Jennifer Coco is the interim executive director of The Center for Learner Equity.

The path to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education will have a generational impact — eliminating the safeguards that have ensured all students have access to equitable, inclusive schools since the department’s founding in 1979.

Specifically, the recent threats to consolidate the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights within the U.S. Department of Justice are even more devastating for students at the intersection of race, poverty and disability. This move severs the civil rights lifelines that protect students who are farthest from privilege and opportunity.

OCR, an office within the Education Department, was established to enforce federal civil rights laws in schools. Notably,OCR provides students with access to individual discrimination investigations and upholds their civil rights in schools when wrongdoing has occurred, such as in instances where they are excluded due a disability, or when required accommodations are not provided.

And OCR investigations don’t just demand justice for individual students — they can also direct systemic changes in school policy and practice to ensure further injustice doesn’t happen again to any other student in that community.

As an attorney and advocate for children with disabilities, I’ve spent nearly two decades working to ensure that schools are welcoming places for students and families. One of my first education law experiences was an internship at OCR. I learned from OCR’s experienced education legal experts who deeply understood civil rights law and protecting students' rights.

That experience directed the trajectory of my career and cemented my interest in becoming an education civil rights attorney. The regional office I interned at in Chicago 18 years ago no longer exists; its entire staff was fired by the current administration.

Early in my career as an education civil rights attorney, I also experienced filing a complaint with the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, which led to sweeping districtwide reforms that dramatically improved language access and civil rights protections for multilingual learners and undocumented students. I am an ardent supporter of DOJ’s role in upholding civil rights; my concern about collapsing OCR within the DOJ isn’t out of objection to DOJ’s important role.

What’s getting lost in the conversation is why Congress originally saw fit to have both the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division and the Office for Civil Rights.

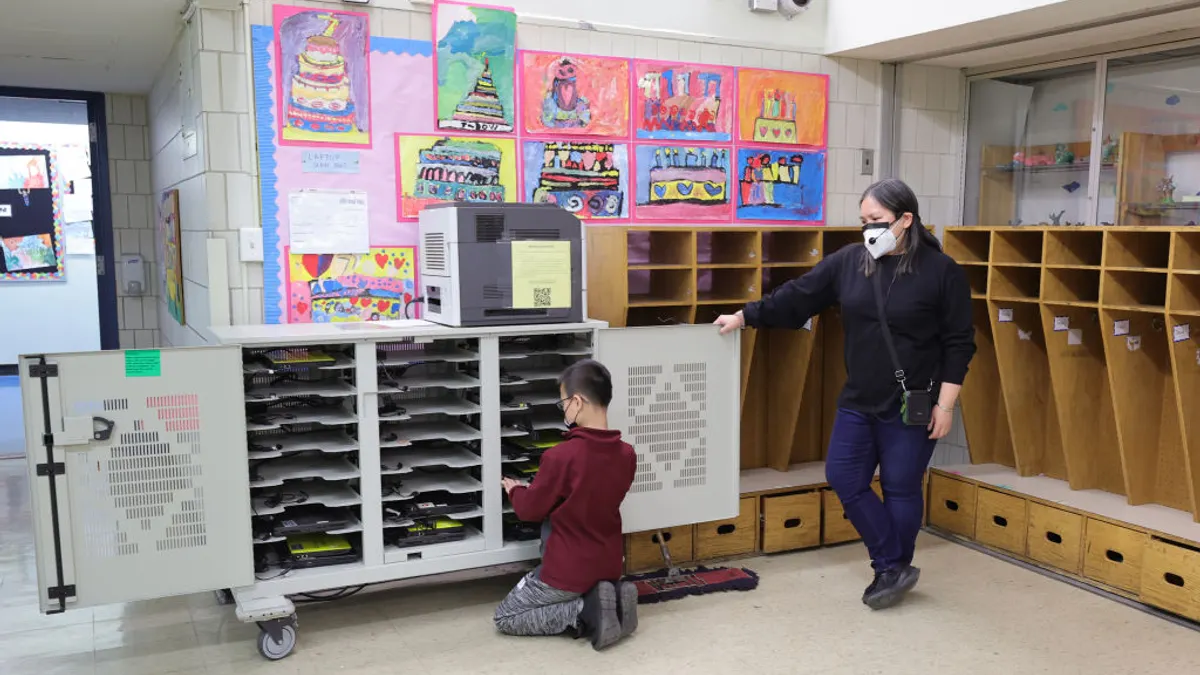

Unlike DOJ, which investigates systemic violations and initiates federal litigation, OCR fields and investigates individual complaints — over 25,000 currently pending, to be exact. OCR is intended to have a strong regional presence, with field offices of attorneys able to investigate and handle a volume of cases in their respective regions. They have a detailed case processing manual with timelines and procedures; every complaint is entitled to a response.

Indeed, most agencies have an Office for Civil Rights — from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to the U.S. Department of Transportation. That’s because the agency-specific context and expertise help protect and uphold our civil rights across the many different functions of our government.

It also belies 50 years of commonly accepted truth: that every facet of our government should be equipped to uphold our civil rights. The volume of demand, with tens of thousands of cases pending, illustrates that the Department of Justice is not resourced nor staffed to shoulder it all. Nor was that the intention.

In addition to investigating discrimination complaints, the Education Department’s OCR is also tasked with collecting and reporting the Civil Rights Data Collection. It is the only nationwide comprehensive look at students’ experiences and access to opportunities, broken down by different identities, including disability.

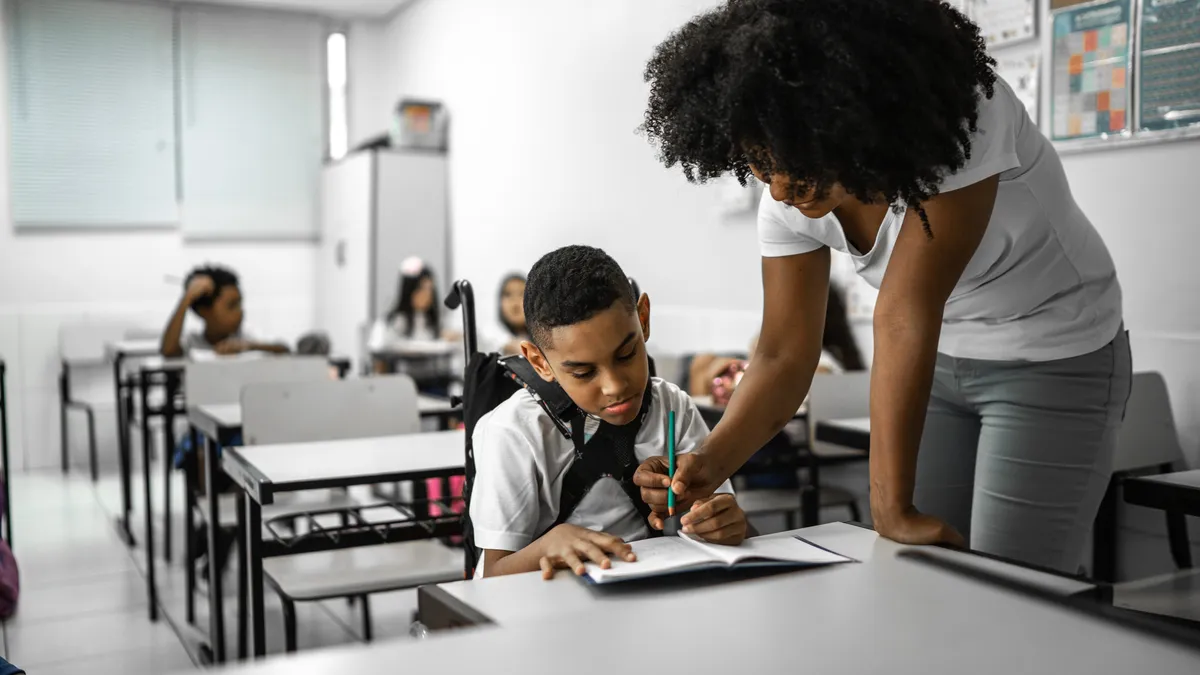

One in seven American public school students is identified as having a disability, according to the Center for Learner Equity’s recent analyses of the CRDC statistics. Such data helps schools and the public understand how students are accessing educational opportunities or experiencing barriers, based on their race, gender, disability or other criteria.

Without this data, we lose vital transparency about students’ access to equity and opportunity. Without OCR, it’s unclear who administers CRDC or collects its massive dataset from every public school in the country.

The most recent OCR Annual Report showed that 37% of its 22,687 complaints were from students with disabilities alleging discrimination at schools.

This administration has responded to the magnitude of children seeking justice by consolidating and eliminating the staff responsible for upholding the rights of the 14% of students in public schools who are identified as having a disability. And the DOJ does not have the capacity to effectively pursue complaints regarding discrimination of students with disabilities in K-12 schools.

Most would agree we cannot maintain the status quo for our students; but losing both OCR’s personnel as well as their insights reverses 50 years of progress. Gutting a federal agency tasked with overseeing civil rights enforcement is not the solution. Rather, it reverts us to a time when all children did not have access to justice — and it abandons the nearly 25,000 students awaiting that justice today.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards