Using data to help guide decisions about increasing student engagement, providing extended learning opportunities, and finding effective ways to communicate with parents and students can help boost attendance rates as students adjust to full-time, in-person learning, panelists said during a Wednesday webinar hosted by Attendance Works and the Institute for Educational Leadership.

The timely analysis of attendance data can pinpoint effective practices, as well as identify barriers to school engagement for individual students and student subgroups. Low attendance rates should be seen as an early warning sign that positive learning conditions are missing, said Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works.

“If we want to improve attendance or reduce chronic absence, we have to understand and address those factors that are contributing to chronic absence in the first place,” Chang said.

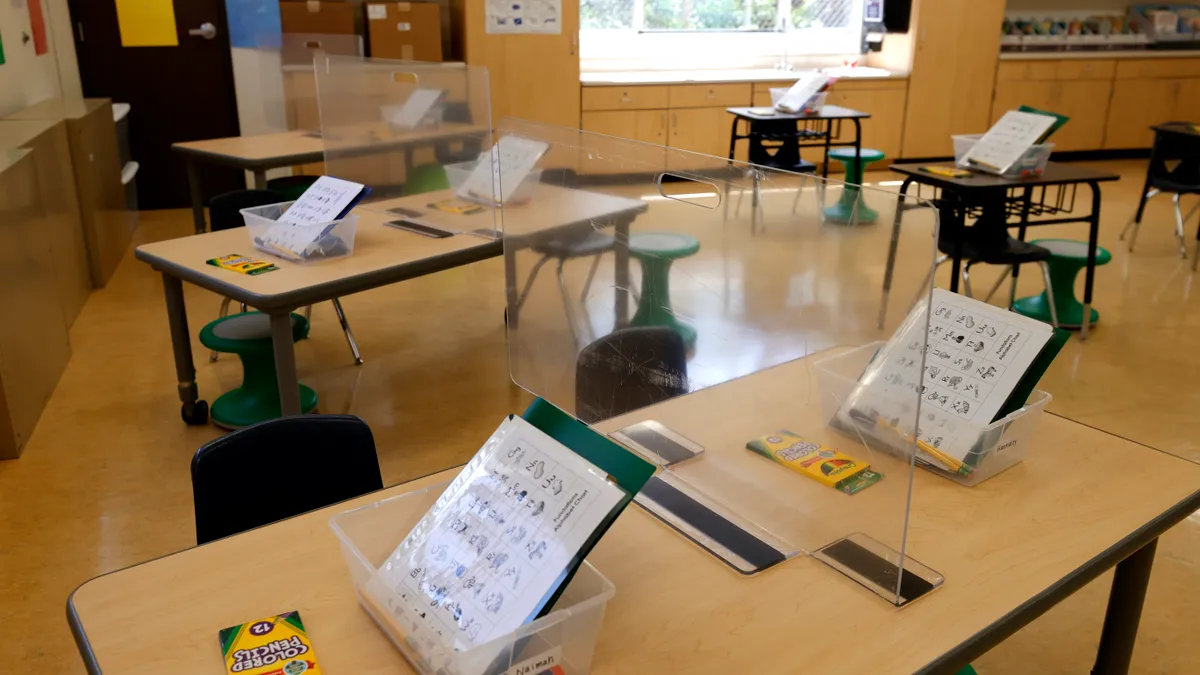

The 2021-22 school year was supposed to start smoothly after a year of remote and hybrid learning, but student quarantines due to COVID-19 close contacts and the ongoing pandemic are disrupting school attendance rates, causing school leaders to take more comprehensive and thoughtful approaches to prevent student absences and recover lost instructional time.

Pre-pandemic concerns about chronic absenteeism rates only worsened during the 2020-21 school year as many school systems shut campuses for in-person learning, only offered hybrid learning, or had families who chose to have their children learn remotely.

Younger students and students from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as those living in poverty, those with disabilities and English learners, had “distressing” rates of absenteeism during the pandemic, according to a report by FutureEd published in May.

Students who are chronically absent are at academic risk, and their absences may be due to school barriers, aversions, disengagement or misconceptions, according to Attendance Works.

There are, however, strategies school systems can use to lessen chronic absenteeism, which is defined as a student missing 10% or more of school for any reason.

Create positive relationships

Building strong, trusting relationships between school and homes was important pre-pandemic, but it’s even more critical now, said S. Kwesi Rollins, vice president for leadership and engagement at Institute for Educational Leadership.

Schools should make sure families and staff feel safe and supported by being empathic to their needs, as well as taking a positive, problem-solving approach to individual circumstances, Rollins said. “Now, more than ever, we need strong relationships and in many cases we need to repair relationships.”

Let data guide interventions

The Connecticut Department of Education began collecting consistent and reliable attendance data early in the pandemic so it could identify areas of concern.

As a result of the department’s data collection efforts and partnerships with the governor’s office and regional educational service centers, the state launched the Learner Engagement and Attendance Program, which targets support to 15 districts based on multiple data points.

The program also organizes home visits to individualize engagement solutions for families. As of Sept. 13, more than 2,400 home visits have been conducted, said Connecticut Commissioner of Education Charlene Russell-Tucker.

“Attendance is a precursor to engagement, and engagement is a precursor to learning, and so that's critically important,” she said. “If we don't get that right, we won't get to where we need to go.”

Build a team response

Russell-Tucker also highlighted Connecticut’s efforts to support district programs for student social-emotional wellbeing and trauma response. The state's education department is also working collaboratively on resources with its Department of Public Health, Office of Early Childhood, and Department of Children and Families.

Additionally, the state hosts Talk Tuesdays, which bring district leaders across the state together virtually to discuss student attendance and engagement monitoring efforts and interventions.

At the school building level, attendance teams could include nurses, counselors, special education staff, a family resource center director, teachers, administrators and more, according to Attendance Works.

Set up different pathways for engagement

Maribel Childress, superintendent of Gravette School District in Arkansas, said school quarantines have disrupted plans to have most of the district’s students back to school in-person, full-time and consistently. In response, the district has developed protocols to make sure students who need to stay home temporarily are able to stay on track academically.

Some of those approaches include having a “Quarantine Catch-up” referral program, after-school tutoring by individual teachers or by subject area, learning recovery sessions on weekends, and synchronous and asynchronous learning opportunities.

“We're going to keep plugging away, and we're going to keep working with our students until the teachers tell us that the student is where they need to be, that they have the work done, and they are ready to be successful,” Childress said.

Have a tiered approach

In an effort to organize attendance interventions, schools can use a tiered approach that provides foundational supports to all students and increases with intensity for students in greater need of individualized attention.

The foundational supports include having whole-school positive relationships, routines and rituals, Chang said. “What happens at the foundational level is absolutely critical.”

Focus on transition grades

If school leaders are unclear of where to start for attendance analysis or interventions, it’s a good idea to look at data for the transition grades, which can include kindergarten and 6th, 9th and 12th grades, advises Attendance Works.

Through its data, the Gravette School District discovered attendance concerns for its kindergartners, 9th-grade students and students whose parents worked night shifts. As a result, the district has extra layers of monitoring of those students’ engagement levels, said Childress.

Make communications clear and brief

Very few people read every word of a school district’s communication, and that’s why it’s important that critical messages are accessible and condensed, said Todd Rogers, professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Messages can be sent in a variety of formats, including email, in-person, text, a paper note in a student’s backpack, robocalls and more. But if the district is sending written communication, it should:

- Have as few words as possible.

- Have clear requests and directions for responding.

- Be written at lower reading levels.

- Be in languages families speak at home.

- Be formatted so the message is easy to skim.

“In addition to just being more likely people will read and respond to what we send them, or what we communicate to them, it's just kinder to people to write in a way that is more accessible,” Rogers said.