Every student with autism is different, but as the number of diagnoses continues to grow and many are included in general education classrooms, teachers and school leaders can implement certain principles to ensure students with autism thrive.

Among the best practices schools can take are direct and multisensory instruction, role-playing and modeling behaviors, employing a variety of communication strategies, and being sensitive to overstimulating situations.

Explicit instruction with step-by-step guidance in carrying out assignments, paired with multiple ways to digest those instructions — spanning visual, auditory and even kinesthetic cues — are the first concepts that come to mind for Delancy Allred, public policy manager at the Autism Society of America.

Students with autism may also benefit from visual supports like schedules, charts and diagrams can be very helpful, such as “if-then” boards for younger children that lay out a scenario in the form of “if this is done, then this will be the result or reward” to provide incentives to finish an assignment or behave well, said Allred.

The portion of students with autism who qualify for services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act increased by nearly 10% between 2022 and 2023, according to a The Advocacy Institute analysis of U.S. Department of Education Department data for students ages 5-21.

A 2025 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 1 in 31 8-year-olds were identified with autism in 2022. That’s up from 1 in 44 in 2018 and 1 in 150 in 2000. Autism is about 4 times more common in boys than girls, the CDC said.

Monica Waltman, president of the South Dakota chapter of the Council of Administrators of Special Education and director of special services at Carrousel School in Box Elder, South Dakota, puts a visually supportive environment high on the list, noting that teachers often talk at students too much and forget that students learn visually, too.

For example, when one teacher expressed frustration to her about a student who came into class, opened his computer and did not listen to directions, Waltman pointed out that the first line on the visual instructions at the front of the classroom read, “Get out your computer and log on.” She persuaded the teacher to change the directions to, “Sit down and listen to instructions.” And the student did so the very next day.

Allred said that role-modeling and practicing real-life scenarios, regardless of academic content, can be very helpful to build students’ social skills and teach them to read social cues. Given that approximately 40% of students with autism don’t communicate in the traditional manner, she adds that teachers need to establish systems ranging from high-tech devices that help students get across their needs and wants to low-tech approaches where students simply point to something.

The growth in tech devices sometimes causes educators to “pathologize students’ quirks,” Waltman said, adding that school is no longer the place to teach technology, because students are "digital natives." “The amount of time kids spend on technology does impede their ability to socially communicate,” especially for students with autism, given their tendency to fixate on preferences, Waltman said.

Teachers also need to take into account students’ sensory needs, Allred said. “Bright lights can be challenging,” she said. “Offer a dimming light, or don’t have overhead lights on. Maybe lamps can be more supportive."

She also recommends educators try to limit background noises or give space in a classroom that can be quieter and offer noise-canceling headphones.

Family collaboration is another key element of working with children on the autism spectrum, Waltman said. That includes open communication to determine how the school day is impacting a student at home to make sure a student isn’t barely keeping composure during the day and then “losing it” at home.

And teachers and school leaders shouldn’t stereotype autism as a “boy thing” and should be mindful that girls on the spectrum are more likely to “mask” their struggles, she said.

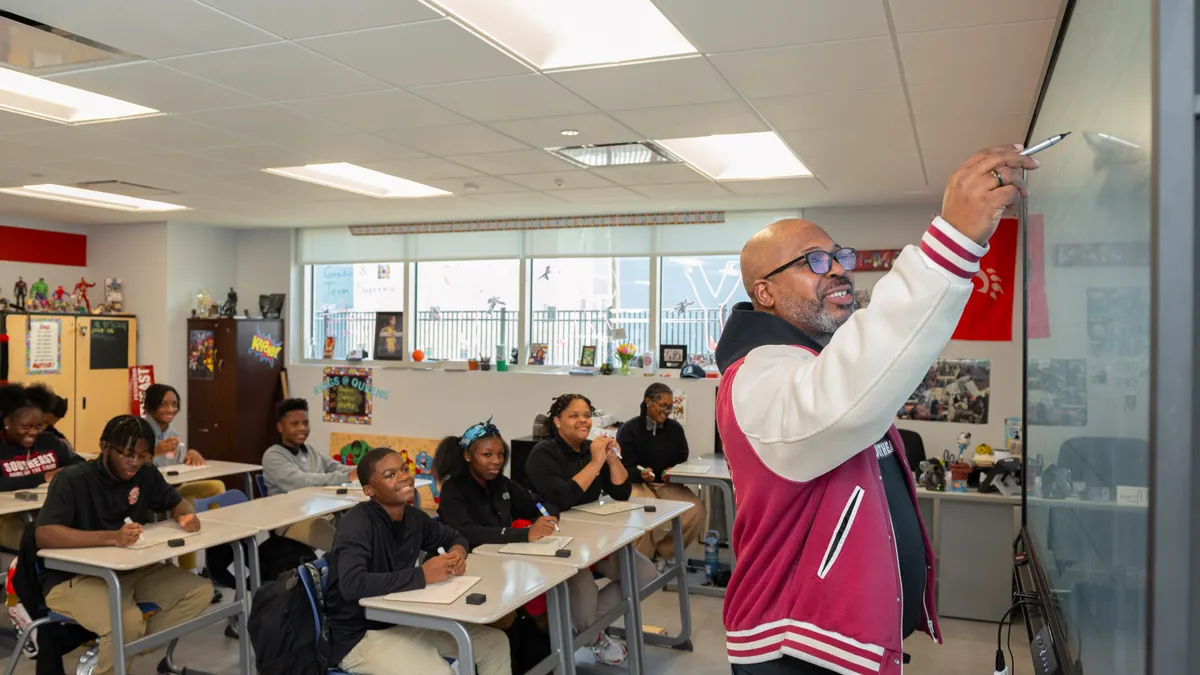

Working with families is critically important, agrees Jamai Leigh, a special education teacher at REACH Academy, a special education-focused school in West Harrison, New York.

“You have to build with parents,” she said. “A lot of parents are either in denial that their student has a disability, or they may not know how to ask the right questions to get those resources.”

Schools need to have a range of learning settings and options for students with autism, including self-contained classrooms and paraprofessionals who can provide 1-to-1 supports, while still ensuring students with autism “feel like they are a part of the school community,” Leigh said. “And challenge them. Don’t think that because they don’t talk or may have some other disability, they’re not capable.”

Students with autism require patience, compassion and genuineness, she said. “Leave everything at the door because they need all of you.”