Dive Brief:

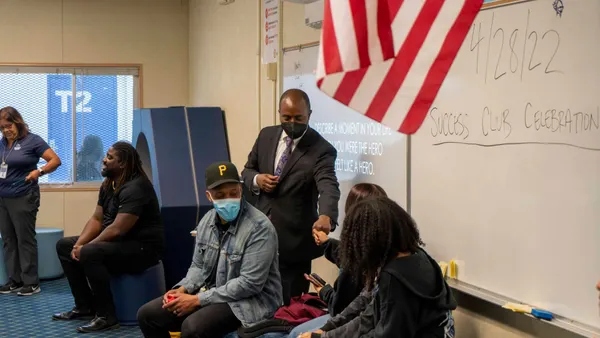

- School systems nationwide are working to provide greater support for students with incarcerated parents, as research shows kids with a parent in jail are less likely to graduate from high school or attend college and more likely to suffer from behavioral problems, repeat grade levels, and become enrolled in special ed classes.

- The issue calls attention to disparity in the nation's schools as well as its criminal justice system, with black students 7.5 times more likely than their white peers to have a parent in prison — and District Administration reports that 25% of black children had an incarcerated parent at age 14 in 2014.

- In the San Francisco Unified School District, all middle and high school counselors participated in Project WHAT! (We’re Here and Talking) sessions in 2014-15, hiring youth who have incarcerated parents to lead trainings and presentations about their experiences for school staff and students.

Dive Insight:

Programs like Project WHAT! empower students and give them an opportunity to lead, helping educators and administrators start to identify some of the factors that lead to achievement, race, and discipline gaps in U.S. schools. It's important for school staff to account for their discipline record, including at the earliest stages. As many as 8,000 pre-school age children face punishments in school that include suspensions and expulsion, and a 2005 report showed that 3- and 4-year-olds were expelled from pre-k programs "more than three times as often as students in kindergarten through high school." Black children were suspended twice as often as their white and Latino peers.

Accountability is key in identifying and proving the existence of disparity. In Washington, a state report tracked overall suspension and expulsion rates, finding that young black students are punished much more than white peers. In the 2014-15 school year, The Seattle Times reported, 10% of students removed from classrooms were black, though those students made up less than 5% of the total. A "discipline gap" between how minority and non-minority children are treated also applies to disabled students, who are "suspended at two to three times the rate of non-disabled students."

Punishing nonviolent behavioral offenses with harsh measures like suspension feeds a phenomenon called the school-to-prison pipeline, in which minority students are disproportionately ending up in U.S. jails after receiving punitive treatments in school that cause them to disengage and drop out. California, Illinois and Minnesota are experimenting with possible solutions that help preventing the pipeline from becoming standard, in an attempt to halt the greater cycle of incarceration and poverty.