Strong parent-school collaboration can result in a host of benefits, from expanded equitable learning opportunities to improvements in students' academic and social growth.

But getting there can be easier said than done.

Recent research from NWEA, an assessment and research company, found several common roadblocks to family-school partnerships. The organization highlighted the need for improved collaborations — especially as schools continue to recover from COVID-19-related setbacks — and offered strategies to strengthen family-school connections.

Schools shouldn't "ease off the pedal" in providing academic and social-emotional interventions to students and in prioritizing family-school relationships, said Ayesha Hashim, a senior research scientist at NWEA and coauthor of the report on family engagement with schools.

"Family engagement is another way to really hone in and really support students and give them the conditions they need to thrive," Hashim said.

Schools may approach family-school engagement with a deficit-based viewpoint focused on a student's poor academic performance or based on individual attitudes about relationships. But NWEA suggests schools take a more collaborative approach to benefit all students, families and the school community.

In its research, which was based on existing studies and surveys about post-pandemic parent engagement, NWEA identified these three common barriers to family engagement — and steps schools can take to overcome them.

Assuming a lack of participation is a lack of interest

Families should be viewed as equal partners with educators and valued for their assets, strengths and leadership potential, the NWEA report said. However, if families don't respond to traditional forms of school outreach, educators might assume they are not interested in engaging.

Yet that's not always the case, Hashim said. There could be a host of logistical and practical barriers — including societal, individual, family related, or school-related — that make it difficult for families to engage in activities such as tutoring.

Educators and administrators should investigate their school's barriers preventing families from participating, Hashim said. They should also consider the pandemic's impact on their local community, rather than assume they face the same barriers as what's being reported in national surveys, she said.

Educators can also expand their mindset on what parent engagement looks like. It's not just parents being passive participants at school events, she said.

"In the ideal kind of model of engagement, families are equal collaborators with educators on defining the goals for schools and transforming schools — not only to improve academic outcomes for kids, but lifelong outcomes for kids, from childhood through adulthood. And ultimately, it's not just about improving school performance, it's about making sure that schools are meeting the needs of the community," Hashim said.

Not refining communication and outreach

Schools should not just be communicating with parents about concerns over their student's academics or behavior. Rather, schools should have regular, frequent and ongoing communication with families. This could include, for example, a weekly all-school update about upcoming events, key dates and student accomplishments.

Schools should also conduct ongoing outreach to families, seeking their preferences for engagement. "Ideally, what would happen is that schools would engage families in a more open-ended conversation about how they would like to show up for their kids in education," Hashim said.

Outreach to teachers is another important area of focus, because teachers have valuable input about how best to work with families. They can also share their needs, such as for more training and support in communicating with families, Hashim said.

Failing to give a complete picture of student performance

If there are concerns about academic progress or behaviors, schools should contact individual families regularly — not just at the end of grading periods, the NWEA report said.

Additionally, when sharing assessment data, educators should explain what is being measured, share other data that provides a complete picture of student performance, and use the data to explain student strengths and progress alongside areas for improvement.

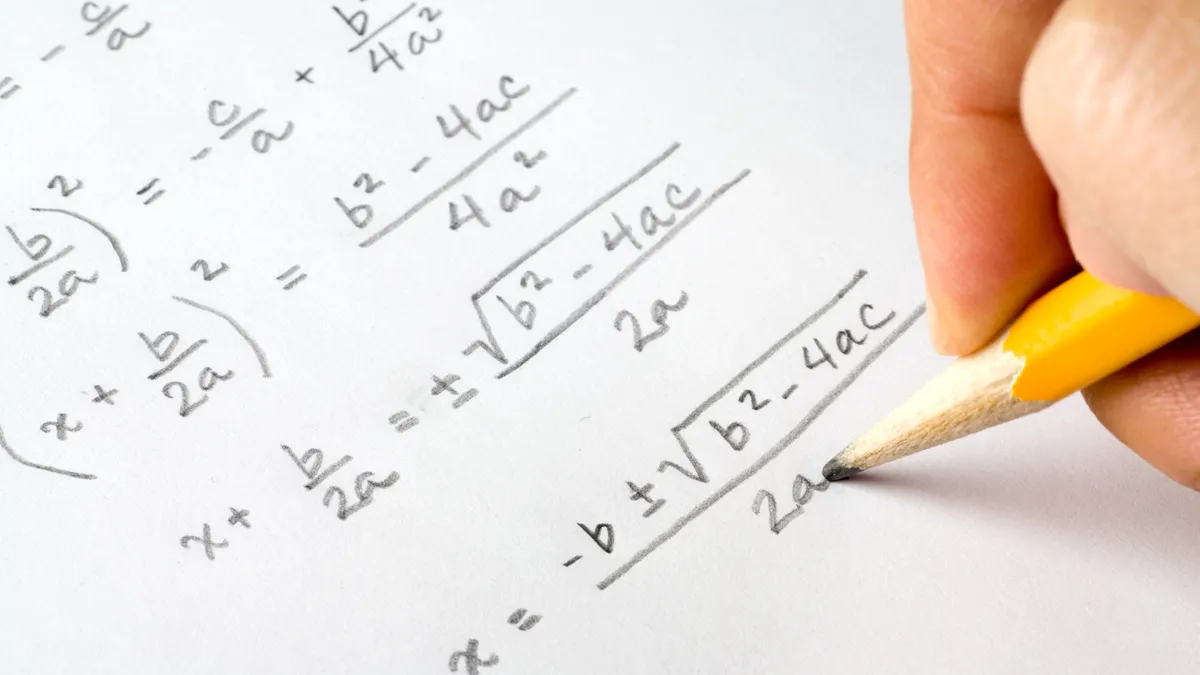

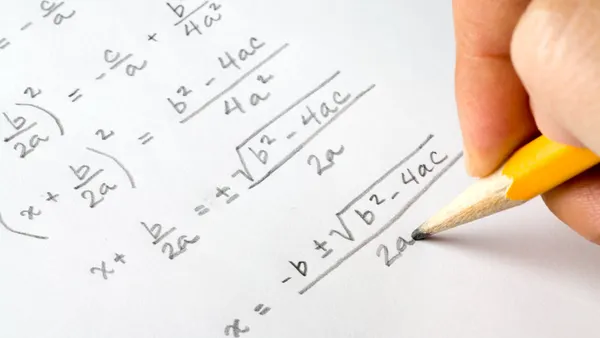

Parents may think, for example, that their child is performing well academically because of "do no harm" grading adjustments, which could include pass-fail policies made during the pandemic to account for unequal impacts on students from school closures.

That disconnect between letter grades — which parents view as the primary indicator of performance — and standardized assessment results can give families a false sense of security that their child is hitting academic targets.

"Parents want more frequent and regular communication with schools so that they can then know how best to show up to support their kids," said Hashim.