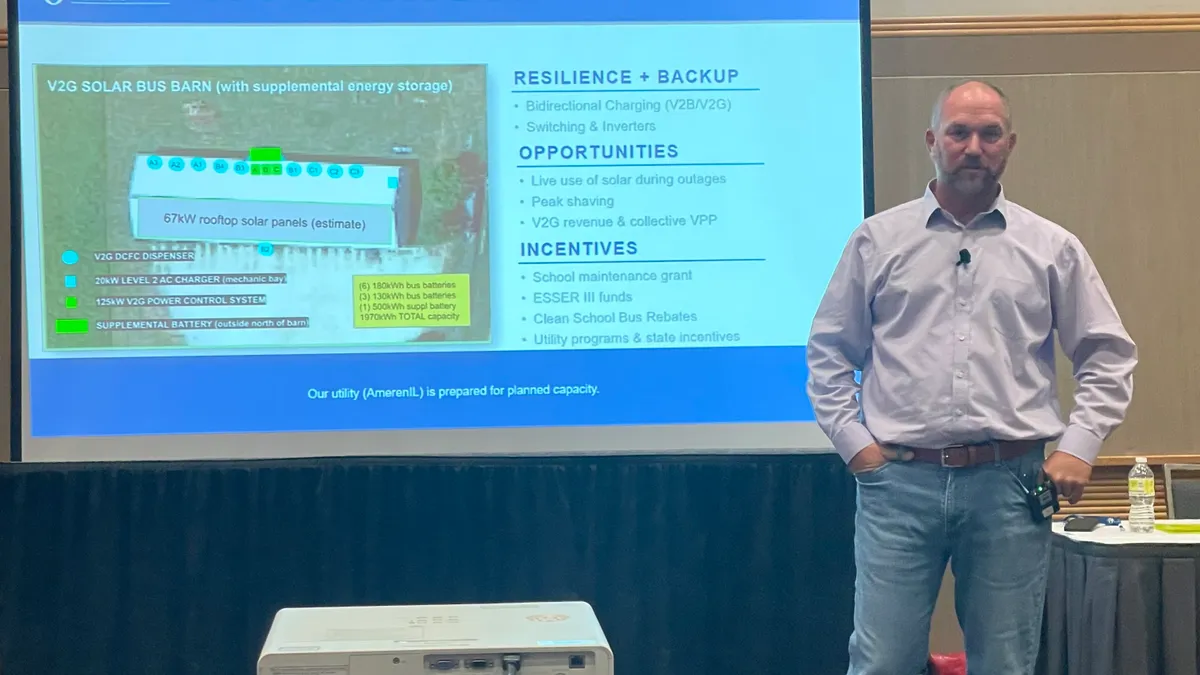

PORTLAND, Ore. — At Williamsfield Community Unit School District No. 210, a small rural district in Illinois, efforts are underway to completely transition all six school buses to run entirely on electricity powered by solar panels located on the school system’s sole campus.

Tim Farquer, the district’s superintendent, spoke Thursday at the Association of School Business Officials International’s Annual Conference & Expo in Portland, Oregon, about how Williamsfield Schools is working to reach this goal by FY 2024.

The push for districts to electrify school buses has grown since Congress passed the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in 2021, which allocated $5 billion to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean School Bus program. The funding will allow districts to replace existing school buses with zero- or low-emission models between fiscal years 2022 and 2026.

The EPA recently closed applications for districts to get part of the $500 million currently available for a clean school bus rebate. Farquer said he applied, and he thinks there’s a 50/50 chance for districts that did so to receive funding during this first round.

Solar energy is gaining steam in other districts, too. This year, nearly 1 in 10 U.S. schools has solar power, according to a recent study by nonprofit Generation180.

The idea to establish a community microgrid on Williamsfield’s 296-student campus powered by solar initially came from "a STEM team" of high school students in 2014.

Students presented the plan to establish a solar array — a group of ground or roof solar panels — to the community. The group later went to Chicago in 2019 for a state lottery to receive funding for renewable energy credits that paid for this portion of the district’s microgrid project, Farquer said.

In 2021, the district also received a school maintenance grant to further fund these efforts.

By 2020, the district installed a ground-mount solar array as well as four roof solar panels on a school building. Most recently, the district entered into a power purchase agreement in August with a third party developer, which installs, owns and operates a solar energy roof mount on the school’s property.

Future-proofing the infrastructure

When planning a microgrid or electrifying a school bus fleet, Farquer said, it’s important that district leaders future-proof their plans.

In Farquer’s case, his district planned to develop enough utility capacity with the generated solar energy to eventually charge up to six school buses, even though all those electric buses don’t exist yet.

“The last thing you want to do is get all these beautiful buses in August, and the chargers are there and they’re hooked up, and you can’t charge your buses as quickly as what you need to, because the infrastructure doesn’t support it,” Farquer said.

While the upfront costs to transition to an electric-run bus model can be expensive for districts, the federal infrastructure bill can help ease those one-time costs, said discussion moderator Thomas Orberger, E-mobility segment head at Siemens, a global company that is one of the largest producers of energy-efficient technologies.

An electric school bus can cost three to four times the price of a traditional diesel-run bus, according to the NYC Clean School Bus Initiative.

Benefits now and later

Since solar arrays began powering school buildings, Williamsfield Schools has saved 26% in energy costs, Farquer said. Once the electric school bus fleet is hopefully implemented by FY 2024, he said, the district is set to save 67% in energy and fuel costs, because it won’t be paying for diesel to power the buses.

“The more money we can take out of our transportation and O&M [Operations and Maintenance] budgets and put into our ed fund, the more we can do for kids,” Farquer said.

On top of that, reducing fuel emissions is an important way to be part of the solution for addressing climate change, he said. The district has also placed electric vehicle charging stations in both staff and student parking lots, which Farquer said can be an incentive for staff recruiting.

Overall, if a small rural district in Illinois with fewer resources can make this switch to renewable energy, he said, so can other districts.

“If we can do it, anybody can,” Farquer said.

Dive Awards

Dive Awards