In the six decades of Head Start's existence, it has served nearly 40 million children and their families. But supporters and alumni are quick to point out that the program for children from low-income families provides more than preschool opportunities.

"It is more than child care and early learning, it's a lifeline for children and families in our communities who face the steepest hills to climb to achieve success in school and in life," said Yasmina Vinci, executive director for the National Head Start Association, during a call last month with hundreds of supporters and advocates. The association represents program leaders, children and families.

Head Start serves children from various backgrounds

"If we want to build a healthier, freer and more fair America, we have to start by giving every child a real shot, regardless of circumstances at birth, a head start in life, and that's why programs like Head Start matter," Vinci said.

The call was held to rally opposition to an anticipated request from the Trump administration to eliminate Head Start in the fiscal year 2026 budget request. However, despite those reports, the program was not dropped in the top-line FY 2026 budget proposal released May 2. A more detailed budget proposal is expected within the next month.

The Trump administration has been cutting spending across federal agencies to reduce what it considers waste and to give states more fiscal authority. Some Republicans in Congress and other critics have called Head Start unsafe and ineffective at boosting children’s academic performance.

But NHSA and other Head Start supporters point to research and anecdotal stories demonstrating positive academic, social and economic returns from the long-time program

When President Lyndon B. Johnson announced the launch of Project Head Start on May 18, 1965, he said rather than it being a federal effort, the program was a "neighborhood effort."

Head Start funded enrollment grew over past 60 years

Today, Head Start serves nearly 800,000 infants, toddlers and preschool children a year. More than 17,000 Head Start centers operate nationwide. A companion Early Head Start program provides prenatal services.

As the 60th anniversary approached, K-12 Dive spoke with three women who spent their preschool years in Head Start programs in the 1970s. They reminisced about supportive teachers, tasty meals and favorite songs. They also shared how that educational foundation impacted their life journeys, including how they still hold connections to the program.

Sonya Hill

Sonya Hill's connection to Head Start has been a full-circle experience — from her participation as a child living in Orlando, Florida, in the 1970s to her role today as director of the area's same Orange County Head Start program.

Hill, 52, has vivid memories of her own Head Start experience. One of her favorite activities was when all the children held onto the ends of a colorful parachute. They would shake it and run under it. Another special moment came when her father, who worked in a bakery, visited her class for a special event featuring community helpers — and brought doughnuts for all the students.

Her favorite teacher, she said, was Shirley Brown.

Years later, right after graduating from South Carolina State University with a degree in social work in 1994, Hill was waiting to be interviewed for a job at a Head Start program. Somehow she hadn't made the connection that this was the same program she had attended as a child. And then Brown walked around the corner.

"I hugged her so hard. It was the same feeling of hugging her when I was in her Head Start classroom, and I couldn't believe it," Hill said.

Hill got the job, and for the past 30 years, she has worked in various roles there, eventually being named director in 2016.

As leader of the program, she travels to the Florida state capital and to Washington, D.C, to advocate for Head Start services, telling lawmakers about former students who have gone on to college and careers.

"I'm just thinking this is a program that has impacted so many people across the United States, but I know firsthand that Head Start works," Hill said.

She credits her childhood Head Start experience with helping her become the first in her family to graduate college and also to earn a master's degree.

Her family — which she notes extends today from her grandmother to children of her nieces and nephews — is "extremely proud" of her, Hill says, and she doesn't take that lightly. "I know I have a lot of responsibility to my family, to my community," Hill said. "Head Start truly gave me my foundation, and that's why I've stayed here, because I owe so much to the program, and I get to see firsthand how it's changed lives."

Toscha Blalock

As a young child growing up in the small town of Monessen, Pennsylvania, Toscha Blalock's home life was fun and welcoming, but hectic. She lived with nine relatives, including her mother, Gloria Anderson, who had Blalock when she was a teenager. As the youngest, Blalock remembers the adults and her cousins caring for her by braiding her hair and playing games with her. Even at a young age, her family labeled her "the smart one."

But the family struggled financially, she said. Her mother, who had negative experiences as a student during desegregation efforts, sought out the area's Head Start program for her daughter, determined that she would have a better education.

As a Head Start student in the 1970s, Blalock loved reading books. She also enjoyed the school day routines of learning, meal time and napping. By the time Blalock was ready for kindergarten, she was reading above her age level. In 1st grade, when she wasn't included in the highest level reading group, Blalock's mother spoke to school administrators, and the young student moved to the higher level group.

"There were a lot of experiences like that in the school. There was a challenging racial dynamic in the town, and I think that spilled into how children were treated," said Blalock, 53.

In high school, Blalock was one of only two Black students in her 89-student graduating class enrolled in college prep classes.

After graduating from Temple University in Philadelphia, with degrees in psychology and education, she began working as a research assistant. A few years later, she participated in a research project evaluating a new statewide quality initiative for early childhood education. As a then-new mom and a researcher, she recognized gaps in quality and availability in early childhood education, as well as the high price of child care.

"From that point, my entire career stayed in early childhood education," Blalock said. She went on to be a senior leader for an Early Head Start program in the state and to earn a master’s degree in organizational and strategic leadership.

Today, she is the chief learning and evaluation officer at Trust for Learning, a nonprofit that helps expand high-quality early learning experiences for children nationwide, including those in Head Start. The trust's Ideal Learning Head Start Network aims to help Head Start programs access innovative and effective curricula, classroom spaces and other program components.

For example, she described an Early Head Start program in Austin, Texas, that is taking a Montessori-type approach to home visits and showing parents how to use items around their home as learning and developmental tools for their children.

Blalock’s own childhood experience is never far from her mind as she visits Early Head Start and Head Start programs across the country.

"I know my life would have been different without that early investment," she said. "That's something that I want for every single child in America — to have that opportunity."

Michelle Brown-Grant

Michelle Brown-Grant attended Head Start in the early 1970s in New York City, and she can still remember the joy of going outside to play on the playground and how the teachers didn't force her to change from being left-handed, as used to be common.

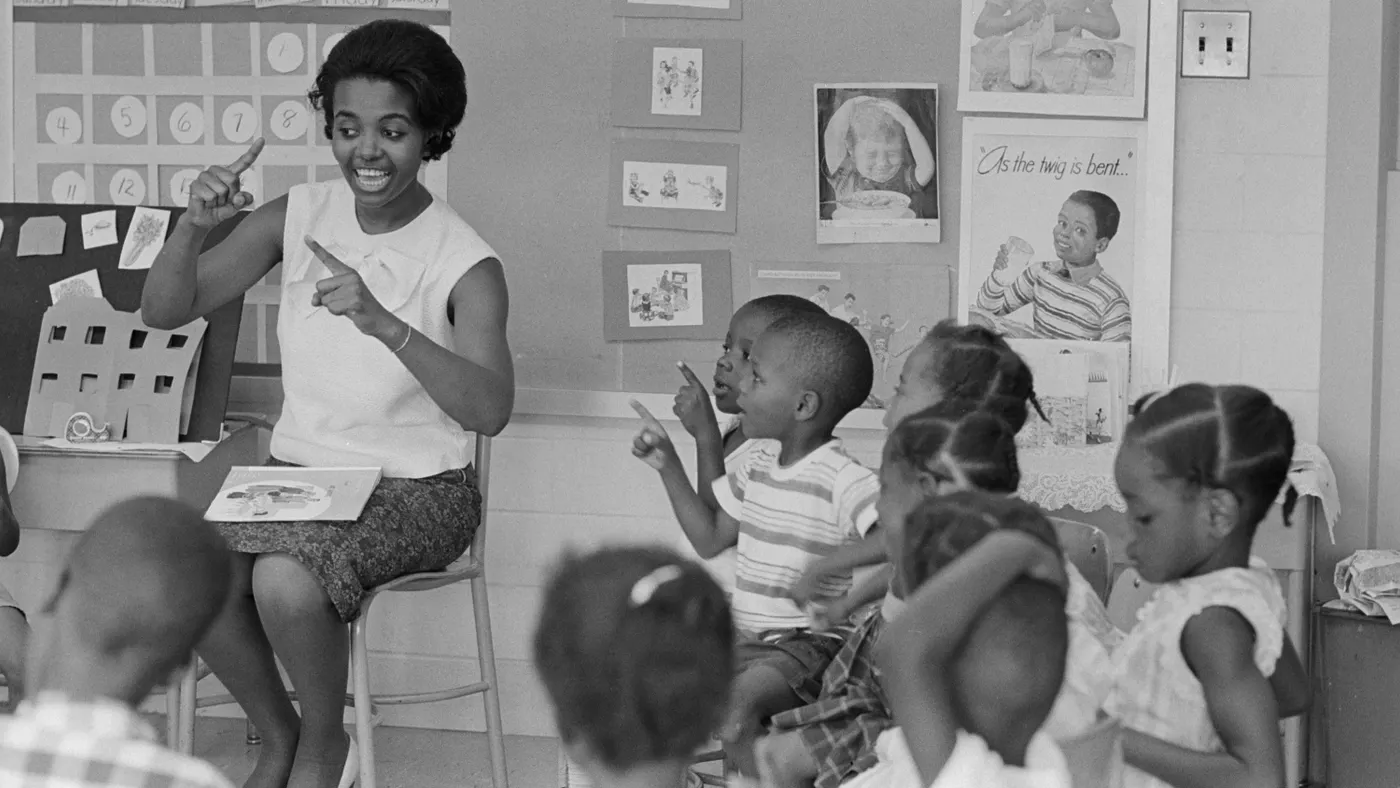

She also recalls how her teachers lived in the community and were Black — just like her.

"Representation does matter and seeing images of yourself as educators helps with your blueprint," said Brown-Grant, 58.

Her family was low-income, but their house was full of books — and Brown-Grant loved to read at home and at her Head Start program. From a young age, her godmother who raised her, Gladys Beaulieu, predicted she would grow up to be a teacher. So did Brown-Grant herself, who would play school by lining up her dolls and teaching them lessons with the help of her "teacher's assistant" — her older sister.

Brown-Grant continued to enjoy books in school and, by 6th grade, was reading at a 10th grade level. She graduated third in her high school class and enrolled in Cornell University in New York. She planned to study law but pivoted to education when a professor said Brown-Grant had a gift for teaching.

She graduated from Cornell in 1988, becoming the first in her family with a college degree. She taught 3rd grade at her former elementary school, and over the next two decades worked as a teacher and school administrator — including as director of curriculum and school principal.

She is currently an instructor and coordinator of education at Bloomfield College of Montclair State University in New Jersey, as well as an educational consultant with the Ideal Learning Head Start Network.

Brown-Grant has earned two master's degrees and expects to complete her doctorate in education in the next few months.

She says her Head Start experience prepared her to be successful in school. "When you have a solid foundation, it just opens up windows and doors for you that nobody could take away," she said.

Brown-Grant attributes her early involvement in Head Start to also benefiting her family. While she attended Head Start, her godmother began volunteering in the classroom. Later, Beaulieu worked as a lunch aide and paraprofessional at Brown-Grant's elementary school and eventually earned her bachelor's degree and became a teacher herself.

That support for children and their families is what keeps Brown-Grant passionate about her continued work with Head Start.

"I love going into Head Start classrooms and spending time getting on the floor with them and just being immersed in that energy," Brown-Grant said. "It just really gives you hope for the future.”

Clarification: This story was updated with the full name of the institution where Michelle Brown-Grant teaches.