Sustained, comprehensive investments in school counseling can greatly improve school climate and academic and behavioral outcomes — especially for students in historically underserved areas, according to a recently released study from the University of California, Los Angeles Center for the Transformation of Schools.

The study focused on Livingston Union School District in California’s Central Valley, which serves a rural, predominantly Hispanic and socioeconomically challenged student population. Due to metrics such as below-state-average chronic absenteeism rates, LUSD has been recognized as a “bright spot” by the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence, AttendanceWorks, and the University of California, Davis.

The four-school, transitional kindergarten to 8th grade district’s success is credited to its use of a student-centered, data-driven model based on an American School Counseling Association framework.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the district had a 4.9% chronic absenteeism rate, which spiked to 18.3% in 2023 before falling to 14.2% in spring 2024, and a 1.9% suspension rate, which rose to 3.4% in 2022 before falling to 2.8% in 2023.

Too often, the roles of school counselors have become “over-expanded” to the point where they can’t serve students as well as they could, said Adriana Jaramillo Castillo, research analyst at the UCLA center and lead researcher, who suggests that Livingston USD’s ASCA-based model is one that other districts should consider replicating.

Among the key facets are lowering the student-to-counselor ratio from above 400:1 — the national average — to more like 200:1 or 250:1, which is “more feasible and provides more personal interactions between counselors and students,” she said. “The model also nuances a lot of the roles of the counselor away from administrative tasks,” based on the ASCA’s recommendation that at least 80% of counselors’ time be spent in services provided to students.

School counseling is not required by state law in California, but Livingston Union has been providing it since Alma Lopez, school counselor coordinator, was hired in 2006, Lopez said.

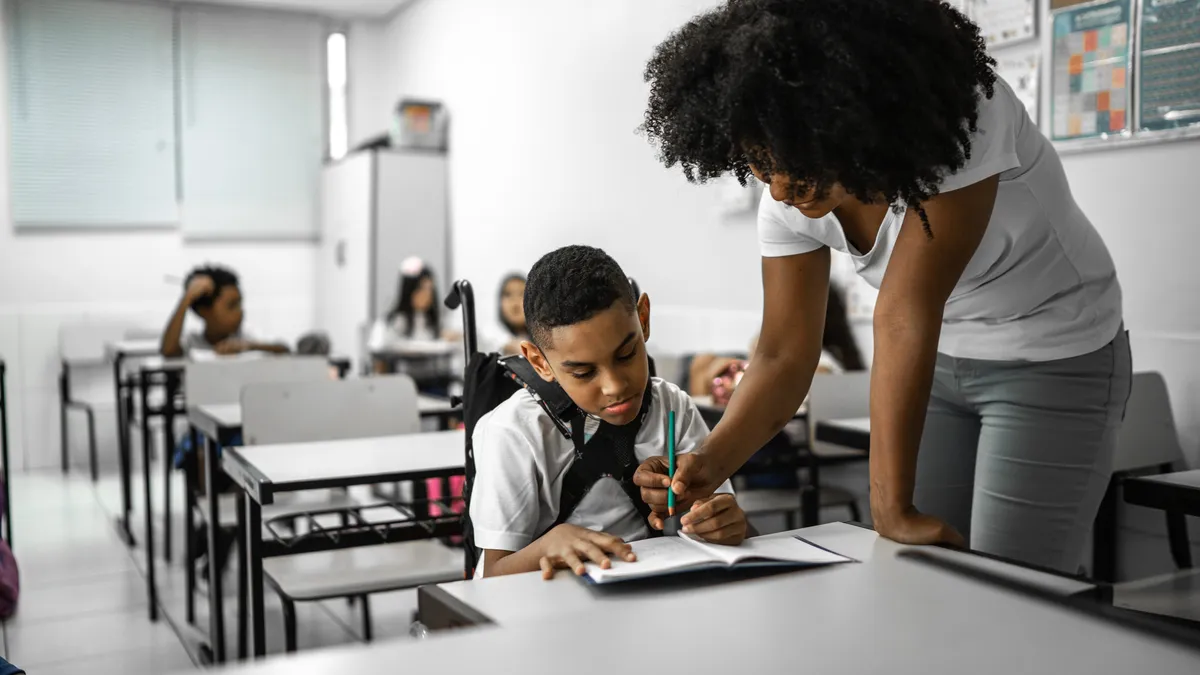

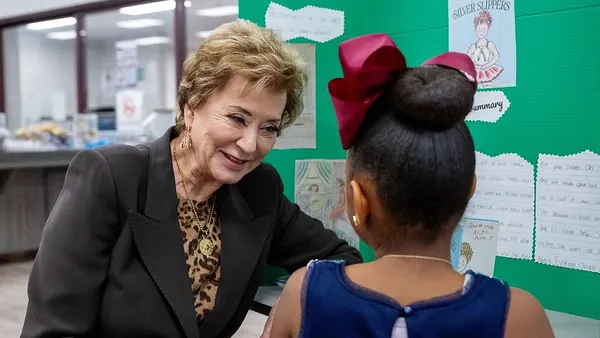

Counselors are “in the classroom leading instruction, in small groups in our office based on what our data says is needed, and with crisis counseling support as needed,” she said. “We have a pretty highly structured program.”

The counseling department meets before the school year to plan its rounds, with counselors visiting each classroom six times per school year: twice to talk about academic achievement and the importance of attending school; twice to cover college and career readiness, sometimes with university partners; and twice to discuss social and emotional topics, Lopez said.

“There’s a high emphasis on that mental health space, understanding that school counselors are part of the mental health team at schools along with psychologists and social workers,” she said. “It is preventative in nature, and proactive.”

School counselors play a key role in both academics and student well-being, particularly in districts with disadvantaged demographics, Castillo said.

“That’s not to say this counseling model would not work in an urban or suburban educational setting,” she said. “Livingston Union was recognized as a bright spot because of all the good work they have been doing, and their expansive knowledge of using data-driven and evidence-based practices.”

When Joseph Bishop co-founded the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools eight years ago and began surveying how need-based funding from the state is operationalized at the local level, Livingston Union kept coming to his attention. Bishop, the center’s executive director, believes stability in leadership of the district — starting with Superintendent Andres Zamora — as well as doubling down on the counseling program have led to the positive results.

“Over time, they made great strides. COVID happened, they took a few steps back, and now they’re turning to where they were,” Bishop said. “They have unapologetically focused on school counseling. And it’s not only that school counseling matters, they’ve rethought placement of school counselors.”

“It’s a small enough community that you can get things done, but they don’t have a lot of resources,” Bishop said, noting that many parents work in the region's fields and factories. “They’re trying to expose students to new possibilities and see themselves as having a productive life. They’re not accepting of how things have been. They’re pushing to do more.”