SEATTLE — In 2024, nearly half — 48% — of Oregon’s 4th graders scored below basic in reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

Not only is that 7 percentage points worse than the national average, but 48% represented a significant jump from pre-pandemic levels in 2019, when 36% of Oregon’s 4th graders tested below basic for reading.

The state's latest reading scores are “disgraceful” and “unacceptable,” said Darcy Soto, director of learning acceleration at Portland Public Schools.

But unlike for the state at large, the Portland district has seen an increase — albeit a slight one of 1% — in reading scores since the pandemic, said Karla Hudson, program administrator for the district’s learning acceleration team. Still, Portland's progress has been slow and incremental, she said, and less than 60% of the district’s students are proficient in reading.

“We have a lot of work to do,” Hudson said, which is why the 43,500-student district has zeroed in on providing high-impact tutoring.

Joined by Stanford University’s Nancy Waymack, Soto and Hudson shared what Portland has learned from its efforts during a July 12 session at UNITED, the National Conference on School Leadership.

High-impact tutoring is a data-driven service that is embedded into the school day and uses consistent, well-supported tutors, said Waymack, director of research, partnerships and policy for Stanford University’s National Student Support Accelerator. The tutors use high-quality instructional materials and hold sessions at least three times a week in small groups of no more than four students, she said.

While teachers can be successful tutors, Waymack said, so too can community members like college students and retirees. Regardless, it’s important that students be able to build a relationship with their tutors, she said.

Data also plays a valuable role in tracking student progress throughout the tutoring, Waymack said. When tutoring occurs during school hours or shortly before or after class time, she said, research shows students are far more likely to attend sessions.

Years in the making

Portland began its early literacy tutoring program through a small after-school pilot initiative in 2021-22 at a few elementary schools for students in grades 3-5, said Soto. The pilot started to show “some really great outcomes,” she said, allowing the district to expand the program from 6 to 20 schools by the 2022-23 school year.

During those first two years, teachers were trained on the curriculum and paid for extended hours to tutor after school and. While that approach did improve students’ reading skills, Soto said, “it was very expensive” given teacher pay and the small student group size. This made the pilot difficult to scale to other schools.

As the tutoring program continued into the 2023-24 school year, the district began shifting to a more cost-effective model — especially as federal pandemic relief funds were sunsetting, Soto said.

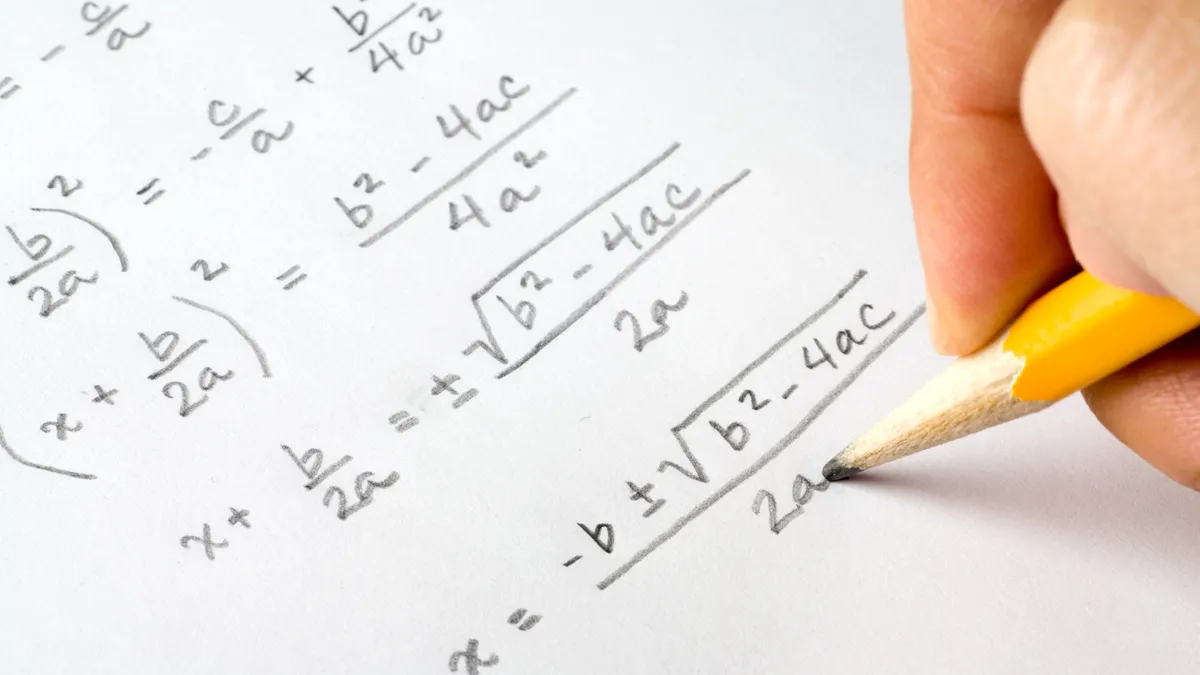

By the 2024-25 school year, Soto said, the district used some of its last remaining Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds to partner with the Oregon Department of Education and Oregon State University to develop a free K-3 tutoring curriculum aligned with structured literacy instruction.

After successfully piloting the new curriculum in summer 2024, the district launched a $1.2 million program across 50 of its 58 elementary schools to serve over 1,200 students in 2024-25, Soto said. The program hired 152 tutors — mostly paraprofessionals — and was embedded during school hours during 30-minute blocks that didn’t interfere with core instruction.

Outcomes and what’s next

Portland attributes recorded a wide range of student outcomes to the tutoring program. One school saw an average growth of 91% on post-tutoring assessments, while another grew on average by just 18%, according to Soto.

The tutoring outcome data so far is "interesting and complex,” Soto said, but it still shows that the program is working.

However, as the district faces declining enrollment and big budget cuts, it has sought partnerships to keep it going, Hudson said. As a result, most tutoring for the 2025-26 school year will run through a community-based partner known as Reading Results with some in-house support and also a new AI literacy tutoring tool.

A majority of the funding will come from the district’s education foundation via a one-year, $1 million grant, Hudson said. The remaining funds will be from the state’s early literacy grant and a private foundation.

When the tutoring program gets underway in the new school year, Soto said her team will continue collecting feedback and data from participants. Sharing success stories, she noted, will help secure funding for the program’s future.

It also will be important to keep adjusting the model’s funding and structure as the district’s budget and capacity shift, Soto said.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards