state have been required to consult with certain groups, like law enforcement or emergency management, before “constructing, expanding or remodeling buildings for schools or related facilities or acquiring sites for those purposes,” the law says. It also states districts in certain counties must appoint an emergency manager.

In Clark County, the school district collaborates with a 24/7 police force, with some 170 officers. Chief James Ketsaa said having a dedicated police force certainly benefits a district, but it’s the connection police have to the schools that’s the most important. When officers have a good relationship with a school, they’re more likely to know the campus layout and safety protocols, and they know the student body and school staff.

“We know the unique needs of the school district,” he said. “We know the layouts of all the schools, and we know the students’ mindsets and how they think. It’s all those intricacies.”

On a day-to-day basis, it can be hard for school leaders to handle everything on their plates. Adding safety priorities to the mix didn’t make it any easier. That led to organizations like CharterSAFE, a nonprofit that provides California’s charter schools with self-insurance and risk management services.

“School leaders are so overwhelmed a lot of times,” CharterSAFE CEO Thuy Wong said in an interview. “We’re here to protect member schools and keep them safe. Holistically, whatever we can do — that’s what we’re here for.”

Outside resources are helpful in safeguarding school communities, but it’s important to involve the community itself in the move to create a secure school. A big part of an architect's process, Kotob said, is participatory design, which allows all relevant voices to have the chance to contribute. In working on D.C. school design assignments, she said teachers typically asked about things like classroom door hardware, while parents — in addition to asking how the site will be made safe — wondered about traffic patterns, open areas like playgrounds and how the project would change their daily routines.

"We’re holistic thinkers," Kotob said. "We want to allow all the various stakeholders to be sitting at the table, so we can talk to them about what fears they have and unpack them."

Working with community members also means involving students, who can serve as ambassadors to report potential threats, consultants in creating safety protocol, or another set of eyes and ears who can also talk to school officers when they don’t feel safe.

“I think a lot of times as adults, we get caught up in our jobs and things and we forget about that — we forget about the kids,” Ketsaa said. “That insight is incredible.”

Creating small fixes for small budgets

School budgets, however, are tight and have not recovered since the recession. Federal funding has been deemed inadequate, state funding has plummeted, and local funding doesn’t compensate. So, while spending for school safety measures seems necessary to many, it’s not that easy to find the funds for pricey surveillance equipment.

But there are smaller and cheaper — yet still effective — things schools can do to boost safety during an attack or to prevent one in the first place. In schools with small children, having toys close by can keep them from crying or drawing attention to themselves when it’s important to stay quiet, Wong said.

She added that practicing finding hiding spots with young students could make for a fun game that helps teachers think of safe areas they might not have thought of before. And several free, online resources that administrators might not be aware of, detail strategies schools can use to keep members of the community safe, Wong said.

“There are two viewpoints out there — idealistic and realistic. Idealistic is, ‘Everyone should have this plan.’ But we don’t live in an ideal world,” she said. “Realistically, you say, ‘What can we do to make schools safer? You can say, ‘This is going to go in the budget for five years,’ and do what you can.”

For Mike Wilson, Clark County's district director of emergency management, taking an all-hazards approach to school safety is essential to prepare for any type of emergency. Another way to make sure responders are prepared: inviting them to do a safety walk around the school to get the lay of the land. For the former elementary school principal, “we need to have access to the buildings.”

Preparing for more than school shootings

Despite the amount of attention they command each time they appear in the headlines, in reality, school shootings are extraordinarily rare. Students are more often threatened by bullying, harassment or sexual violence.

One-third of students report being bullied, and some studies find that roughly four out of five children and teens in the U.S. report being sexually harassed at school. And it’s not just students who face these issues. Some 20% of educators say they face sexual harassment or assault in the workplace, and even more who experienced or witnessed it didn’t come forward out of fear for their career or safety.

In certain areas, natural disasters are also a regular occurrence. As a result, new schools are required to have storm safe rooms, and schools have worked to improve preparedness efforts.

“The preparedness … is key, and that's what we have been working on for the last couple of years,” Marilyn Lewis, the Alabama State Department of Education’s prevention and support services coordinator, said during the federal commission’s final listening session on Aug. 28. “Let's get in front of the cart. The pain is not as difficult to feel as if a wagon is running over us because we're always behind it.”

So, when designing a school, all these types of things have to be considered, Wong said. For active shooter scenarios, it’s important to close rooms and windows, but in preventing opportunities for other unsafe situations, keeping rooms open is the better option, she said. And put simply, there’s not much that isn't woven into school safety discussions.

“Everything is related to school safety,” Wong said. “When you’re talking about campus design, you have to talk about all of it.”