Can you feed a bear an apple? That’s what Carmalita Seitz, managing director of online learning and digital innovation at ISTE+ASCD thought she was watching a person do in a social media video. But upon closer examination and thinking critically, it became clear to her that artificial intelligence probably played a role.

The episode reminded Seitz of the principles ISTE+ASCD and other organizations put forth with regard to teaching “AI literacy” for school-aged children as early as possible. These guidelines ensure they know what to look and listen for, to think critically, and to use tools like reverse image search to spot “deepfakes” and other AI-generated virtual reality.

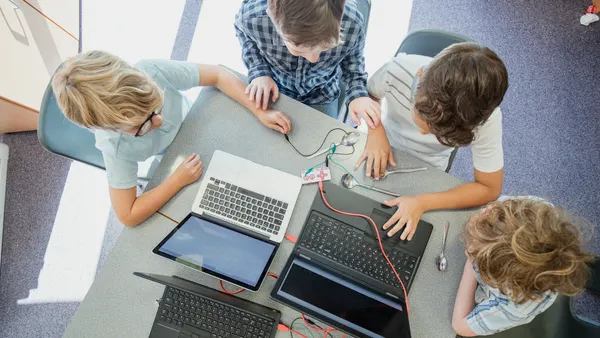

“Digital literacy elements and teaching should start at the same time students are on any digital platforms," which could be kindergarten or higher elementary grades, Seitz said. “There’s many ways for educators to support younger students. … It can be something as simple as saying, ‘Not everything we see online is real.’”

Robbie Torney, senior director of AI programs at Common Sense Media, agrees that AI-generated images and videos have become increasingly realistic, making the topic all the more relevant in the classroom.

“As a greater proportion of AI-generated video is mixed into news feeds, social needs and other places that kids are exposed to, it makes it hard to trust that anything, indeed, is real. And that makes the skills to pause, stop, reflect on where the information is coming from, and think critically all the more important,” he said.

Torney said these conversations should start as soon as students are conducting online research. “Elementary school is a great place to start conversations about what is real information and what’s not,” he said. “As kids get a little older and understand the difference between fact and fiction a little more, it’s a good time to have the conversations about how to verify information.”

But Seitz cautions that waiting until students are old enough to have access to social media independently — generally around age 13 — is probably too late.

“They don’t have to be conversations specifically about tools, but recognizing when something could be fake or real,” she said, adding that digital and AI literacy should not be taught as a separate unit but infused throughout the curricula like reading and writing.

Torney sees a wide array of opportunities to have such conversations. Whether writing a report about frogs or doing a biographical study, “any sort of research exercise where you’re gathering facts from books or the internet, are great places to have conversations. And parents can help lead those conversations.”

Where should AI professional development focus?

In an age when content is designed to grab attention and keep us engaged, it’s crucial that students learn how to engage, Torney said. Common Sense Media suggests a core set of questions:

- Who made this content?

- Why did they make it?

- Do they seem trustworthy? Why or why not?

- Who is the audience for the content that’s being created?

- Is this actual news, or is this an advertisement — and how can you tell?

- Who might benefit from or be harmed by this message?

Administrators need to debunk the fear of AI for their educators through professional development and setting standards to ensure that adults are modeling best practices, Seitz said.

“A lot of times, our fear makes us not do something, to the detriment of students who need to know these skills,” she said. And administrators need to put aside the time to go through the same professional development as teachers, which strengthens the modeling aspect and helps dissipate the fear.

At times it might make sense for students to participate in or even lead the professional development discussions around AI, Seitz said. “They’re in it,” she said. “Whether we want to admit it or not, children are exploring these different digital media.”

ISTE+ASCD’s Digital Citizenship Competencies provide a common set of frameworks, Seitz said, and many states have their own technology standards that provide ideas on how to — and how not to — infuse AI into the classroom. Getting on the same page about vocabulary and definitions is part of building policies and the overall culture, she said.