Though data is still forthcoming, anecdotal evidence suggests the return to in-person learning may be coupled with a spike in bullying incidents.

The most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey revealed 25% of teens nationwide reported being bullied. CDC is continuing to gather data for 2021, which won’t be available until 2023, said Melissa Mercado-Crespo, lead behavioral scientist in youth violence and emerging topics, in an email.

The agency is also looking into the ways COVID-19 has changed attendance in schools and how that has impacted bullying behaviors, Mercado-Crespo said.

Meanwhile, the return of students to physical classrooms after a year of remote learning due to COVID-19 has led to fears of a sharp increase in school bullying numbers, said Amanda Nickerson, director of the Alberti Center for Bullying Abuse Prevention at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

Michele Borba, a bullying prevention expert and former teacher, said in her experiences interacting with school counselors this year, she’s seen a return — and even a possible surge — in bullying.

Mask bullying more prevalent in schools without mandates

There have been fears of mask bullying in school districts without universal face-covering policies, but the CDC currently has no data to put context to these concerns.

Borba said she's heard of cases of mask bullying in districts that do not universally require them. In these cases, Borba and school officials she consults with developed assertive comeback lines for students to use. Students targeted for wearing a face mask can, for instance, respond that they're just looking out for their own and other students' health, she said.

Though it isn’t required, the CDC recommends universal indoor masking in K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status.

“It’s so much easier if everybody has the same policy,” Borba said. “Otherwise you’re pitting one kid against another kid.”

Nickerson agrees. “When you leave it up to the individuals more, and the parents, then I think that’s going to make it more ripe for the conflict and the targeting to happen because it’s then much more obvious about what your beliefs are,” she said.

Borba recommends placing boxes with locks and keys around schools where students can anonymously share reports of bullying. It’s important for students to see teachers and administrators checking and reading reports from the boxes, so their peers know bullying behaviors are monitored, she said. In addition, she recommends schools provide anonymous online reporting options for both students and parents.

Borba also said younger students are showing more signs of aggressive, irritable behavior recently. This trend of fighting, pushing and aggression is tied to growing stress levels among children who have not developed coping skills during the pandemic, she said.

To address this problem, some schools have established a “calm corner” where children can decompress when they feel signs of stress. Teachers can also work with students for a month to help them identify their own stressors and make a personal plan when they feel overwhelmed, Borba said.

Politics coming into schools

Stephen Paterson, principal at Kearsarge Regional Middle School in New Hampshire, noticed an uptick in bullying over gender identity and sexual orientation this fall in his rural 425-student school. Specifically, there have been bullying issues tied to transgender students using the bathroom of their choice, he said.

“Politics come into schools,” he said. “Some of the conversations we’re having around gender issues, bathrooms, that you hear out in the adult world, kids are bringing into schools. It’s resulted in a number of bullying issues and some ongoing conversations.”

Because of this, Paterson has had more one-on-one conversations with parents about the matter. It’s important to build back these relationships with parents who have not seen school officials in person for a long time due to the pandemic, he said.

“So far, it’s gone pretty well. I think that’s where building understanding between the school and home is so important,” Paterson said.

"Go and ask yourself who are your marginalized kids, and make sure that they know they have safe places to go or safe people to contact."

Michele Borba

bullying prevention expert

Borba noted hate speech and targeting students based on race and income level are increasingly becoming a problem.

To find vulnerable students in need of help, Borba suggests teachers ask students to provide them the name of someone they feel safe to contact in any situation. If a student doesn’t provide a name, that’s a problem that should be addressed by creating a sense of belonging and establishing better connections with students, she said.

“Go and ask yourself who are your marginalized kids, and make sure that they know they have safe places to go or safe people to contact,” Borba said.

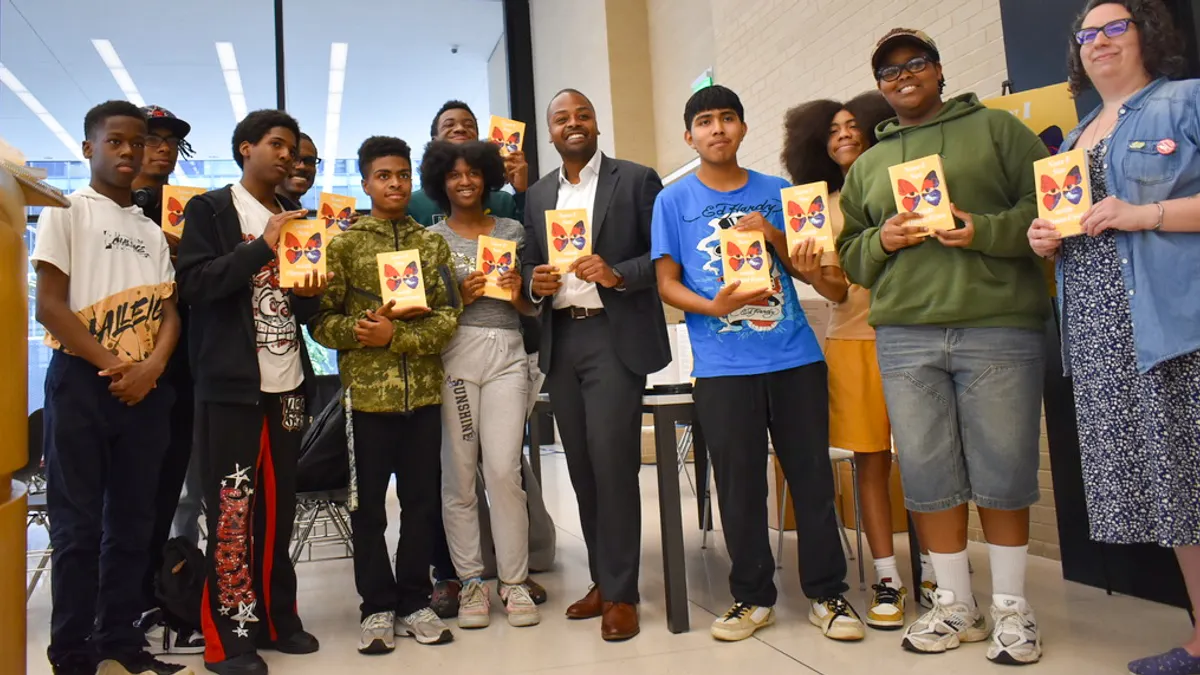

Creating explicitly inclusive environments is important, but cannot be solved by major new school board policies alone, Borba said. For example, a districtwide equity policy is not as effective as diversity or equity clubs run by students, she said.

Prevention strategies are most effective when the policy can “get into the hearts and minds of kids,” Borba added.

In-person aggression on the rise

Even though the latest data is not yet available, a recent study by Annenberg Institute at Brown University suggested school bullying and cyberbullying dropped around 30-40% after schools transitioned to remote learning in spring 2020 and for the 2020-21 school year.

Nickerson said she knows bullying has increased since a majority of students returned to the classroom this fall. “There’s just more opportunity,” Nickerson said. “Because there was that decrease from previous levels, we can expect it to go back up.”

Nickerson said she’s heard reports from many people working in schools that peer conflict and fighting intentions are more apparent.

“I think that adjustment is definitely taking its toll and that people in the schools are seeing that,” she said. These developing problems are related to an overall need for more mental health resources. There’s also recognition by schools for the need to provide social-emotional programs, Nickerson said.

Yet school resources have already been stretched thin because of COVID-19, Nickerson said, making it difficult to revive bullying prevention efforts as needs continue to increase.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards